Boundary Risk

Part Of

Attendant To Practices

- Analysis: Well-defined analysis can create rigid boundaries that limit flexibility.

- Contracts: Contracts can create rigid boundaries that limit flexibility.

- Design: Design decisions can create boundaries that limit flexibility and adaptability.

- Runtime Adoption: Limits flexibility by adhering to specific standards and libraries which may be hard to change later.

- Stakeholder Management: Managing diverse stakeholder expectations can create rigid boundaries.

- Terms Of Reference: Poorly defined terms can create rigid boundaries that limit flexibility.

- Tool Adoption: Once tools become embedded in the process, they can be hard to change.

In the previous sections on Dependency Risk we've touched on Boundary Risk several times, but now it's time to tackle it head-on and discuss this important type of risk.

As shown in the above diagram, Boundary Risk is the risk we face due to commitments around dependencies and the limitations they place on our ability to change. To illustrate, lets consider two examples:

- Although I eat cereals for breakfast, I don't have Boundary Risk on them. If the supermarket runs out of cereals when I go, I can just buy some other food and eat that.

- However the hot water system in my house uses gas. If that's not available I can't just switch to using oil or solar without cost. There is Boundary Risk, but it's low because the supply of gas is plentiful and seems like it will stay that way.

In terms of the Risk Landscape, Boundary Risk is exactly as it says: a boundary, wall or other kind of obstacle in your way to making a move you want to make. This changes the nature of the Risk Landscape, and introduces a maze-like component to it. It also means that we have to make commitments about which way to go, knowing that our future paths are constrained by the decisions we make.

As we discussed in Complexity Risk, there is always the chance we end up at a Dead End, having done work that we need to throw away. In this case, we'll have to head back and make a different decision.

In Software Development

In software development, although we might face Boundary Risk choosing staff or offices, most of the everyday dependency commitments we have to make are around abstractions.

As discussed in Software Dependency Risk, if we are going to use a software tool as a dependency, we have to accept the complexity of its protocols. You have to use its protocol: it won't come to you.

Let's take a look at a hypothetical system structure, in the diagram above. In this design, we are transforming data from the input to the output. But how should we do it?

- We could transform via library 'a', using the Protocols of 'a', and having a dependency on 'a'.

- We could use library 'b', using the Protocols of 'b', and having a dependency on 'b'.

- We could use neither, and avoid the dependency, but potentially pick up lots more Codebase Risk and Schedule Risk because we have to code our own alternative to 'a' and 'b'.

The choice of approach presents us with Boundary Risk because we don't know that we'll necessarily be successful with any of these options until we go down the path of committing to one:

- Maybe 'a' has some undocumented drawbacks that are going to hold us up.

- Maybe 'b' works on some streaming API basis, that is incompatible with the input protocol.

- Maybe 'a' runs on Windows, whereas our code runs on Linux

... and so on.

This is a toy example, but in real life this dilemma occurs when we choose between database vendors, cloud hosting platforms, operating systems, software libraries etc. and it was a big factor in our analysis of Software Dependency Risk.

Factors In Boundary Risk

The degree of Boundary Risk is dependent on a number of factors:

- The Sunk Cost of the Learning Curve we've overcome to integrate the dependency, which may fail to live up to expectations (cf. Feature Fit Risks). We can avoid accreting this by choosing the simplest and fewest dependencies for any task, and trying to Meet Reality quickly.

- Life Expectancy: libraries and products come and go. A choice that was popular when it was made may be superseded in the future by something better. (cf. Market Risk). This may not be a problem until you try to renew a support contract, or try to do an operating system update. Although no-one can predict how long a technology will last, The Lindy Effect suggests that future life expectancy is proportional to current age. So, you might expect a technology that has been around for ten years to be around for a further ten.

- The level of Lock In, where the cost of switching to a new dependency in the future is some function of the level of commitment to the current dependency. As an example, consider the level of commitment you have to your mother tongue. If you have spent your entire life committed to learning and communicating in English, there is a massive level of lock-in. Overcoming this to become fluent in Chinese may be an overwhelming task.

- Future needs: will the dependency satisfy your expanding requirements going forward? (cf. Feature Drift Risk)

- Ownership changes: Microsoft buys GitHub. What will happen to the ecosystem around GitHub now?

- Licensing changes: (e.g. Oracle buys Tangosol who make Coherence for example). Having done this, they increase the licensing costs of Coherence to huge levels, milking the Cash Cow of the installed user-base, but ensuring no-one else is likely to commit to it in the future.

Ecosystems and Lock-In

Sometimes, one choice leads to another, and you're forced to "double down" on your original choice, and head further down the path of commitment.

On the face of it, WordPress and Drupal should be very similar:

- They are both Content Management Systems.

- They both use a LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySql, PHP) Stack.

- They were both started around the same time (2001 for Drupal, 2003 for WordPress).

- They are both Open-Source, and have a wide variety of plugins, that is, ways for other programmers to extend the functionality in new directions.

But crucially, the underlying abstractions of WordPress and Drupal are different, so the plugins available for each are different. The quality and choice of plugins for a given platform, along with factors such as community and online documentation, is often called its ecosystem:

"... a set of businesses functioning as a unit and interacting with a shared market for software and services, together with relationships among them. These relationships are frequently underpinned by a common technological platform and operate through the exchange of information, resources, and artifacts." - Software Ecosystem, Wikipedia

You can think of the ecosystem as being like the footprint of a town or a city, consisting of the buildings, transport network and the people that live there. Within the city, and because of the transport network and the amenities available, it's easy to make rapid, useful moves on the Risk Landscape. In a software ecosystem it's the same: the ecosystem has gathered together to provide a way to mitigate various different Feature Risks in a common way.

Ecosystem size is one key determinant of Boundary Risk:

- A large ecosystem has a large boundary circumference. Boundary Risk is lower in a large ecosystem because your moves on the Risk Landscape are unlikely to collide with it. The boundary got large because other developers before you hit the boundary and did the work building the software equivalents of bridges and roads and pushing it back so that the boundary didn't get in their way.

- In a small ecosystem, you are much more likely to come into contact with the edges of the boundary. You will have to be the developer that pushes back the frontier and builds the roads for the others. This is hard work.

Big Ecosystems Get Bigger

In the real world, there is a tendency for big cities to get bigger. The more people that live there, the more services they provide and need, and therefore, the more immigrants they attract. It's the same in the software world too. In both cases, this is due to the Network Effect:

"... the positive effect described in economics and business that an additional user of a good or service has on the value of that product to others. When a network effect is present, the value of a product or service increases according to the number of others using it." - Network Effect, Wikipedia

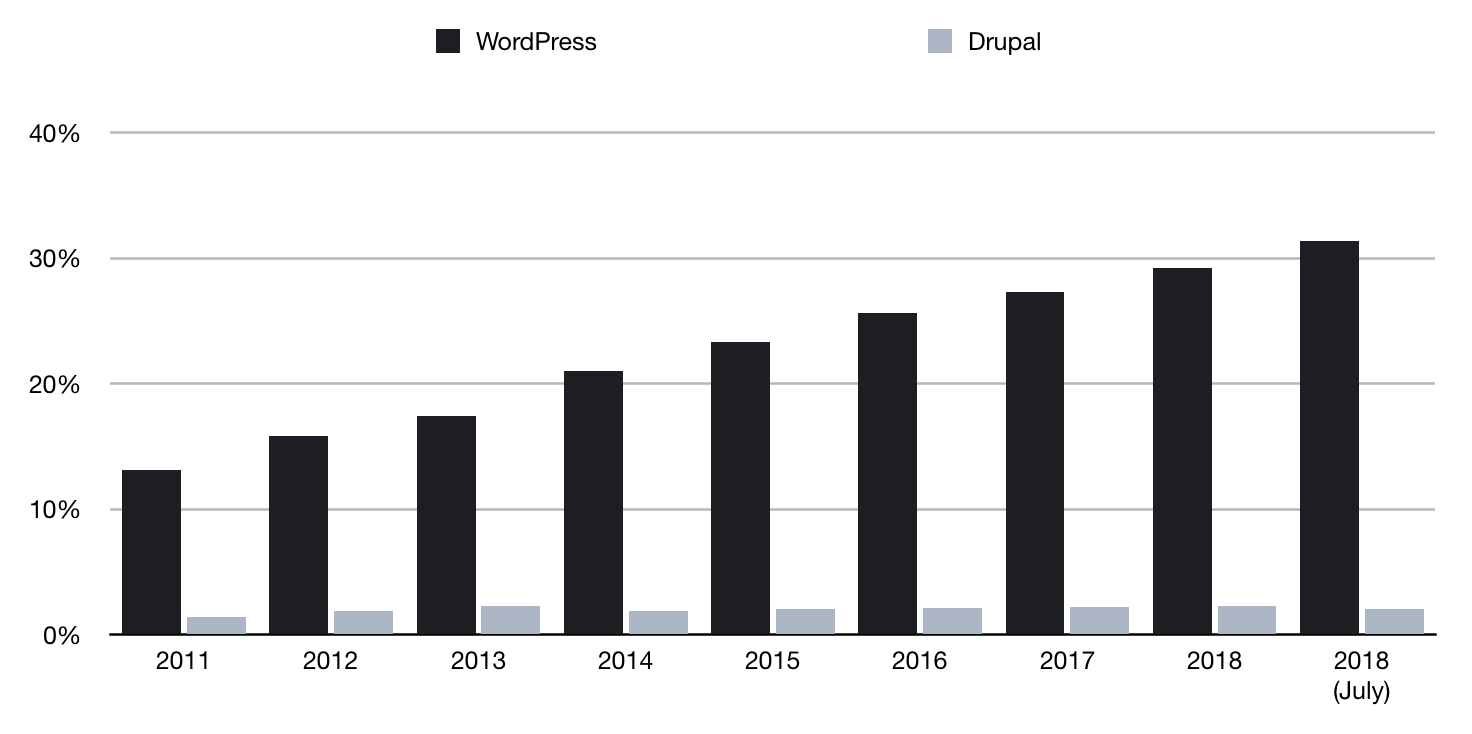

You can see the same effect in the software ecosystems with the adoption rates of WordPress and Drupal, shown in the chart above. Note: this is over all sites on the internet, so Drupal accounts for hundreds of thousands of sites. In 2018, WordPress is approximately 32% of all web-sites. For Drupal it's 2%.

Did WordPress gain this march because it was always better than Drupal? That's arguable. Certainly, they're not different enough that WordPress is 16x better. That it's this way round could be entirely accidental, and a result of Network Effect.

But, by now, if they are to be compared side-by-side, WordPress might be better due to the sheer number of people in this ecosystem who are...

- Creating web sites.

- Using those sites.

- Submitting bug requests.

- Fixing bugs.

- Writing documentation.

- Building plugins.

- Creating features.

- Improving the core platform.

But is bigger always better? Perhaps not.

Big Ecosystems Are More Complex

When a tool or platform is popular, it is under pressure to increase in complexity. This is because people are attracted to something useful and want to extend it to new purposes. This is known as The Peter Principle:

"The Peter principle is a concept in management developed by Laurence J. Peter, which observes that people in a hierarchy tend to rise to their 'level of incompetence'." - The Peter Principle, Wikipedia

Although designed for people, it can just as easily be applied to any other dependency you can think of. This means when things get popular, there is a tendency towards Conceptual Integrity Risk and Complexity Risk.

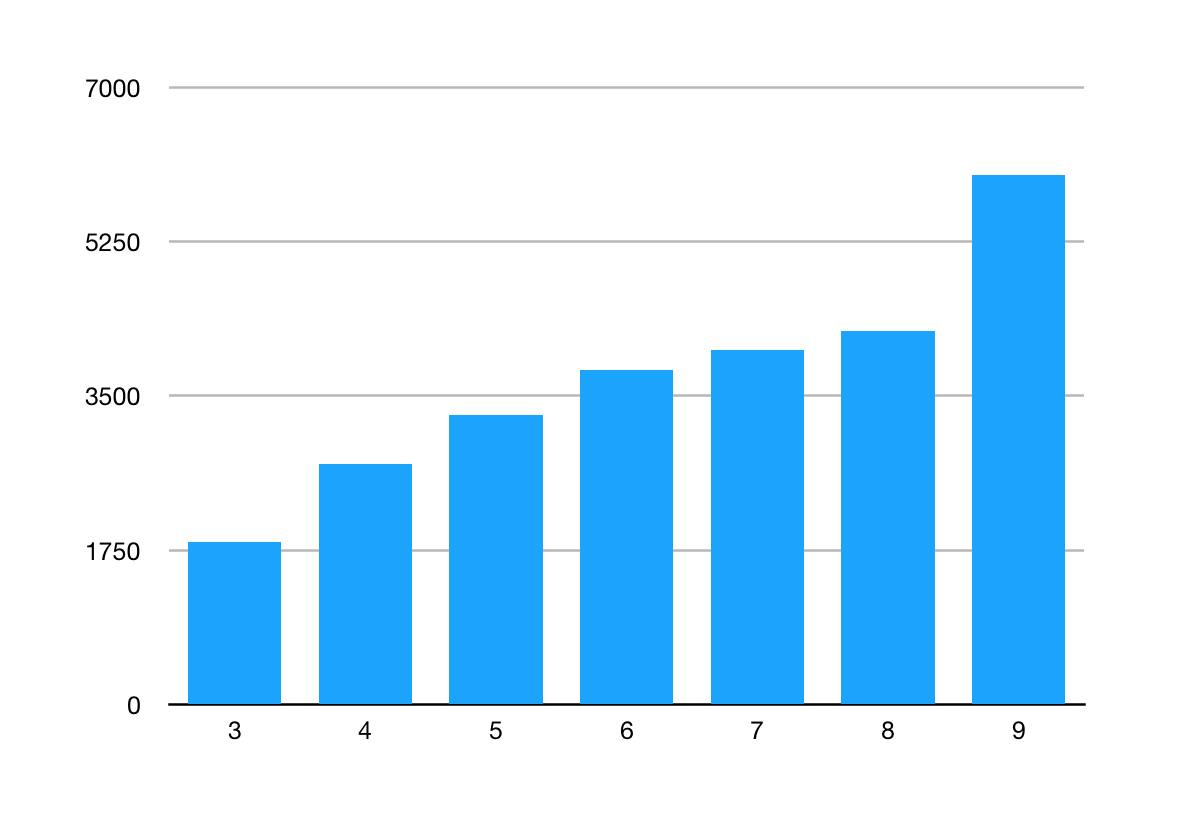

The above chart is an example of this: look at how the number of public classes in Java (a good proxy for the boundary) has increased with each release.

Backward Compatibility

As we saw in Software Dependency Risk, The art of good design is to afford the greatest increase in functionality with the smallest increase in complexity possible, and this usually means Refactoring. But, this is at odds with Backward Compatibility.

Each new version has a greater functional scope than the one before (pushing back Boundary Risk), making the platform more attractive to build solutions in. But this increases the Complexity Risk as there is more functionality to deal with.

You can see in the diagram above the Peter Principle at play: as more responsibility is given to a dependency, the more complex it gets and the greater the learning curve to work with it. Large ecosystems like Java react to Learning Curve Risk by having copious amounts of literature to read or buy to help, but it is still off-putting.

Because Complexity is Mass, large ecosystems can't respond quickly to Feature Drift. This means that when the world changes, new ecosystems are likely to appear to fill gaps, rather than old ones moving in.

Managing Boundary Risk

Let's look at two ways in which we can manage Boundary Risk: bridges and standards.

Ecosystem Bridges

Sometimes, technology comes along that allows us to cross boundaries, like a bridge or a road. This has the effect of making it easy to to go from one self-contained ecosystem to another. Going back to WordPress, a simple example might be the Analytics Dashboard which provides Google Analytics functionality inside WordPress.

I find, a lot of code I write is of this nature: trying to write the glue code to join together two different ecosystems.

As shown in the above diagram, mitigating Boundary Risk involves taking on complexity. The more Protocol Complexity there is on either side of the two ecosystems, the more complex the bridge will necessarily be. The below table shows some examples of this.

| Protocol Risk From A | Protocol Risk From B | Resulting Bridge Complexity | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low | Simple | Changing from one date format to another. |

| High | Low | Moderate | Status Dashboard. |

| High | High | Complex | Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) Tools. |

From examining the Protocol Risk at each end of the bridge you are creating, you can get a rough idea of how complex the endeavour will be:

- If it's low-risk at both ends, you're probably going to be able to knock it out easily. Like translating a date, or converting one file format to another.

- Where one of the protocols is evolving, you're definitely going to need to keep releasing new versions. The functionality of a

Calculatorapp on my phone remains the same, but new versions have to be released as the phone APIs change, screens change resolution and so on.

Standards

Standards mitigate Boundary Risk in one of two ways:

- Abstract over the ecosystems. Provide a standard protocol (a lingua franca) which can be converted down into the protocol of any of a number of competing ecosystems.

-

The C programming language provided a way to get the same programs compiled against different CPU instruction sets, therefore providing some portability to code.

-

Java took what C did and went one step further, providing interoperability at the library level. Java code could run anywhere where Java was installed.

- Force adoption. All of the ecosystems start using the standard for fear of being left out in the cold. Sometimes, a standards body is involved, but other times a "de facto" standard emerges that everyone adopts.

-

ASCII: fixed the different-character-sets Boundary Risk by being a standard that others could adopt. Before everyone agreed on ASCII, copying data from one computer system to another was a massive pain, and would involve some kind of translation. Unicode continues this work.

-

Internet Protocol. As we saw in Communication Risk, the Internet Protocol (IP) is the lingua franca of the modern Internet. However, at one period of time, there were many competing standards. IP was the ecosystem that "won", and was subsequently standardised by the IETF. This is actually an example of both approaches: as we saw in Communication Risk, Internet Protocol is also an abstraction over lower-level protocols.

Boundary Risk Cycle

Boundary Risk seems to progress in cycles. As a piece of technology becomes more mature, there are more standards and bridges, and Boundary Risk is lower. Once Boundary Risk is low and a particular approach is proven, there will be innovation upon this, giving rise to new opportunities for Boundary Risk (see the diagram above). Here are some examples:

-

Processor Chips. By providing features (instructions) on their processors that other vendors didn't have, manufacturers made their processors more attractive to system integrators. However, since the instructions were different on different chips, this created Boundary Risk for the integrators. Intel and Microsoft were able to use this fact to build a big ecosystem around Windows running on Intel chips (so called, WinTel). The Intel instruction set is nowadays a de-facto standard for PCs.

-

Browsers. In the late 1990s, faced with the emergence of the nascent World Wide Web, and the Netscape Navigator browser, Microsoft adopted a strategy known as Embrace and Extend. The idea of this was to subvert the HTML standard to their own ends by embracing the standard and creating their own browser Internet Explorer and then extending it with as much functionality as possible, which would then not work in Netscape Navigator. They then embarked on a campaign to try and get everyone to "upgrade" to Internet Explorer. In this way, they hoped to "own" the Internet, or at least, the software of the browser, which they saw as analogous to being the "operating system" of the Internet, and therefore a threat to their own operating system, Windows.

-

Mobile Operating Systems. We currently have just two main mobile ecosystems (although there used to be many more): Apple's iOS and Google's Android, which are both very different and complex ecosystems with large, complex boundaries. They are both innovating as fast as possible to keep users happy with their features. Bridging tools like Xamarin exist which allow you to build applications sharing code over both platforms.

-

Cloud Computing. Amazon Web Services (AWS) are competing with Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud Platform over building tools for Platform as a Service (PaaS) (running software in the cloud). They are both racing to build new functionality, but it's hard to move from one vendor to another as there is no standardisation on the tools.

Everyday Boundary Risks

Although ecosystems are one very pernicious type of boundary in software development, it's worth pointing out that Boundary Risk occurs all the time. Let's look at some ways:

-

Configuration. When software has to be deployed onto a server, there has to be configuration (usually on the command line, or via configuration property files) in order to bridge the boundary between the environment it's running in and the software being run. Often this is setting up file locations, security keys and passwords, and telling it where to find other files and services.

-

Integration Testing. Building a unit test is easy. You are generally testing some code you have written, aided with a testing framework. Your code and the framework are both written in the same language, which means low Boundary Risk. But to integration test you need to step outside this boundary and so it becomes much harder. This is true whether you are integrating with other systems (providing or supplying them with data) or parts of your own system (say testing the client-side and server parts together).

-

User Interface Testing. The interface with the user is a complex, under-specified risky protocol. Although tools exist to automate UI testing (such as Selenium, these rarely satisfactorily mitigate this protocol risk: can you be sure that the screen hasn't got strange glitches, that the mouse moves correctly, that the proportions on the screen are correct on all browsers?

-

Jobs. When you pick a new technology to learn and add to your CV, it's worth keeping in mind how useful this will be to you in the future. It's career-limiting to be stuck in a dying ecosystem with the need to retrain.

-

Teams. if you're asked to build a new tool for an existing team, are you creating Boundary Risk by using tools that the team aren't familiar with?

-

Organisations. Getting teams or departments to work with each other often involves breaking down Boundary Risk. Often the departments use different tool-sets or processes, and have different goals making the translation harder.

Patterns In Boundary Risk

In Feature Risk, we saw that the features people need change over time. Let's get more specific about this:

- Human need is Fractal: this means that over time, software products have evolved to more closely map human needs. Software that would have delighted us ten years ago lacks the sophistication we expect today.

- Software and hardware are both improving with time: due to evolution and the ability to support greater and greater levels of complexity.

- Abstractions accrete too: as we saw in Process Risk, we encapsulate earlier abstractions in order to build later ones.

The only thing we can expect in the future is that the lifespan of any ecosystem will follow the arc shown in the above diagram, through creation, adoption, growth, use and finally either be abstracted over or abandoned.

Although our discipline is a young one, we should probably expect to see "Software Archaeology" in the same way as we see it for biological organisms. Already we can see the dead-ends in the software evolutionary tree: COBOL and BASIC languages, CASE systems. Languages like FORTH live on in PostScript, SQL is still embedded in everything

Let's move on now to the last Dependency Risk section, and look at Agency Risk.