Risk-First Analysis: An Example

The previous article, Fixing Scrum, examined Scrum's idea of "Sprints" and concluded:

-

The main purpose of a Sprint is to ensure there is a feedback loop. Every two weeks (or however long the Sprint is) we have a Sprint Review, and review the code that has been completed during the Sprint. In Risk-First parlance, we call this Meeting Reality. It is the process of testing your ideas against reality to make sure they stand up.

-

This Sprint Review is performed by the whole team. All the code must be completed by the end of the sprint in order that it can be reviewed. This introduces an artificial deadline to be met.

-

In order to meet this deadline (and because estimating is so hard) the Sprint must be planned carefully by the whole team, in a session of Planning Poker.

The diagram above shows this behaviour in the form of a Risk-First Diagram. Put briefly: risks (Schedule Risk, Feature Fit Risk) are addressed by actions such as "Development", "Review" or "Planning Poker".

If you're new to Risk-First then it's probably worth explaining at this point that one of the purposes of this project is to enumerate the different types of risk you could face running a software project. You can begin to learn about them all here. Suffice to say, we have icons to represent each of these kinds of risks, and the rest of this article will introduce some of them to you in passing.

On a Risk-First diagram, when you address a risk by taking an action, you draw a line through the risk.

Estimating Is A Poor Tool

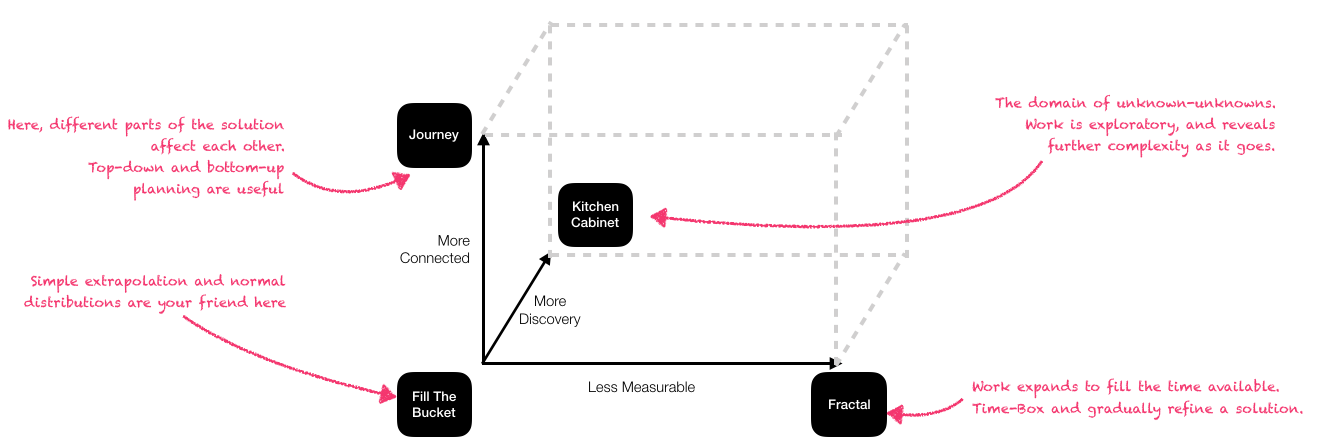

Seen like this, Planning Poker is a tool to avoid the Coordination Risk problem of everyone needing to complete their work for the end of the Sprint. But estimating is really hard: In this track so far we've looked at three different ways in which software estimation deviates from the straightforward extrapolation (a.k.a, Fill-The-Bucket) we learnt about in maths classes at school:

- Kitchen Cabinet: In this domain, there is hidden work. We don't know how much there might be. If we can break down tasks into smaller units, then by the law of averages and the central limit theorem, we can apply some statistics to figure out when we might finish.

- Journeys: In this domain, work is heterogeneous and interconnected. Different parts depend on each other, and a failure in one part might mean going right back to square one. The way to estimate in this domain is to know the landscape and to build in buffers.

- Fractals: In this domain, Parkinson's Law is king. There is always more work to be done. The best thing we can do is try and apply ourselves to the highest value work at any given point, and frequently refer back to reality to find out if we're building the right thing.

As a result, Sprints can often get derailed by poor estimating.

Scrum: The "cure" of estimating is worse than the "disease" of wasting stake-holder time.

Unintended Consequences

As shown in the above diagram, the emphasis on estimating as a way to plan sprints means that our measure of success is at the mercy of our ability to estimate. Trust in a team can be eroded not by their failure to "do engineering" but their failure to meet self-imposed deadlines. As a result, we end up with some unintended consequences, as shown in the table below.

| Planning Poker Focuses us on.... | At the expense of... |

|---|---|

| What can we commit to in a two-week window | Where we should be headed in the long-term. |

| Narrow goals, such as what we estimated could be done in a given time | The wider goals of the product or project in general |

| Ability to estimate | Concerns aside from estimation (such as, are we making the software too complex, too hard to understand, to difficult to change). |

Fixing It

How can we convert a planning session away from being estimate-focused and back to delivering us useful insights about what we are building? We want a tool that promotes the following:

- Consideration for what is going on longer-term in the project.

- Consideration of risks besides how long something takes. Sure, that's important, because it affects value, but it's not the only thing to worry about.

- Deciding what is important above what can fit into a sprint.

- Making Bets: what actions give the biggest Payoff for the smallest Stake?

A Scenario

I'm going to suggest a different approach to planning, which allows you to focus both on short-term goals and long term ones at the same time.

I'll walk through what this looks like by example to show how it works and then we can see if it addresses some of the issues with Scrum planning we've looked at.

In the diagram above, there are four tasks pulled off the backlog for consideration. (Obviously, we're keeping this simple - you might be looking at plenty more than this in a big team). We've got four simple ones for our product here:

- Fix a rendering bug that showed up when doing a demo a week or so back.

- Building a search function into the product, something the users have been asking for for a while.

- Refactoring the subscription system, after some stats revealed that a lot of users don't make it all the way through the process of upgrading from the free tier to the premium tier.

- Fix the Continuous Integration Pipeline: developers are complaining that the state of the build isn't being reported correctly, and some tests are failing randomly.

As it stands, it is impossible to say what we should be tackling next. In order to get to that, we have to answer three questions first. Let's look at those.

Question 1: What Do We Lose?

On a Risk-First diagram, tasks - or actions as we call them - are shown in "sign-post" style boxes, as shown above.

By fixing the rendering bug, we are trying to deal the problem that the software demos badly and the resulting risk that the potential customers don't trust the quality of our product. Risk-First diagrams show chronology from left-to-right. That is, on the left of the action is the world as it is now, whereas on the right is the world as it will be after taking some action. To show that our action will eliminate some existing risk, we can strike it out by drawing a line through it.

So, this diagram encapsulates the reason why we might fix the rendering bug: it's about addressing potential Reputational Risk in our product.

Question 2: What Do We Gain?

Let's move on to task 2, the Search Function, as shown in the above diagram.

As with the Rendering Bug, above, we lose something: Feature Fit Risk, which is the risk (to us) that the features our product is supplying don't meet the client's (or the market's) requirements. Writing code is all about identifying and removing Feature Fit Risk, and building products that fit the needs of their users.

So as in the Rendering Bug example, we can show Feature Fit Risk being eliminated by showing it on the left with a strike-out line. However, it's been established during analysis that the way to implement this feature is to introduce ElasticSearch, a third-party piece of software. This in itself is an Attendant Risk of taking that action:

- Are we going to find that easy to deploy and maintain?

- What impact will this have on hosting charges?

- Will it return useful results, or require endless "tuning"?

- Will we be "tied in" to this dependency going forwards?

If an action leads to new risks, show them on the right side of the action.

So, on the right side of the action, we are showing the Attendant Risks we gain from taking the action.

Question 3: What Is The Expected Return?

If we know what we lose and what we gain from each action we take, then it's simple maths to work out what the best actions to take on a project are simply pick the ones with the greatest Expected Return (as shown in the above diagram).

Upside Risk

It's worth noting - not all risks are bad! Upside Risk captures this concept well. If I buy a lottery ticket, there's a big risk that I'll have wasted some money buying the ticket. But there's also the Upside Risk that I might win! Both upside and downside risks should be captured in your analysis of Payoff.

While some projects are expressed in terms of addressing risks (e.g. installing a security system, replacing the tyres on your car) a lot are expressed in terms of opportunities (e.g. create a new product market, win a competition). It's important to consider these longer-term objectives in the Payoff.

The diagram above lays these out: We'll work hard to improve the probability of Goals and Upside Risks occurring, whilst at the same time taking action to prevent Anti-Goals and Downside Risks.

(There's a gentle introduction to the idea of Anti-Goals here which might be worth the diversion).

"Refactoring Subscriptions"

Let's go on to the third action, Refactoring Subscriptions to see this in action.

In the above diagram, we are showing that by removing Communication Risk around our product, we are improving our chances of reaching the goal of 50K subscribers. That's a big assumption - it could well be that the users don't complete the upgrade for other reasons. Maybe they find out the price during the upgrade and are put off, or they are being forced onto the upgrade screen by some dark patterns, but actually have no intention of upgrading the product at all.

"Fix The CI Pipeline"

Let's look at the last example: the action to fix the Continuous Integration Pipeline. A lot of development teams might consider this a no-brainer: "How can we possibly do useful work with an unreliable process?" Equally, a lot of product owners might feel the opposite: "why is the Development Team spending time on making their own lives easier when we have a marketing event next week and there are incomplete features?"

The above diagram tries to show how this is: on the left side, we have the Coordination Risk experienced by the Development Team. (Note the use of round-cornered boxes to show who the risks apply to). On the right side, we have the Deadline Risk experienced by the Sales Team.

On the face of it, it's clear why the Sales Team might feel annoyed - there is a transfer of risk away from the Development Team to them. That's not fair! But the Development Team Lead might counter by saying: "Look, this issue is slowing down development, which might mean this startup runs out of funding before the product is ready for launch. Plus it's causing a loss of morale in our team and we're having trouble retaining good staff as it is".

The above diagram models that. Fixing the CI Pipeline is now implicated in reducing Agency Risk, Coordination Risk and Funding Risk for the whole business and therefore seems like it might have a better Expected Return.

Judgement

But is that a fair assessment? How would you determine Expected Return in this situation? It's clear that even though we might be able to describe the risks, it might not be all that easy to quantify them.

Luckily, we don't really have to. If I am trying to evaluate a single action on my own, all I really need to do is answer one question: do I lose more risk than I gain?

All I need to do is "weigh up" the change in risks as best as I can. A lot of the time, the Payoff will be obviously worth it, or obviously not.

Ensemble

So far, we've been looking at each task individually, working out which risks we're addressing, and which ones we're exposed to as a result. If you have plenty of spare talent and only a few tasks, then maybe that's enough and you can get to work on all the tasks that have a positive Payoff. But if you're constrained, then you should be hunting for the actions with the biggest Payoff and doing those first.

Things change too when you have a whole team engaged in the planning process. Although people will generally agree on what the risks are, they often will disagree on the Probability they will occur, or the impact if they do. In cases like these, you might want to allow each stakeholder to "vote up" the risks they consider significant, or vote up the actions they consider to have high Payoff.

Some Points To Note

Let's talk about in which ways this is better or worse than Planning Poker.

- We've made explicit the trade-offs for carrying out pieces of work. If building the right thing is the most important thing we can do, then making sure the whole team are on the same page with respect to what the pros or cons might be.

- This isn't user stories: we're not describing a piece of work and asking how long it'll take. We're very clearly figuring out what the advantages and disadvantages are to attempting something. This is fundamentally a different discussion to a Scrum planning session.

- Estimates are de-emphasised: We're not coming up with hard estimates, but we are considering risks to deadlines, to budgets, to funding. As shown in the diagram above, there are plenty of risks associated with tasks taking too long.

- We're not planning, so much as weighing risks: A lot of project plans fall to pieces because they insist on certain events occurring at certain times. By talking about risk, we're acknowledging what we don't know.

Some Objections

Hard Work?

At this point, you might be thinking "this is a lot of work compared to Planning Poker, where I just have to pull a number out of my a**e every few minutes, representing how hard something is to do". Well, yes. I'm not going to sugar-coat this: product planning is actually really hard.

What we've developed here is a way to visually represent the trade-offs in the decision making process, so that we can engage the whole team in discussing them and charting the right developmental course.

This is Just Design

The model we are describing here is just a graphic representation of a discussion. It doesn't represent some "ground truth" about what to develop next - it merely gets everyone onto the same page to discuss what happens next.

The Participation Problem

One argument made for the Scrum planning game is that it gives everyone on the development team a voice. For many, this might be the biggest contribution of Planning Poker and we definitely don't want to lose that.

We've not looked at how Risk-First Analysis can be gamified in the way that Planning Poker is - we'll get to that. But first, let's look in more detail at the Story Point idea and see if it can be improved.