The Purpose Of The Development Team

Let's jump straight in.

Case 1: Lean

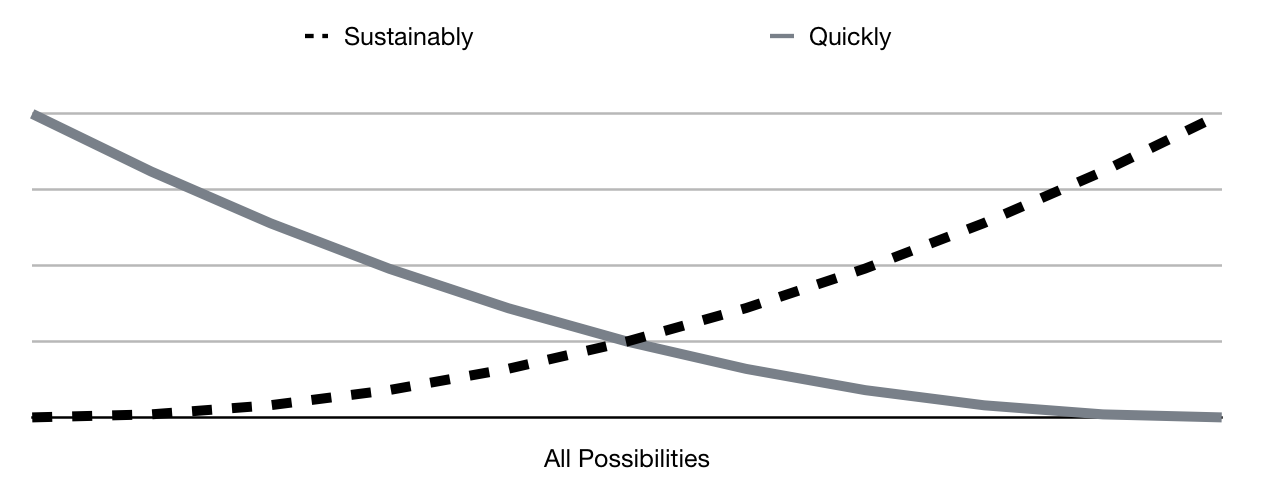

A manager I used to work with, Kevin, used to say that the Purpose of the Development Team was "Sustainably Deliver Value Quickly." Which apparently he got from a Lean handbook (maybe something like this one). It always seemed to me to be approximately right, except it bugged me. Eventually, I was able to put my finger on why:

- First, "sustainably" and "quickly" are somewhat at odds with each other. Cars aren’t optimised for both "energy efficiency" and "speed" and runners are either fast over short distances or long distances. My laptop makes trade-offs between battery life and weight: either extreme is bad, somewhere in the middle is useful. So "sustainably" and "quickly" implies that there is a balance to be achieved - what happens when you are forced to choose between the two? How do you choose?

- Second, my conception of value is that it is something you can make a sale on. Producing a product that customers value (at say £100-per-year) means that we can sell it for somewhere less than that (say £80-per-year). Therefore the development cost must come in at somewhere less than that (say £50-per-year) to allow the company to make a profit. But again, value didn't seem like the whole story either. Aren't there things to worry about besides value?

Case 2: Scrum

On a project not so long ago we chose to use Scrum, which advocates development being broken into "sprints" of maybe a few weeks long, commencing with planning and ending in a release. This worked out pretty well for a while, until one day there was a major outage in a critical piece of our infrastructure.

We could have washed our hands of it because there was a specific team for managing the infrastructure, but it seemed much more sensible that we abandon the sprint we were on and roll up our sleeves to help. After all, our product was dead-in-the-water without the infrastructure and this was impacting our users.

Had we stuck to Scrum religiously (following the rules, but not in an agile way), we might have waited until the end of the sprint and then considered whether to help the infrastructure team during the planning phase of the next sprint. But of course that would be a crazy interpretation of what it means to be agile.

Scrum's rule about working-to-a-sprint is well-meaning but not always applicable. How do we decide when to follow it and when not to?

Case 3: Technical Debt

Sometimes, I am faced with a conflict over whether to pay off technical debt or build new functionality. Sometimes the conflict will be with people in my team, or with stake-holders but sometimes it is an internal, personal conflict.

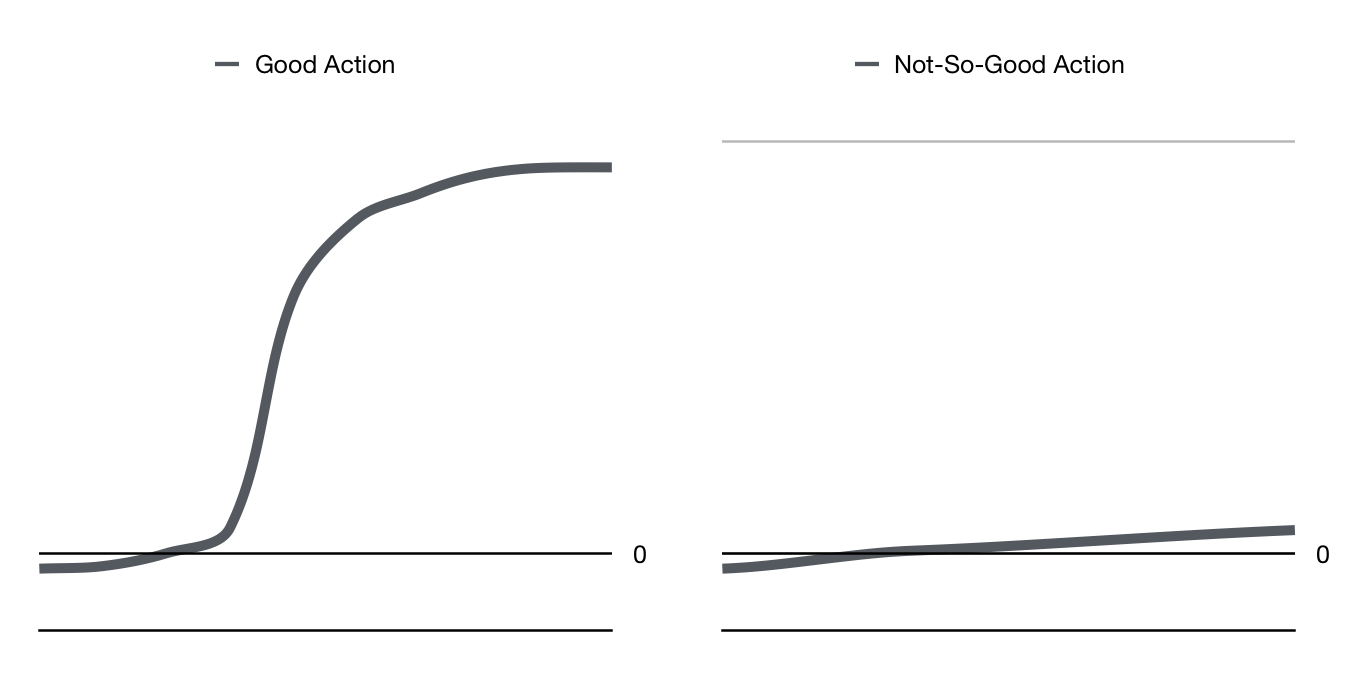

As the above diagram shows, paying off technical debt is sometimes the right thing to do when there is lots of unnecessary complexity in the code-base, but sometimes, it can be premature optimisation, and the shape of the software gets changed by new functionality so much that the work I put into clearing the technical debt is wasted.

What should I do?

Case 4: Agile Manifesto

The first statement of the Agile Manifesto is:

"Individuals and Interactions over Processes and Tools." - Agile Manifesto

What does this mean? I don't think it means "Individuals and Interactions are always more important than Processes and Tools” and it certainly doesn’t mean “throw away all your tools”. It is basically saying “previously, we’ve steered too much towards the right. We should steer a bit more towards the left”.

Is this helpful? Is such a relative statement telling us anything we previously didn't know? Usefully, perhaps, this describes a tautology that we may have been previously unaware of. I might have thought, "Individuals and Interactions? Processes and Tools? More of both, please!" But this statement is telling me that I can't have both, there is a trade-off, and I will have to choose.

But how do I choose?

A Virtue Between Two Vices

So, above I’ve given several cases of contradictory tensions within development. You can probably think of some more. In all of these, we are forced to use our common sense to try and steer a path between unreasonable extremes - a “virtue between the vices” as Aristotle termed it:

"In ancient Greek philosophy, especially that of Aristotle, the golden mean or golden middle way is the desirable middle between two extremes, one of excess and the other of deficiency." - Golden Mean, Wikipedia

But could there be a “general theory” somehow that avoids these contradictions? What would it look like? I am going to suggest one here:

"The purpose of the development team is to improve the balance of risk for achieving business goals as much as possible."

Now clearly, the troublesome clause in this statement is “balance of risk”. So, before we apply this to the cases above, let’s explain this concept in some detail by exploring three toy examples: the roulette table, buying stocks and cycling to work. Then we'll see how this impacts the work we do in software development more generally.

Example 1: The Roulette Table

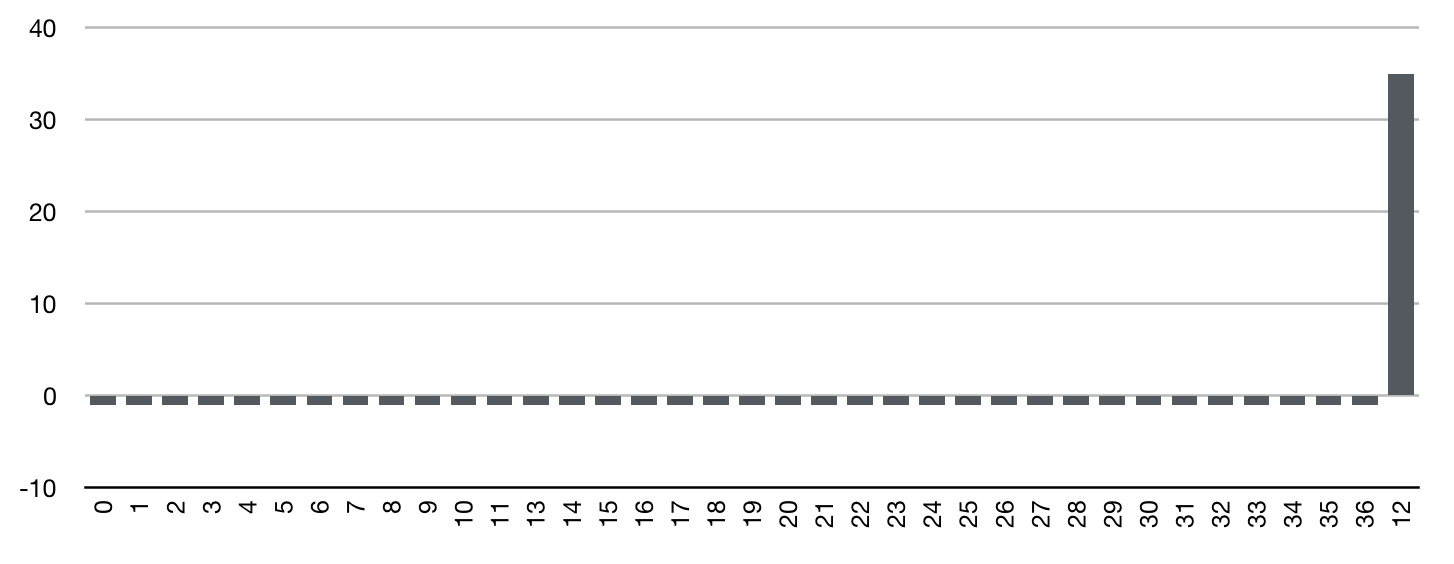

Let’s talk about “risk” for a bit. First, we’re going to consider the game “roulette”. If you bet a chip on a number (say, 12) in roulette and win, you win 35 chips (plus you get back your original chip). However, there are 37 places the ball can stop in roulette, and any of the other 36 will result in a complete loss.

The above chart shows the distribution of returns for this bet. Which hole the ball lands in (entirely randomly) is the independent variable on the x-axis. The return is on the y-axis. Most of the time, it’s a small loss, but there’s that one big win on the 12. (For clarity, in all the charts, I’ve arranged the x-axis in order of “worst outcome” to “best outcome”, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be arranged like this.)

In roulette, then, the balance of risk is against us: if we integrate to find the area under this chart, it comes to -1 chips. You could get lucky, but over time the house wins. It’s (fairly) transparent that this is the case when you enter the game, so people are clearly not playing roulette with the rational goal of maximising chips.

Example 2: Buying Stocks

In real-life, the distribution of returns differs in two key ways from roulette.

First, a roulette table presents us with a set of very discrete outcomes. Real life isn’t like that so much: there’s usually a sliding scale from “complete success” to “complete failure”, with a large middle-ground of so-so performance.

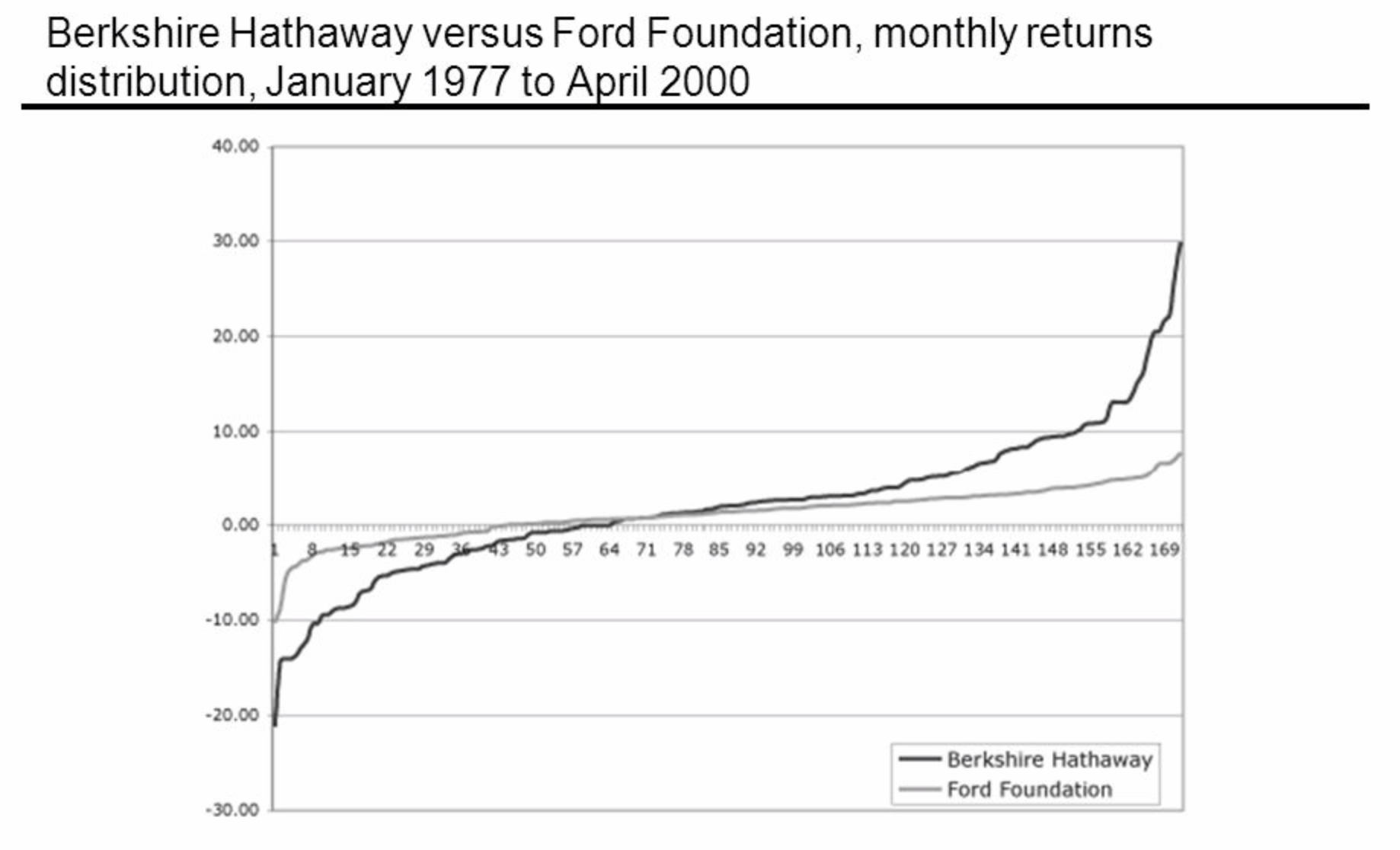

The chart above (from William T Ziemba) shows the returns-per-quarter of Ford and Berkshire Hathaway stocks over a number of years, with worst-performing quarters on the left and best-performing on the right.

Second, while you know ahead-of-time the chances of winning at roulette, you can only guess at the balance of risk for owning Berkshire Hathaway stock for the next quarter, even if you are armed with the above chart. Generally, owning shares has a net-positive balance of risk: on average you're more likely to make money than lose money, but it's not guaranteed - past performance is no indication of future performance.

Another question relating to this graph might be: which firm is generating the most value? Certainly, the area under the Berkshire Hathaway curve is larger but there is a bigger downside too. Is it possible that Berkshire Hathaway generates more value while taking on more risk?

When we consider buying a stock, we are going to build a model of the balance of risks (perhaps on a spreadsheet, or in our heads). This will be dependent on our own preferences and experience (our Internal Model if you will).

Example 3: Cycling To Work

Gambling is all about winning chips, and buying stock is all about winning money. Those are just ways of keeping score. But often, there is no exact score. Let's look at an example of that.

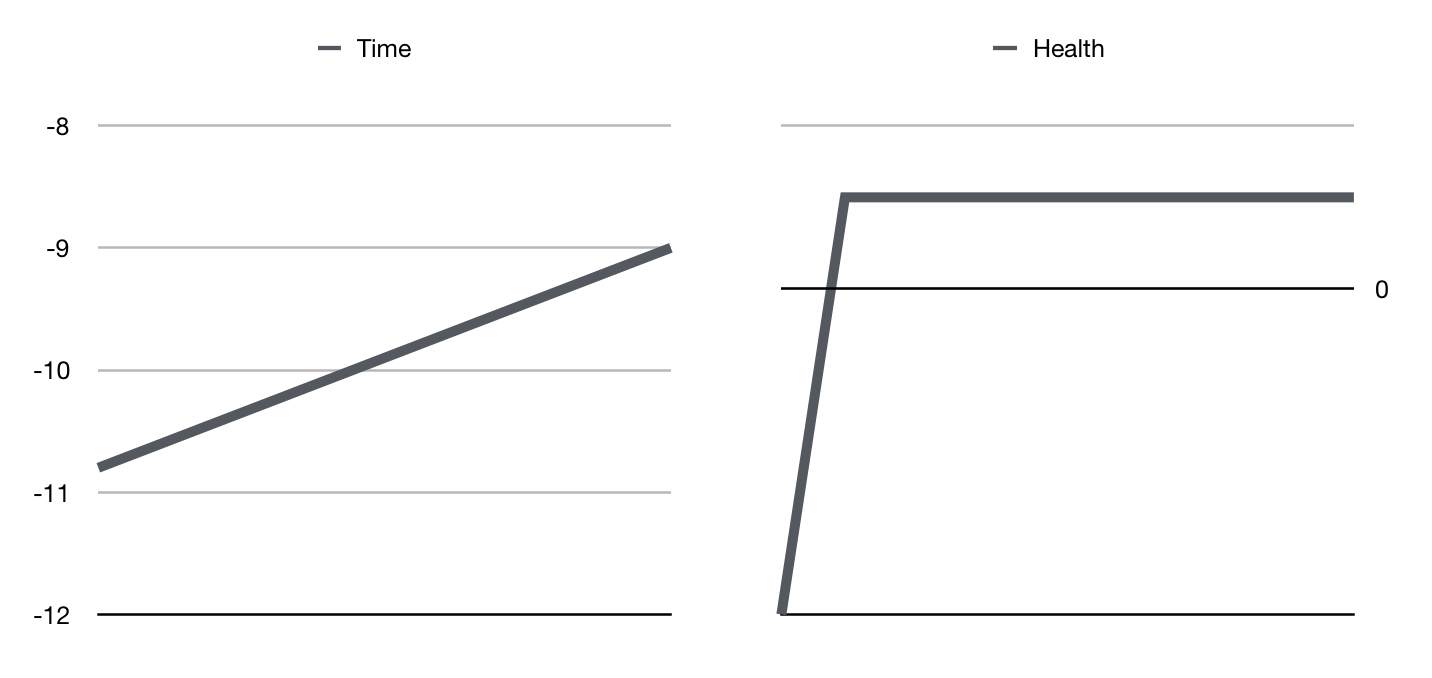

In the above chart, we have two risk profiles for cycling to work. On the left, we have the time taken. After a few week's cycling, we can probably start to build up a good Internal Model of what this distribution looks like.

On the right, we have health. There isn't a good objective measure for this. We might look at our weight, or resting heart-rate or something, or just generally have a good feeling that cycling is making us fitter. Also, there's probably a worry about having an accident built into this (the steep drop on the left), and again, there is no objective measure for judging how badly that might come off.

So we have three issues with health:

- It's hard to judge exactly how likely an accident is (the width of the bar) because they don't happen often, and

- it's hard to judge how costly it will be (the depth of the bar). Everyone judges this differently, and there's lots of evidence to suggest even the same person will judge this differently at different ages.

- It's hard to weigh it against time. If we want to reduce the time it takes to get to work, maybe by cycling faster, or going by a busier route, it's probably going to have a knock-on effect on the health risks. Whether this is worth it will depend on your appetite for health risks, against wanting to save time.

Back To Software

So, we've gone from the Roulette Table example where the whole risk profile is completely known in advance to the Cycling example, where the risk profile is hidden from us, and unknowable. Regardless, we will have our own Internal Model of the balance of risks which we use to make judgement calls.

Just as a decision over how fast to cycle to work changes the balance of risk, the actions and decisions we make in software development do too.

The difference is, while the cycling example was chosen to be quite finely balanced, in software development we should be looking for actions to take which improve the upside considerably more than they worsen the downside. That is, improving the balance of risk as much as possible.

This is shown in the above chart. Let's say you have two possible pieces of development, both with a similar downside (maybe they take a similar time to complete and this what is lost if it doesn't work out). However, the action on the left significantly improves the balance of risk for the project. Therefore, all else being equal, we should take that bet.

We don't want to just do work that merely shifts us from having one big risk to another, we want to do work that swaps out a large risk for maybe a couple of tiny ones.

Let's go back to our original cases:

- If I decide to suspend the current sprint to fix an outage, then that’s because I’ve decided that the risk of lost business, or the damage to reputation is much greater than the risk of customers walking because we didn’t complete the planned features.

- When the Agile Manifesto stresses Individuals and Interactions over Processes and Tools, it’s because it believes focusing on processes and tools leads to much greater risk. This is based on the experience that while focusing on individuals and interactions may appear to be a less efficient way to build software, following strict formal processes massively increases the much worse risk of building the wrong product.

- When we argue for fixing technical debt against shipping a new feature, what we are really doing is expressing differences in our models of the balance of risk from taking these actions. My boss and I might both be trying to minimise the risk of customers defecting to another product but he might believe this is best achieved by adding new features in the short term, whilst I might believe that clearing technical debt allows us to get features delivered faster in the long term.

- In the example of Sustainably vs Quickly, it's clear that what we should be doing is trying to avoid altering the balance of risks in a way that sacrifices too much Sustainability or Speed. To do this requires judgement in the form of an accurate Internal Model of the balance of risks.

Other Scenarios

In a way, this is not just about development teams. Any time a person is added to an organisation, the hope is that it will improve the balance of risk for that organisation. The development team are experts in improving the balance of technical risks but other teams have other specialities:

- The Finance team are there to avoid the risk of running out of money and ensuring that the bills get paid (avoiding Legal Risks).

- The Human Resources team are there to make sure staff are hired, managed and leave properly. Doing this avoids inefficiency, Reputation Damage, Morale Issues and Legal Risks.

- The best doctors have accurate Internal Models. They can best diagnose the illnesses and figure out treatments that improve the patient's balance of risk. Medical Students are all taught to 'first, do no harm':

"given an existing problem, it may be better not to do something, or even to do nothing, than to risk causing more harm than good." - Primum non nocere, Wikipedia.

As we saw above, Berkshire Hathaway is a riskier investment than Ford: the returns are likely to be higher, but so are the losses. Generally, by taking on risk, the more return (or value) you're likely to deliver, though the risk of going losing everything increases. This is why banks are required to hold capital against their risky investments: regulators want their contribution to the economic system to improve the balance of risks, not worsen it.

Impact

So how does this affect how we work in the development team? Clearly we're not merely delivering value. Value is a scalar (or single) quantity but we should be thinking about a vector (or a profile) of possible values.

If we were just delivering value, we might not:

- Build Unit Tests. After all, these add nothing directly to the customer experience.

- Keep Backups. Backups minimise the downside of storage failure.

- Add log statements. When things go wrong, these help you to work out why.

- Worry about ACID transactions. They slow things down, but they increase reliability.

- Work to minimise dependencies. Each dependency carries a risk that it might fail, causing problems in your software.

All of these actions are about insurance, which is about limiting downside-risk. None of them are of value per se to the client.

Bottom Line

If you are faced with a choice between extremes...

This is just a few simple examples and actually it goes much further than this. In Estimates I apply this idea to software estimating, and the next article, Coding Bets, I am going to show how knowledge of the balance of risk concept can inform the way we go about our day-to-day work as developers...