Fractals

Let's summarize what we've seen so far, and introduce a new way of estimating:

| Approach | Measurable Progress? | Homogeneous Work | Defined End-Point? |

|---|---|---|---|

| looks like: | "I know how far I have to go" | "Results equals effort" | "I know when I'm done" |

| Fill-The-Bucket | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kitchen Cabinets | No | Yes | Yes |

| Journey | Yes | No | Yes |

| Fractal-Shape | Yes | Yes | No |

So what is a fractal shape? Let's look at something called the Coastline Paradox:

"The coastline paradox is the counterintuitive observation that the coastline of a landmass does not have a well-defined length. This results from the fractal-like properties of coastlines, i.e., the fact that a coastline typically has a fractal dimension (which in fact makes the notion of length inapplicable)." - Coastline Paradox, Wikipedia

So, that means:

- The area of a landmass is a fixed amount, but

- the perimeter gets longer and longer, and more and more complex, the more accurately you measure it.

Let's look at a simple mathematical example of a shape like this, the Koch Snowflake.

As the animation shows, this shape is created by adding extra triangles to each side of the existing shape. As the number of steps increases, the area settles down to 8, whilst the total perimeter begins to increase more and more rapidly.

Relevance

The reason this is relevant to software (or hardware, for that matter) is that human value is very much like this. Consider the iPhone. The first version arrived in 2007, and looks much as it does today. The design began in 2005, and the designers knew they had a short period of time to bring this totally new idea to market, with the components they had available.

In successive years, new iPhones arrived, improving on the original. The screen improved, the networking improved, the software improved. The complexity of the iPhone and it's eco-system as a whole increased massively.

Just like the Koch Snowflake, above, the designers were creating an ever-more-complex perimeter of complexity around an area of consumer value. And, just like the Koch Snowflake, each new version increased the area of value.

Continuous Refinement

If your problem doesn't have an exact, defined end-goal, there is simply no way of estimating how long it will take to get there because you never will. And, if (like the Koch Snowflake), your solution will never be perfect, then the only approach is continuous refinement.

You might have some idea (selling hats for dogs?) of some interesting area of value on the Risk Landscape that you want to occupy, as shown in the above diagram.

Your best bet is to try and colonise the area of value as fast as possible by using as much readily available software as possible.

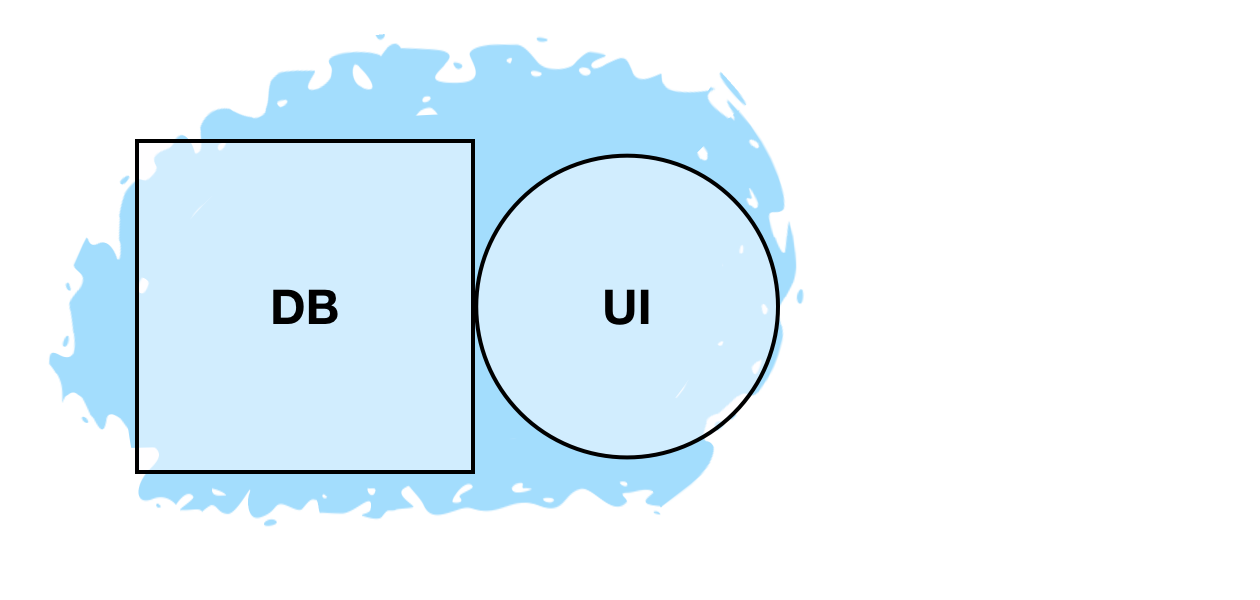

Maybe version one looks something like the diagram above: a few hastily-assembled components lashed together along with some rough-and-ready web pages. Hopefully, this kind of design will give you a better idea of what the right answer looks like.

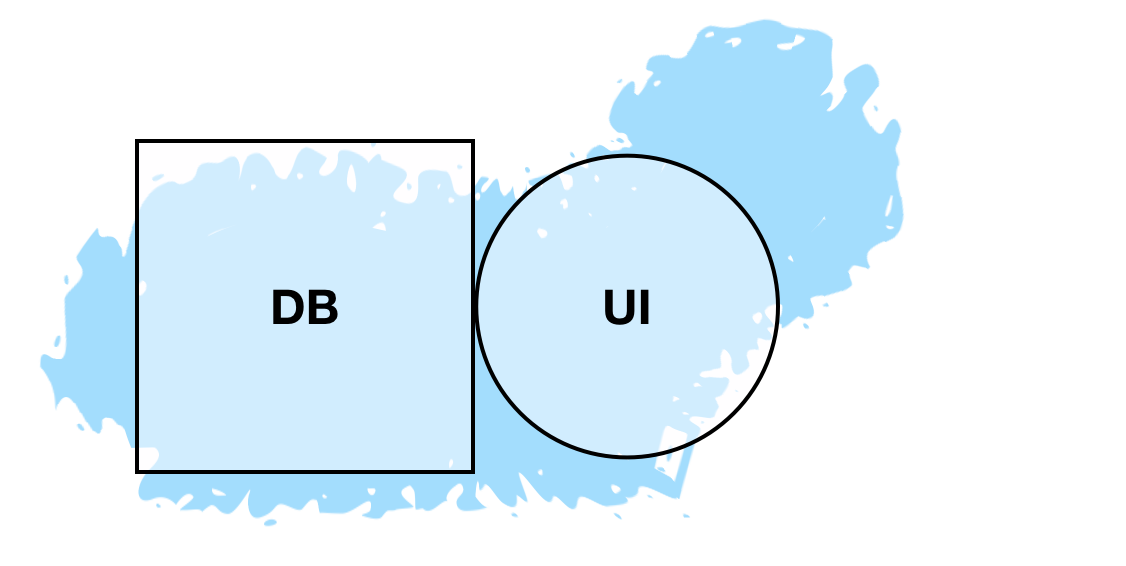

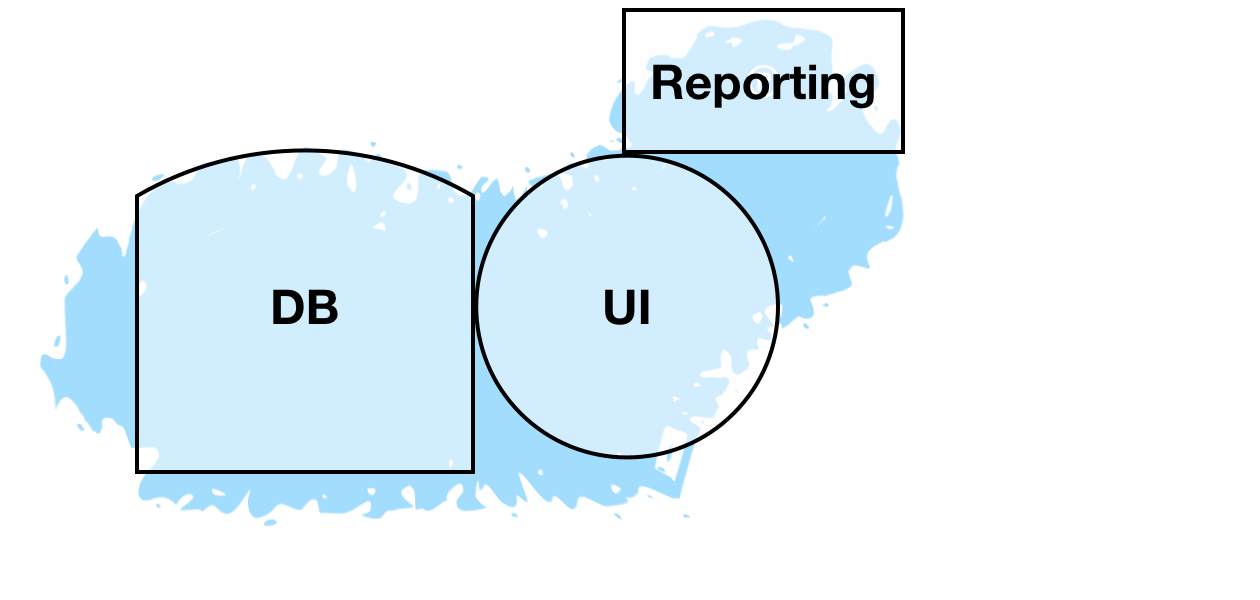

Releasing the first version might fill in some of the blanks, and show you more detail on the Risk Landscape. Effectively showing you a more detailed view of the coastline. Feedback from users will provide you with a better understanding of exactly what this fractal problem-space looks like.

As you go on Meeting Reality, the shape of the problem domain comes into focus, and you're able to refine your solution to match it more exactly.

Is it possible to estimate problems in the Fractal Shape domain? The best you might be able to do is to match two competing objectives:

- Building Product: By building functionality you head towards your Goal on the Risk Landscape. But how do you know this is the right goal?

- Meeting Reality: By putting your product "out there" you find your customers and your niche in the market, and you explore the Risk Landscape. But this takes time and effort away from building product.

With this in mind, you estimate a useful amount of time to go round this cycle, fixing the time but letting the deliverable vary.

Parsimonious Yachtsman

The fractal nature of many software development tasks is both a blessing and a curse. It's a blessing because it means that sometimes, software developers can achieve almost-miracles of creating huge chunks of value in no time at all. But that capability somehow ends up being an expectation. The startup idea of "throwing together an MVP (Minimum Viable Product)" is taken as gospel. Kyle Prifogle pushes against this when he writes:

"Lets explore this point more by means of an extended analogy. Suppose that you wanted to start a new business as a yachting captain... This is in many ways analogous to when a startup company decides that they want to serve the fortune 500, companies that have petabytes and beyond of data. However, you as a startup founder have to operate lean, and you are only willing to spend 10,000 dollars on a boat. If you were to walk up to the owner of the multi-million dollar yacht and say, I’ll give you $10,000 for that boat, you would be laughed off the dock. " - Kyle Prifogle, Dear Startup

Buying yachts is not in the Fractal problem space. It's much more Fill-The-Bucket: more money means more yacht. So, it's not a great analogy. But the point is that the expectation is for a value-miracle to occur, simply by adopting the practice of MVP or agile development.

Where To Find Fractal Spaces

Not all software development problems are squarely in the Fractal space, but those that are are generally tasks like building user interfaces, games, interactivity and usability. This is where the curse comes in: it's hard to know what to build and you are never done.

Although there are some high-profile wins with these types of problems, generally they are hard.

Applying Risk-First

Let's look at the conclusions we reached in Lock-In Risk:

- Human need is Fractal: this means that over time, software products have evolved to more closely map human needs. Software that would have delighted us ten years ago lacks the sophistication we expect today.

- Software and hardware are both improving with time: due to evolution and the ability to support greater and greater levels of complexity.

- Abstractions accrete too: as we saw in Process Risk, we encapsulate earlier abstractions in order to build later ones.

If we accept this problem of the fractal nature of human desire, then we have to contend with the fact that our software systems are always going to get continually more complex to serve it.

So that's four different styles of estimating. Let's try and put these together in Analogies