Journeys

A third way to conceive of software development is as a journey on the Risk Landscape. For example, in a startup we might start at a place where we have no product, no customers and some funding. We go on a journey of discovery and end up in a place where hopefully we have a product, customers and an income stream.

There are many ways we could do this journey, and many destinations. The idea of "pivoting" your startup idea feels very true to the Journey analogy, because that literally means changing direction. The place where we were headed sucked, lets go over here.

What does this journey look like in Risk-First terms?

As this diagram shows, at the start we have plenty of Feature Fit Risk: if we have no product, then it definitely doesn't fit our customer's needs! Also we have some amount of Funding Risk, as at some point the money will run out.

After that, we use every trick in the book called "product development" to get to a new place on the Risk Landscape. This place (hopefully) will have a better risk profile than the one we came from.

If we're successful then yes, we'll have the Operational Risk of running a business, but hopefully we'll be in a better position than we started.

A London Example

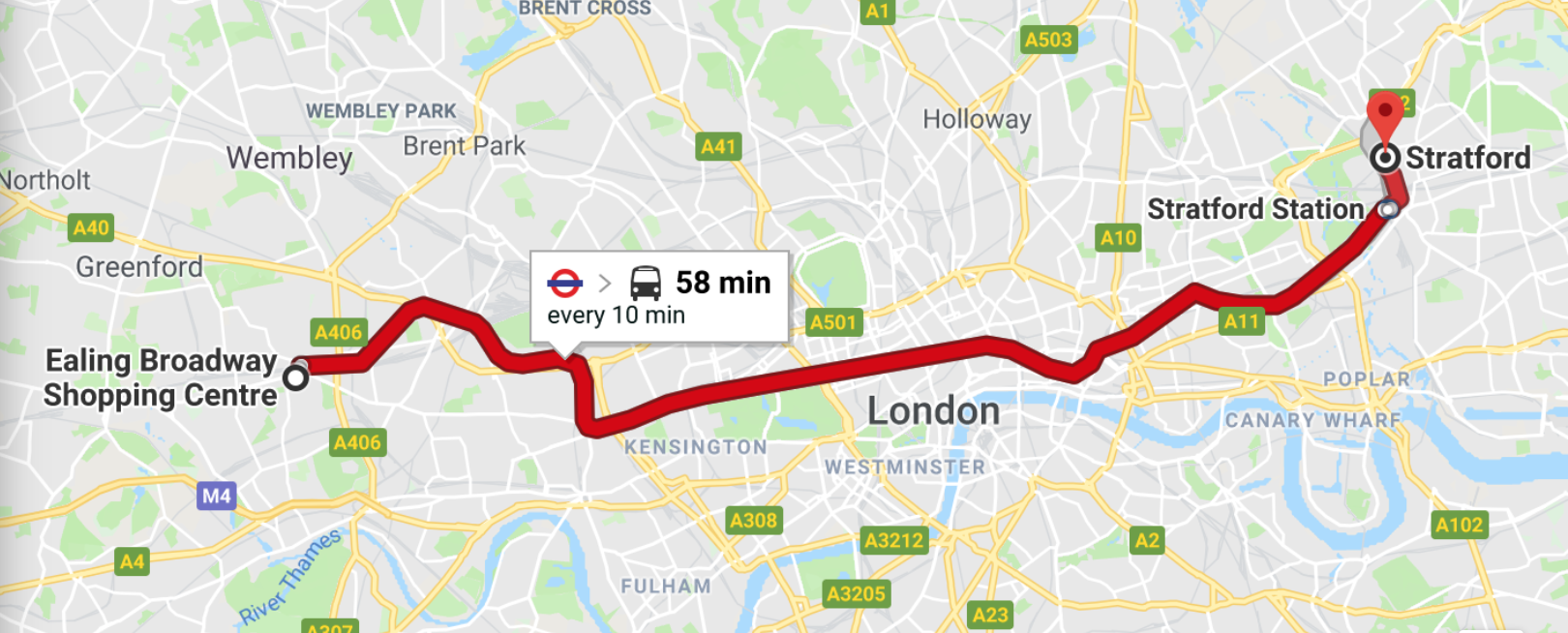

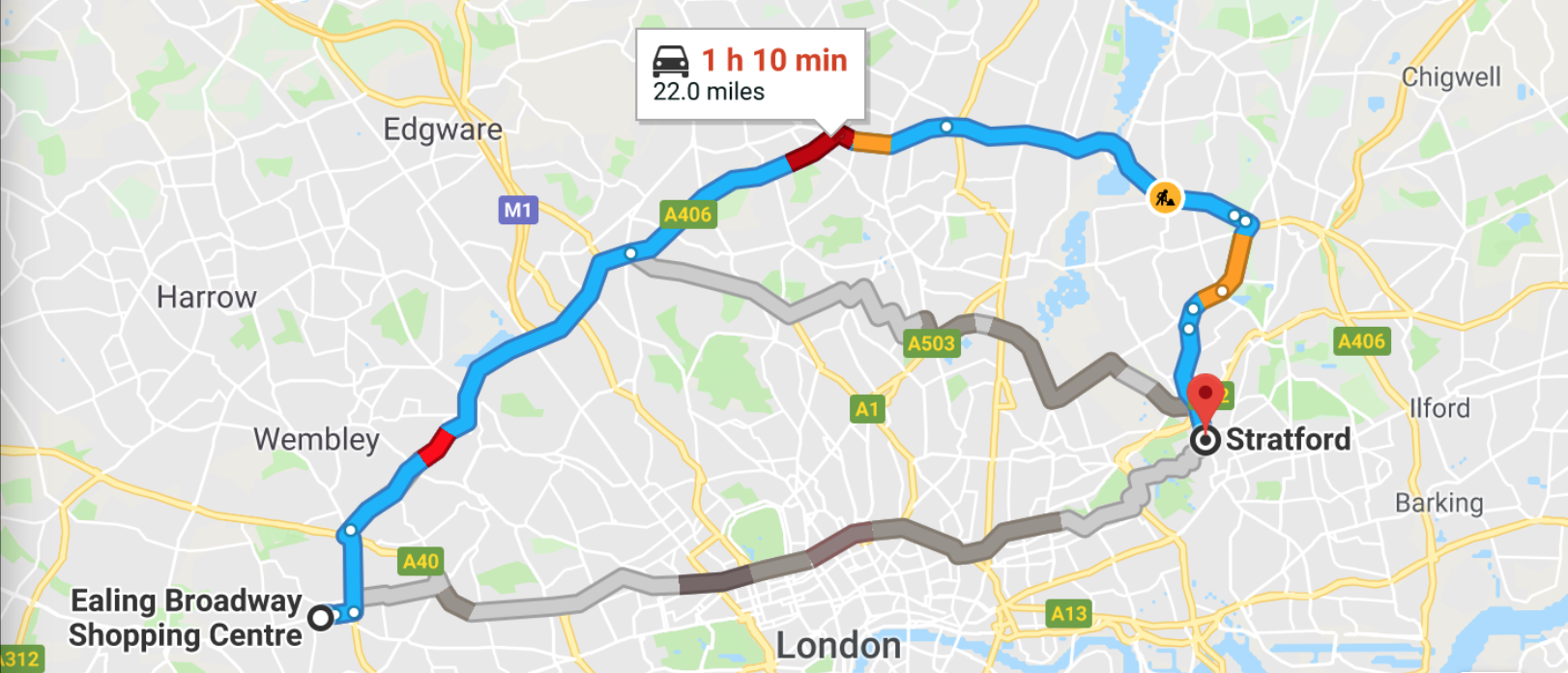

If you were travelling across London from Ealing (in the West) to Stratford (in the East) the fastest route might be to take the Central Line. You could do it via the A406 road, which would take a bit longer. It would feel like you're mainly going in completely the wrong direction doing that, but it's much faster than cutting straight through London and you don't pay the congestion charge.

In terms of risk, they all have different profiles. You're often delayed in the car, by some amount. The tube is generally reliable, but when it breaks down or is being repaired it might end up quicker to walk.

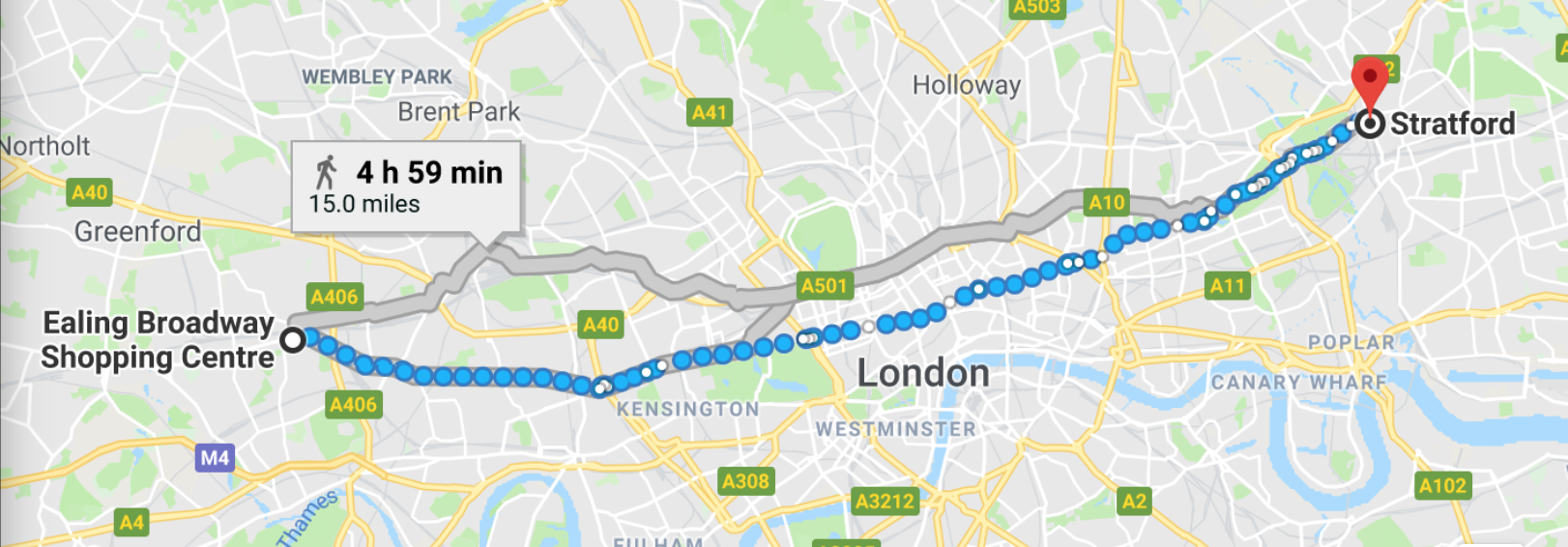

If you were doing this same journey on foot, it's a very direct route, but would take five times longer. However, if you were making this journey a hundred years ago that might be the only choice (horseback might be a bit faster).

Journey Risks

In the software development past, building it yourself was the only way to get anything done. It was like London before road and rail. Nowadays, you are bombarded with choices. It's actually worse than London because it's not even a two-dimensional geographic space and there are multitudes of different routes and acceptable destinations. Journey planning on the software Risk Landscape is an optimisation problem par excellence.

How can we think about estimating in such a domain? There are clearly a number of factors to come into play:

- For individual parts of the journey, we could use a Fill-The-Bucket approach, and look at things like expected travel time, mean travel time or reliability.

- Chances are, we're going to need to join up several different pieces of transport: maybe some on-foot, some by road, some by rail.

- It's a really good idea to build in buffers if you're relying on services that are infrequent (like flights or trains).

- Cost is a factor.

- You can easily go the wrong way, or end up in a dead end. That's going to seriously impact your schedule.

- You might not be working with complete, up-to-date maps and timetables, but a general idea for the territory.

Estimating Journeys

To estimate how long a journey will take really means to plan it, at some level. As we saw above, the unplanned journey (walk in the direction of your destination) can take five times as long as the planned version.

For this reason, planning is really important. Generally, what planning means is that we do some kind of hierarchical decomposition of the problem, breaking it down into smaller and smaller components until we're happy with both the overall structure and the individual leaf-elements.

And this approach is the same as the one we would use when creating a task breakdown of a project plan, or trying to come up with an estimate for a story in a development project.

1. Break Down The Journey Hierarchically

If I am travelling from my house in the UK to my brother's house in France, then hierarchically, the problem might look like:

- The problem of getting from England to France a. The problem of travelling from my house in England. b. The problem of travelling to my brother's house in France.

The problem has been decomposed hierarchically, based on my understanding of geography.

2. Evaluate the Alternatives

Having broken down the problem, I can start at the top of the hierarchy and try and find the least risky option at that time, considering the various factors we identified above.

There are alternatives - I might fly or I might take a ferry, or I might decide to go on the train. All of which have their pros and cons.

3. Move Down the Hierarchy

Having figured out a plan for the top level (say, flying), I can then concentrate on the next level, getting from my house to the airport. For this I might consider the train, but then I am left with the further problems:

- Getting from my house to the station

- Getting from the station to the airport.

... and so on. There is always the possibility that some lower-level travel-problem is unsolveable, and then I have to back-track up to a higher level and solve in a different way. No trains on a Sunday? Ok, maybe I should drive instead...

4. Stop

Eventually, I decide I've done enough planning. How? I stop at the point where I'm happy with the risks I'm taking, or unable to mitigate them further. Perhaps I've added enough buffer-time into my plan to cater for delays on the train, and I have taxis booked, or maybe I value my time now more highly and I'm optimistic about figuring it all out on the day.

Back To Software

This should look a fair bit like software architecture: often, we sketch out the big parts of the system - the programming language, the database, the main use-cases - and figure out how these fit together. Then, we leave the details to chance.

At the other extreme, if we're estimating a single story, we can break down work like this. For development tasks which look like a journey, this is what I'm doing. "If I build the Foo component using Spring and the Bar component in HTML, I can join them together with some Java code..."

Further, as we solve problems in our code-base, we break them down into smaller and smaller parts.

So Journey Estimating is three things all at once:

- It's design, because I've broken down the work into lower-level components, evaluating the risk as I go.

- It's a plan of how to get from A to B, which might well turn out to be wrong, when we get stuck into the details.

- It's a schedule, because I'll have an idea of how long each piece might take to do.

Meta Analysis

So, we now have a third type of estimating. Again, very different from the first two. But again, there are obvious similarities with what we do in the world of software, because it's so easy to go the wrong way or overlook a short-cut.

I've been on projects where a team has toiled long-and-hard to get a database working, only to find out that there was a better, different one available that would do the job for them with way less effort. I've watched people struggle to build their own languages and compilers, only to realise later that actually all they needed was to use the ones that were there already.

In software, it's easy to head off on-foot by accident, overlooking the fact that someone has built the motorway.

In fact, my argument is that, in a world of millions of open-source projects, the art of software development is to a large extent to be able to stitch together a selection of pre-written components in much the same way as I might stitch a journey plan together from a series of pre-existing travel options.

Applying Risk

Estimating then becomes the art of:

- Breaking down the functionality required into separate parts

- Assigning the responsibility of each part to a particular pre-existing component

- Working out how long it'll take to glue them all together

- Not being wrong about the feasibility of the plan in the first place.

To achieve point (4), once an estimate is in place, the Risk-First way to proceed would then be to tackle each part in order, from the riskiest and most-likely-to-fail, to the most reliable. This approach front-loads finding out if the plan is suspect.

But, there is yet another way of looking at what's needed to estimate: Fractals.