Analogies

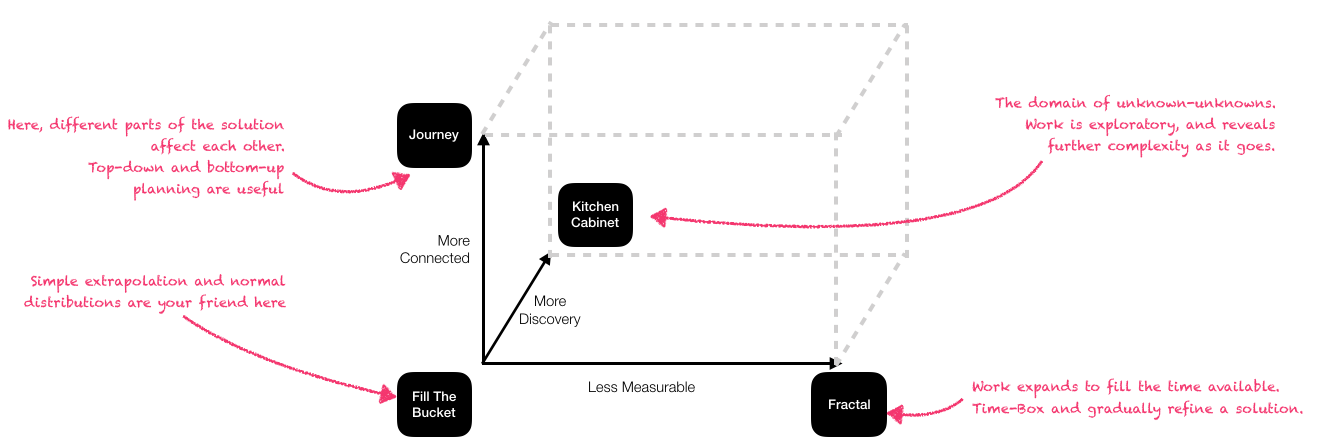

So far, this track of articles has tried to bring the problems of estimating software projects into focus by identifying different estimation domains and analogies for each domain. Let's recap:

- Fill-The-Bucket: This is the easiest domain to work in. All tasks are similar and uncorrelated. We can extrapolate to figure out how much time the next n units will take to do.

- Kitchen Cabinet: In this domain, there is hidden work. We don't know how much there might be. If we can break down tasks into smaller units, then by the law of averages and the central limit theorem, we can apply some statistics to figure out when we might finish.

- Journeys: In this domain, work is heterogeneous and interconnected. Different parts depend on each other, and a failure in one part might mean going back to the drawing board entirely. The way to estimate in this domain is to know the landscape and to build in buffers.

- Fractals: In this domain, Parkinson's Law is king. There is always more work to be done. The best thing we can do is try and apply ourselves to the highest value work at any given point, and frequently refer back to reality to find out if we're building the right thing.

In Risk-First, one of the main messages has been that it's all about your Internal Model. If you have a good model of the world, then you're likely to be able to Take Actions in the world that lead you to positions of lower risk.

So the main reason for identifying all these different problem domains for estimation has been to improve that internal model.

Connecting The Dots

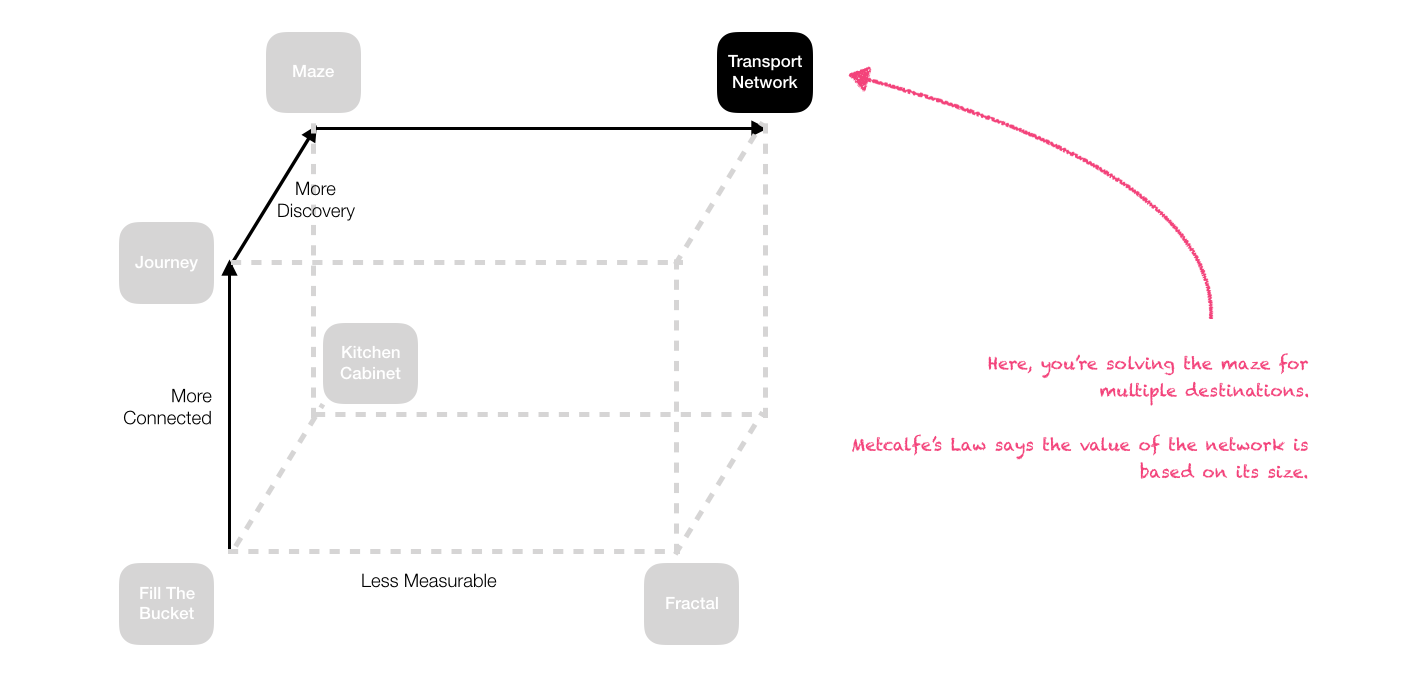

Hopefully, you should be able to draw a line through each of these domains and see that there are examples from the world of software development that fit in there. Rather than understanding estimating as a thing which goes wrong frequently, and throw it out as a tool, you might be able to place your problem in this space, and decide which of these axes caused you the issue.

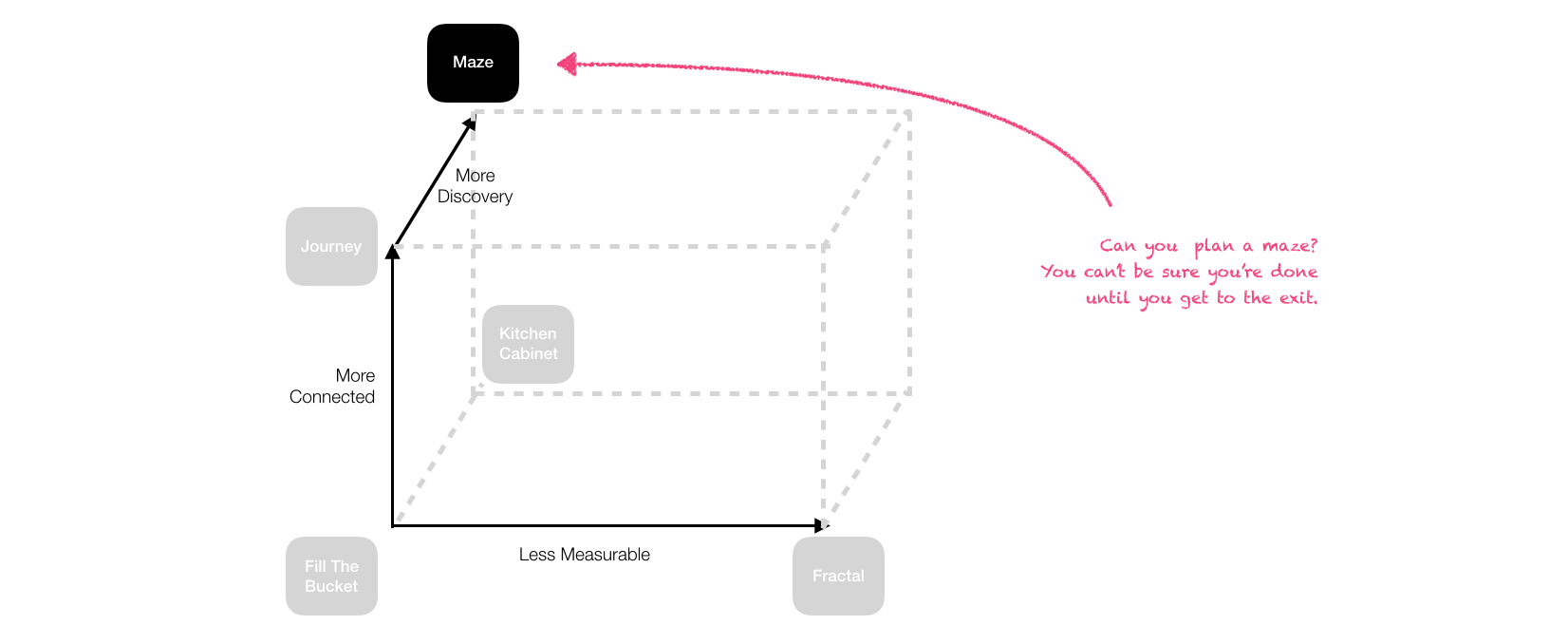

For the rest of this article, I'm going to go out on a limb, and describe, through increasingly preposterous analogies, how we can arrive at an analogy for the top-right of the above diagram. Now, arguably - that's going to be completely pointless: we have enough analogies already since we've described each dimension! However, unlike the other chapters this is going to be a fairly easy ride so just go with it.

Journeys + Cabinets = Mazes?

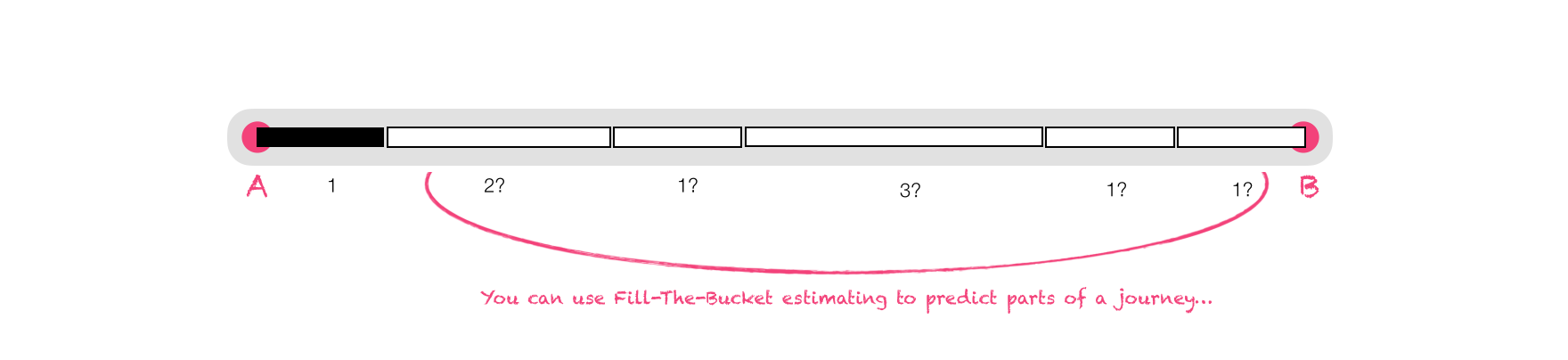

As we discussed in Journeys, there are plenty of problems in getting from A to B. But to help you we have:

- Maps: so we can plan our routes via those which already exist, and

- Closeness: the closer you are to your destination, the nearer you are to done (which is great for walking and driving, but tends to fall down somewhat when we have to wait for buses or make a detour to the airport).

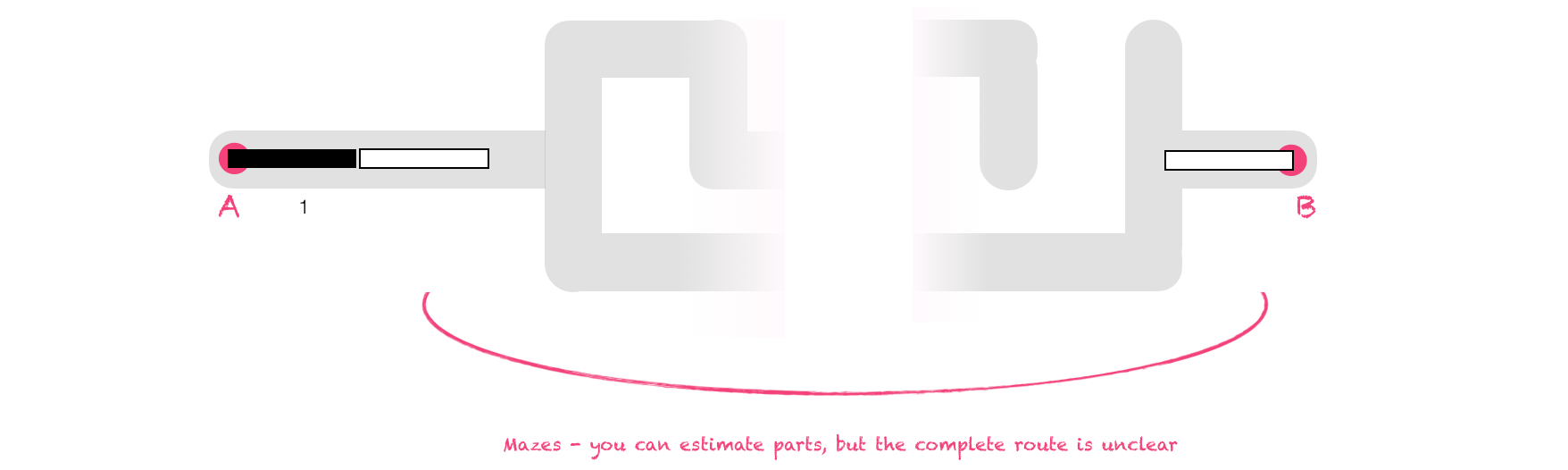

What happens when you relax those constraints? If there is no map and the closeness heuristic isn't available, you're in a maze. You can't tell how "done" you are in a maze by judging your distance to the exit point - you may be heading to a Dead End anyway!

Software development is littered with dead ends:

- The database you thought would be a good fit, but didn't work.

- The library you thought would solve your networking problems, but turned out to be unable to work through the firewall.

- The algorithm that promised to recognise faces in images only works three times out of four.

A very famous example of this might be the "Summer Intern Computer Vision" project, outlined by Seymour Papert in 1966:

"The summer vision project is an attempt to use our summer workers effectively in the construction of a significant part of the human visual system" - The Summer Vision Project, Seymour Papert

Maybe this is an unfair (and perhaps apocryphal) example but we've been stuck in the "Computer Vision" maze ever since.

Mazes + Fractals = Transport Networks?

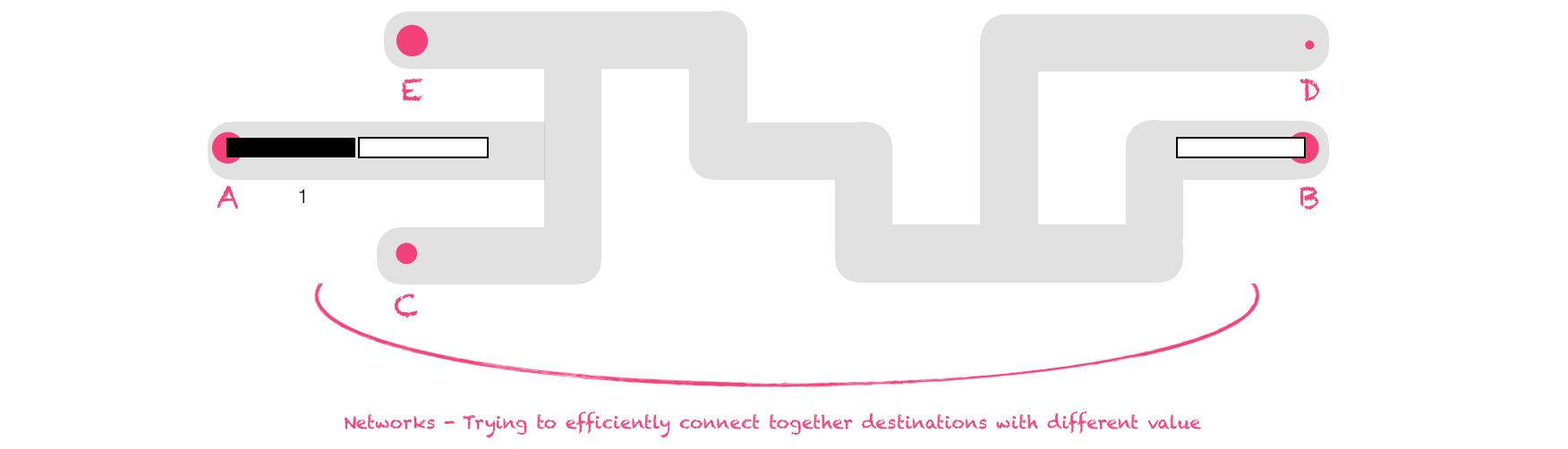

In a maze, you're trying to get from point A to point B. However, when we throw fractals back into the mix, we're wanting to get to a whole lot of different places, and there is different value in different places.

This is a lot like a country-wide transport network:

- Large cities are connected together with efficient transport options because people are going to make that journey a lot. Therefore, these are high value routes.

- Small, far-away outposts are poorly connected to the rest of the network - maybe by dirt roads or precarious mountain passes.

Metcalfe's Law

The total value of a network is based on the number of people (towns / machines / whatever) it connects. This means that while connecting small out-of-the-way places might apparently not make sense from a marginal-cost perspective, it may make sense from the perspective of the total value of the network.

This is encapsulated in Metcalfe's Law, which says the value of a network is based on the square of it's size:

"The law has often been illustrated using the example of fax machines: a single fax machine is useless, but the value of every fax machine increases with the total number of fax machines in the network, because the total number of people with whom each user may send and receive documents increases. Likewise, in social networks, the greater number of users with the service, the more valuable the service becomes to the community. " - Metcalfe's Law, Wikipedia

Exploring vs. Road-Laying

Building a transport network starts with exploring. Once a connection is established, then capacity can be addressed with engineering.

It's easy to get these two confused in software and worry up-front about capacity and design decisions, while in reality you're supposed to be exploring the space of the possible. In essence, this is what Donald Knuth is saying with his famous quote:

"We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. " -Donald Knuth, Wikipedia

So it feels to me that the transport network analogy for software development is a good one. Are you exploring, or are you engineering? This is a critical distinction for deciding how to work on a project.

Personally, when in the exploring mode, I will focus on proving ideas, lashing classes together. I know that I'm very likely to delete them, or tear them to pieces at the next revelation. For this kind of work, I am unlikely to write unit tests - they'll just slow me down. My code will be full of bugs and technical debt but it doesn't matter if I reach the enlightenment at the end of the maze.

Conversely, when in the engineering mode, I am trying to create software that will survive the rigours of use. The ideas will have been tested, it's just a case of making the implementation good enough. Here, I will be building tests, considering Single-Points-Of-Failure and assessing bottlenecks.

Turns out, I am not the only person to draw this analogy:

"Software projects exist on a continuum between the Lewis and Clark expedition, and laying down freeway. Knowing what kind of project you’re on can be the difference between success and failure." - Coding styles: Are you Lewis and Clark or building an interstate?, Stan James

Moving On

So I find the transport network analogy to be a useful one. But actually it ties in nicely with where this track goes next.

Maintaining a transport network is a balancing act. In an ideal world, every destination would be connected with every other. In reality, we adopt hub-and-spoke architectures to minimise the cost of maintaining all the connections. In essence, turning our transport network into some kind of hierarchy.

It's time to look at Fixing Scrum.