The Evolution Of Open-Source

In the 00's the Internet disrupted the music industry entirely. People walked around with iPods full of songs that they had downloaded using Napster or Limewire and the era of the physical-medium began to end, taking with it the cozy business models of the record companies.

Eventually, music makers figured out that streaming with subscription fees was the right model to get people to pay for songs. (Spotify being the main one). The advantage of streaming was that it was even easier to use than pirating the music, and had none of the guilt attached.

Television and film are following the same way, as is commercial software, as evidenced by Adobe Creative Cloud, Microsoft 365, and a million other SaaS providers.

Rug Pull

But customers of commercial software have become wise to the proprietary equivalent of the rug-pull, or "doing an Oracle": woo the customer, make them depend on you, then milk the relationship for all it's worth.

Increasingly, the world is turning to open-source software. As the picture at the top shows, with the right licensing, open-source is composable. The software systems of the future (proprietary or otherwise) are built using the Lego bricks of open-source.

Why is this? Straight open-source is thankfully immune to the rug-pull manipulation: you know you'll at least have access to the source code. But, is that better?

The Basic Dilemma

Software is to some extent a living thing.

Software cannot stay useful without effort: it has to change and adapt to the world around it. This is a type of evolution, where the agent of evolution is developer time and skill. The most successful software is able to attract large numbers of developers and evolve faster. Worse software eventually becomes abandoned and dies.

There are two main reasons developers will improve some software - we'll call these "Feedback Loop A" and "Feedback Loop B".

Feedback Loop A: Capitalism

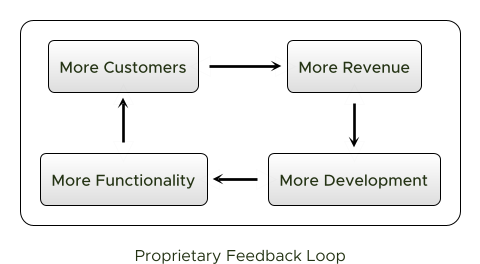

In Feedback Loop A, developers are paid to improve software, and money is used as the signalling system to get them to do this. Proprietary software tends to fall into the first category (the money has to come from somewhere).

This is shown in the above diagram. When you're building proprietary software, you want to create a feedback loop wherein the software grows and evolves. More customers, more functionality, more developers, more money. Or, if not that - at least something self sustaining.

Feedback Loop B: Shared Value

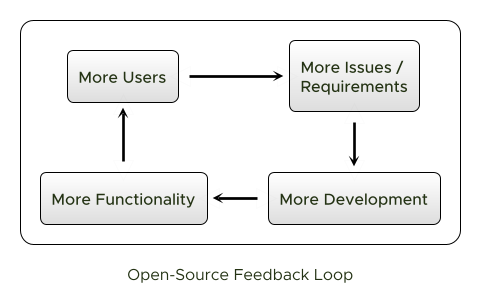

In Feedback Loop B, developers improve the software because they benefit from the improvements themselves... and so does everyone else.

Open-source usually falls into the second category. This is shown in the above diagram: as a piece of Open-Source software becomes more popular, it generates more value, but also picks up more issues. Developers rally to fix those issues and the functionality increases. More functionality, more developers, more value.

But this is a dilemma because it seems you can't have it both ways: you have to pick one. If you want to sell your code (whether as a SaaS or with licenses) then it's dangerous to open-source it, since another company could come along and copy your business model.

A Synergy?

Issues like Log4Shell really underscore the importance of secure open-source software. Huge commercial organisations are being built on top of open-source now and it is in their interests to see that it is properly funded and maintained.

It is simply in no-ones' interests to let popular open-source libraries' feedback loops fall apart. Somehow, they need to be kept looping.

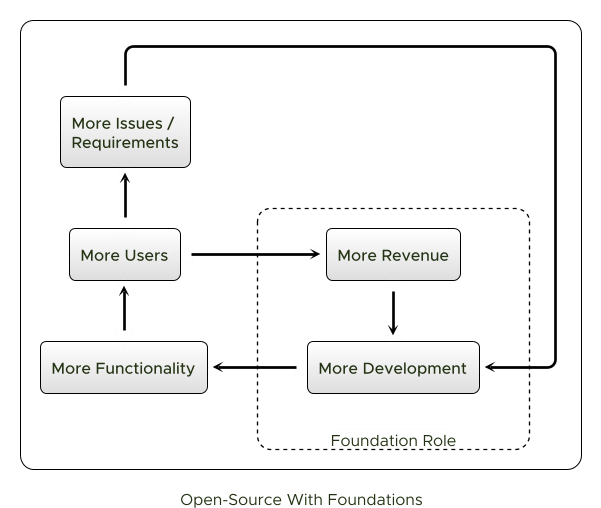

The solution to the above dilemma is to introduce the aggregator.

Just as aggregators like Spotify showed how to defeat the issue of music piracy and re-establish a feedback loop in the music industry, we need aggregators for open-source too. Software Foundations are well-placed to fill this role.

As shown in the above diagram, foundations need to step into this role and make sure they provide commercial funding and development to important open-source projects. Both feedback loops are at work here: developers can improve the open-source software via pull-requests just as before. But, there is also the feedback loop of financial backing to ensure software stays up-to-date.

Surely, this is the best of both worlds?