COVID, Agile, ChatOps

COVID, Agile, ChatOps

This is a presentation prepared for FINOS' Open Source Strategy Forum, 2020. It is quite a lot about chat-bots and the Symphony Java Toolkit, but there's some stuff on Agile and ChatOps that makes it relevant to readers of Risk-First.

Hi Thanks for joining my talk: Bots, ChatOps, COVID and The Symphony Java Toolkit.

I’m also going to talk about Hackathons, Work-flow, Agile, GitHub and Open-Source as we go. Hopefully, I’ll be able to tie all that together into some consistent whole, but we’ll see.

And, I know that might be a confusing bunch of disparate buzzwords, but over the next few minutes, I’ll unpack all those, and hopefully, you’ll see how they all fit together.

Let’s start with Symphony.

This is a screenshot from Symphony. It’s a chat platform. I’m imagining that lots of people here today are very familiar with chat platforms now, and use them in their day to day work.

This one is Slack. It’s pretty similar to Symphony. You’ve got your chats down the left-hand side there. Box at the bottom for entering text.

And this one is Teams, from Microsoft. Again, same kind of layout. I guess you could say that there’s a lot of “convergent evolution” going on here. All of these platforms share a lot of the same features, and we’ll talk about some of those features as we go.

You might have even seen in the press lately how the guys building Slack are trying to sue Microsoft over exactly that issue: not only is Teams similar to Slack, but they’re trying to push Teams out to everyone. They’re using their dominance of Office tools to try and muscle in on Slack’s territory.

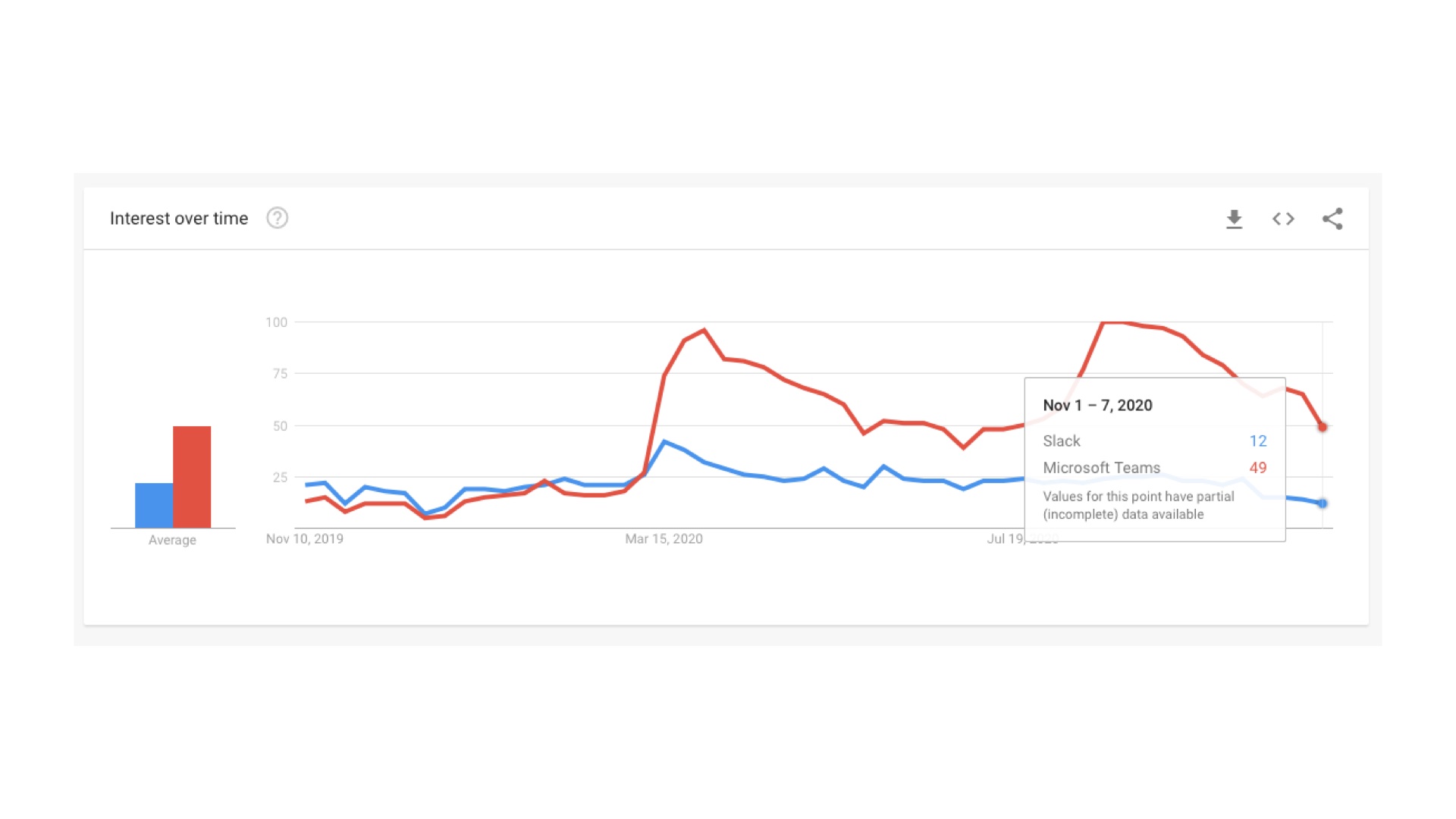

Here’s a Google trends chart of those two. You can see: Teams is now a lot more popular as a search term than Slack, which explains why Slack are getting mad.

Now, what’s really interesting, to me at least, is what happens in March. Suddenly, Teams gets this huge boost. Slack, a smaller one. Loads more people using it. I’m pretty convinced that this is COVID related. It ties into when we were all starting to work from home.

Somehow, Microsoft got a big COVID-related uptick here, which really helped their notoriety.

Now, Symphony isn’t on this graph. Symphony is kind of a small player compared to Slack and Teams. It’s super-specific to the finance industry, and has really good market share there. The reason being, it has a much better story with regards to compliance and security, which is something that banks and financial regulators are really keen on.

At Deutsche Bank, we saw the same thing as in this chart - the number of messages going over Symphony since about March, has doubled.

And, that makes sense. People can’t face-to-face chat so much anymore. Obviously, COVID has changed the way we all work. And, Teams, Slack, Symphony, they’re the kind of tools that we use to interact with each other now.

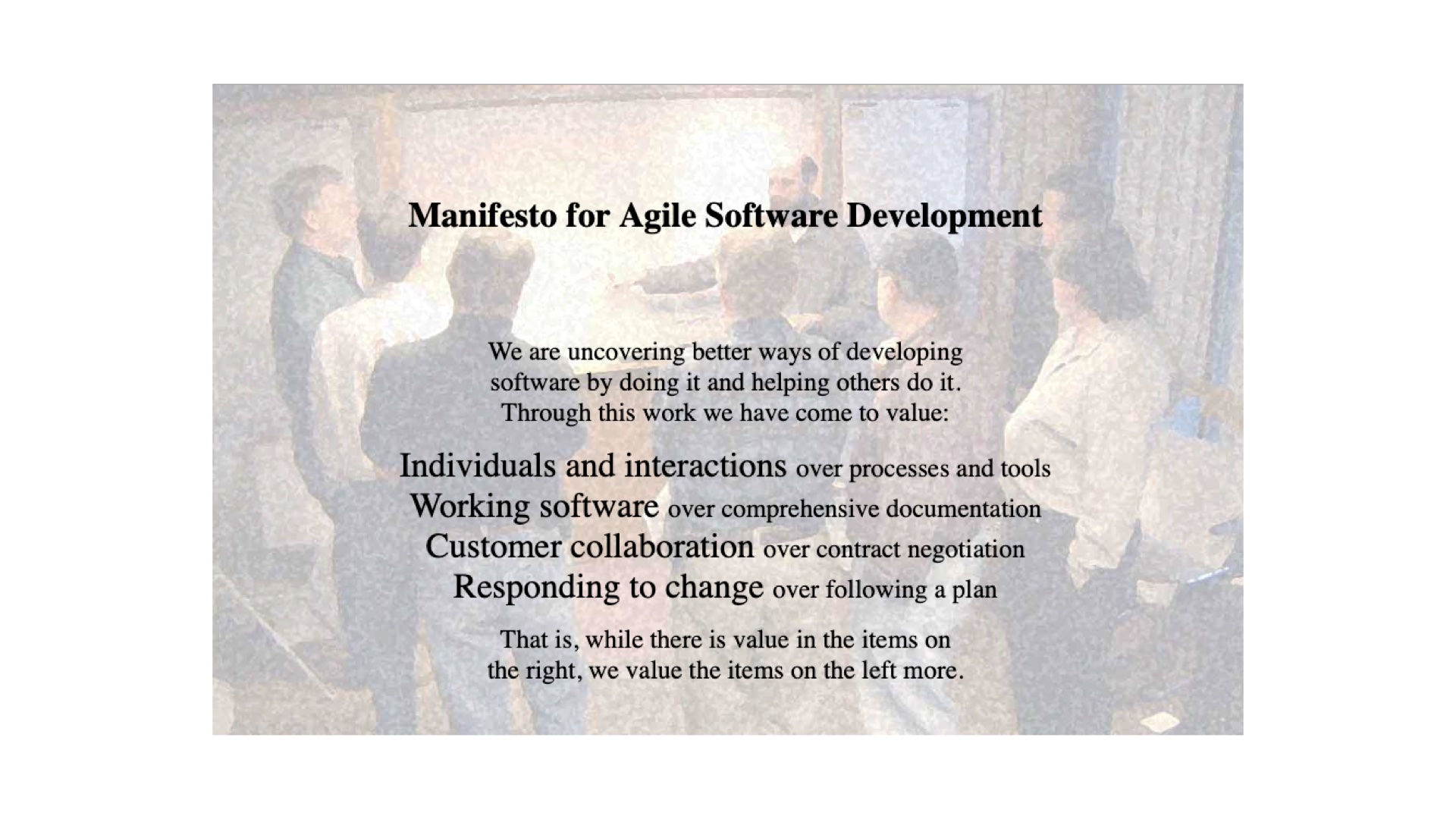

Let’s change tack now. This is the Manifesto for Agile software development. It’s a website from about 20 years ago. Now, I expect at this conference most people are going to know what Agile software development is.

But, basically, the guys who came up with the Agile Manifesto were unhappy about the way that software generally got built in the late 90’s, and wanted to throw out the big project plans and up front design and so on, and try and build software in a more collaborative, exploratory way.

This has had a massive impact on software development.

I’m going to run through a few agile practices now, really quickly, because I know everyone is just going to nod their heads to these and I want to get onto the good stuff.

There are four main statements in the manifesto here, but the one I want you to keep in mind is the first one: Individuals and Interactions over processes and tools.

So here’s a bunch of beautiful people having a stand up meeting in their office. This could well be a photo taken at Deutsche Bank in 2019. Everyone stands up to keep the meeting short. These are individuals having interactions, over processes and tools.

Now if I’m in a meeting, no one even knows if I’m standing up, or lying down. Or just a head in a jar.

The other thing about stand-up meeting is that it forced you to concentrate.

But on a conference call, or a zoom chat like this one, I might be present, but engaged in some other task on my computer.

If I’m present, but yet not present, if people are there, but not paying attention, is it really even still a meeting?

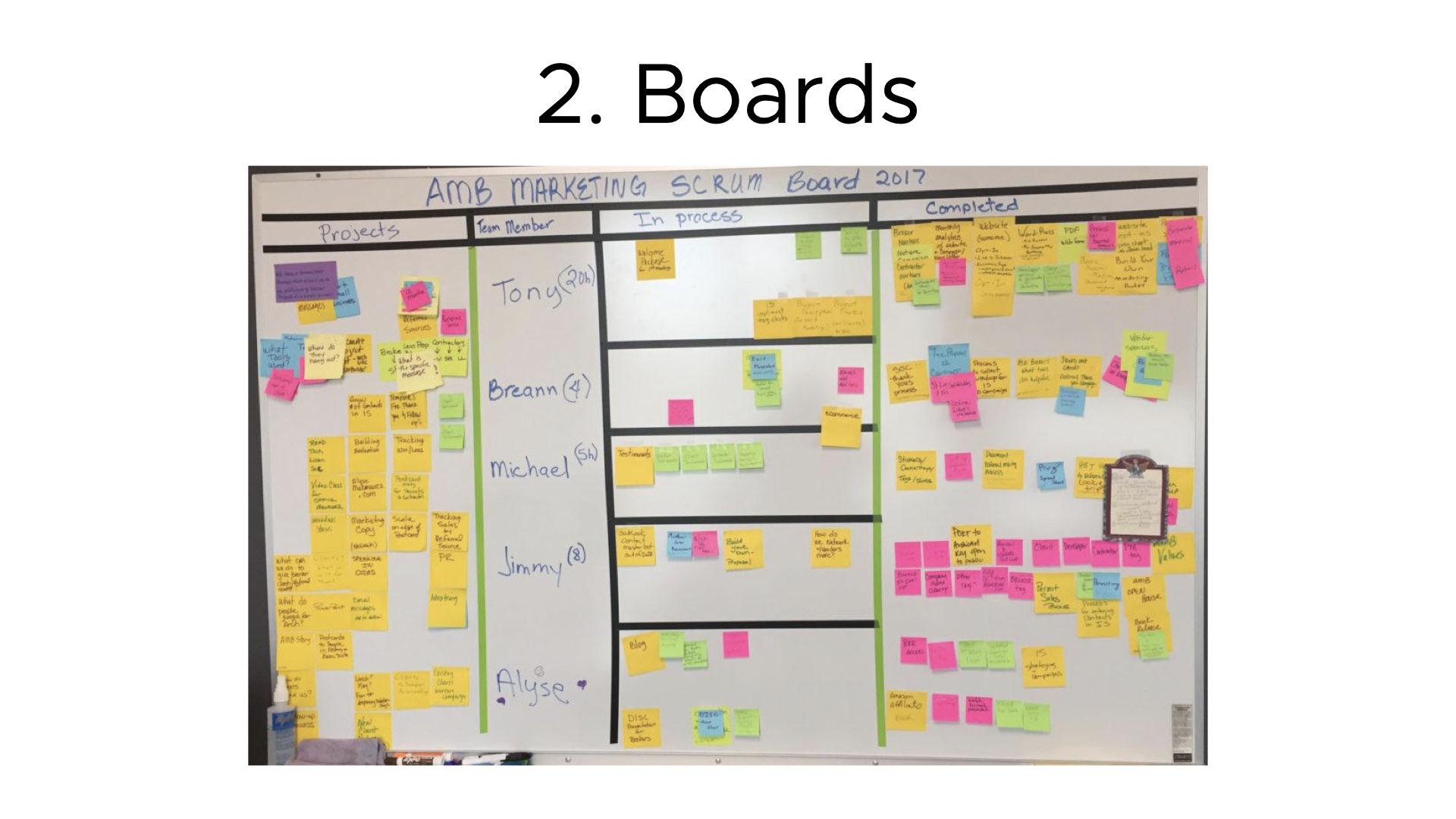

Here’s a Scrum board. It’s a bunch of post-it notes keeping track of what work is being done, and who’s doing it. This was already on the ropes before COVID, because of distributed teams. Now, it’s just impossible. There’s no way I’m devoting a wall in my house for this, and it wouldn’t help anyone else in my team even if I did.

So, we end up with tools like JIRA for tracking these things.

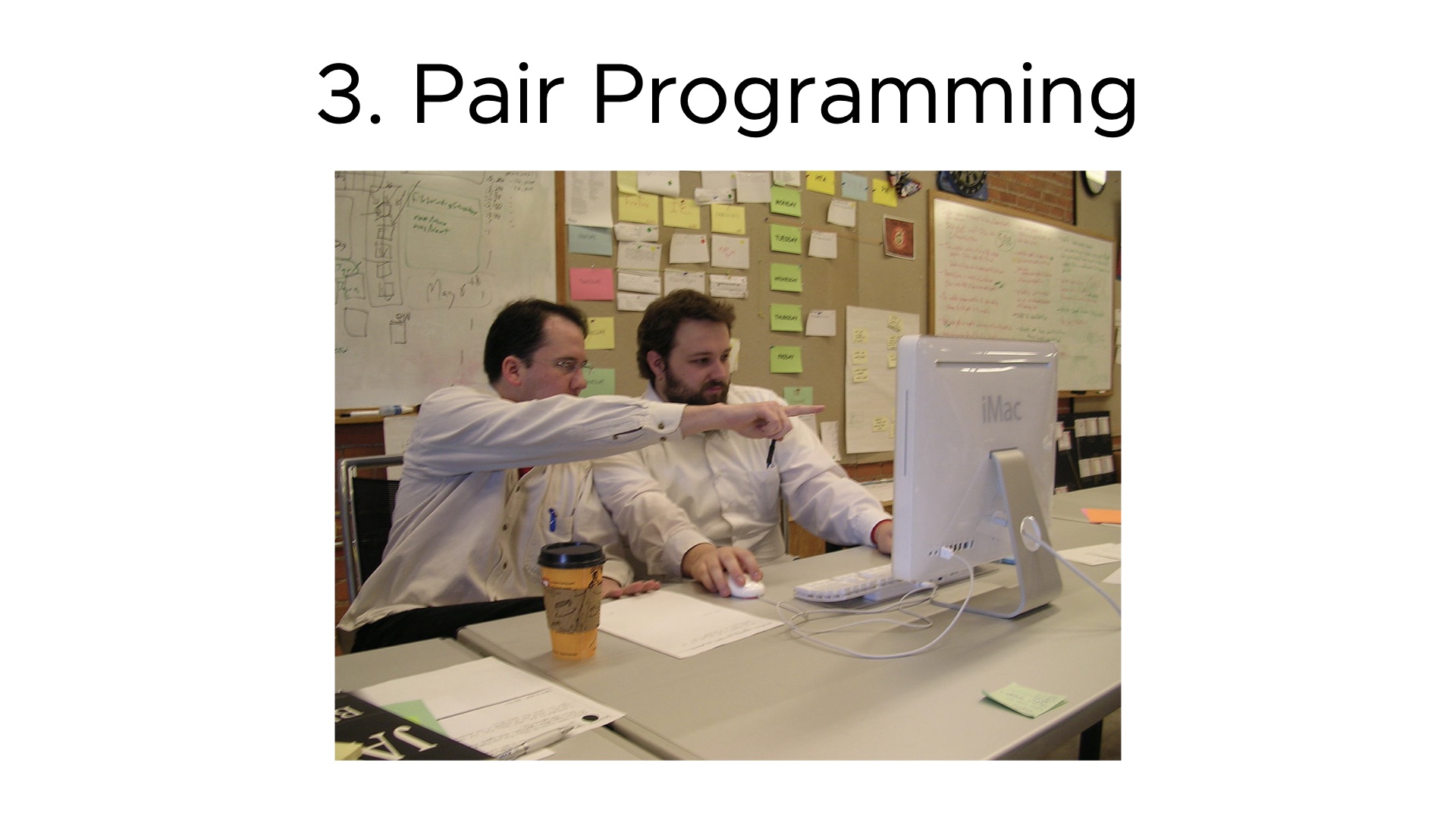

This is some guys doing some pair programming. Two people at one computer. You can see their Scrum Board in the background there. Now, this doesn’t happen anymore either. We have to screen share to get anything like this, but even then it’s not quite the same. And the tools we generally use for screen share are things like Teams, Skype, things that allow us to do chat too.

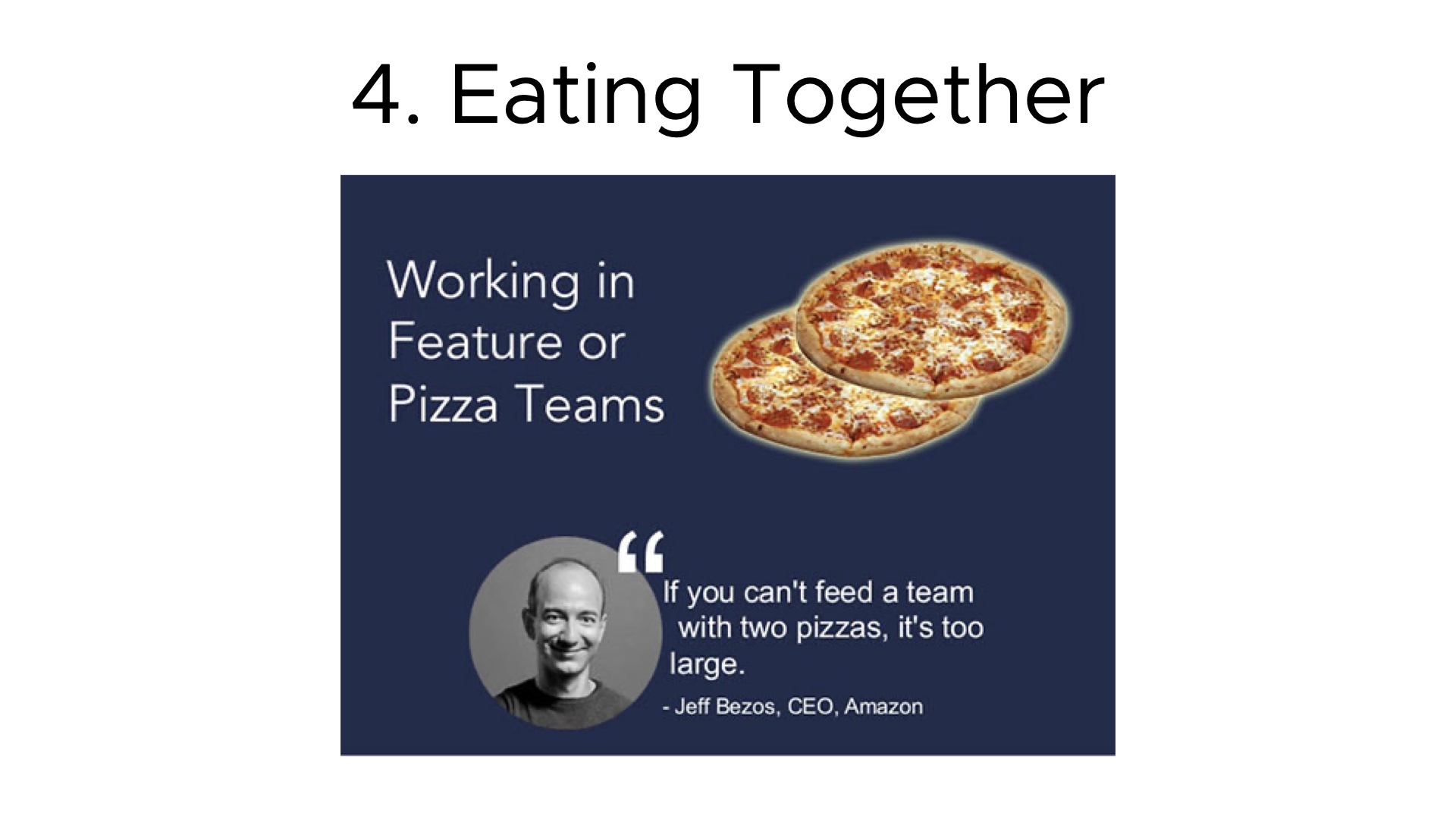

So, there is the idea of having teams big enough to feed with two pizzas. Now, this is attributed to Jeff Bezos, but I think the ideas stem from Kent Beck, who came up with an Agile approach called XP, or Extreme Programming. He was very keen on his developers all eating together, and working in close proximity to each other so they could discuss their issues over a donut or a coffee.

I don’t know about you, but the people I work most closely with, I’ve never even met physically. They’re in India.

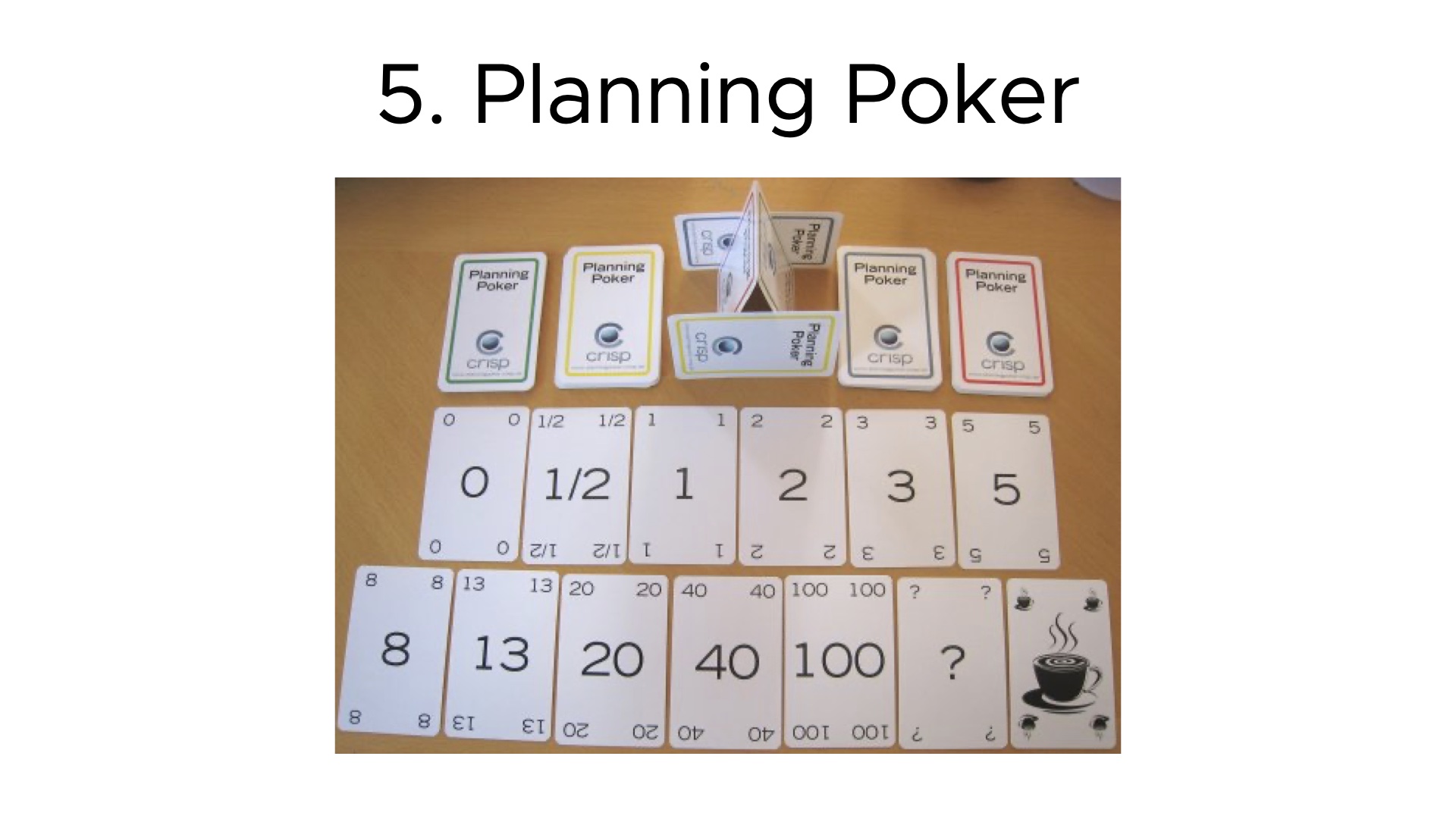

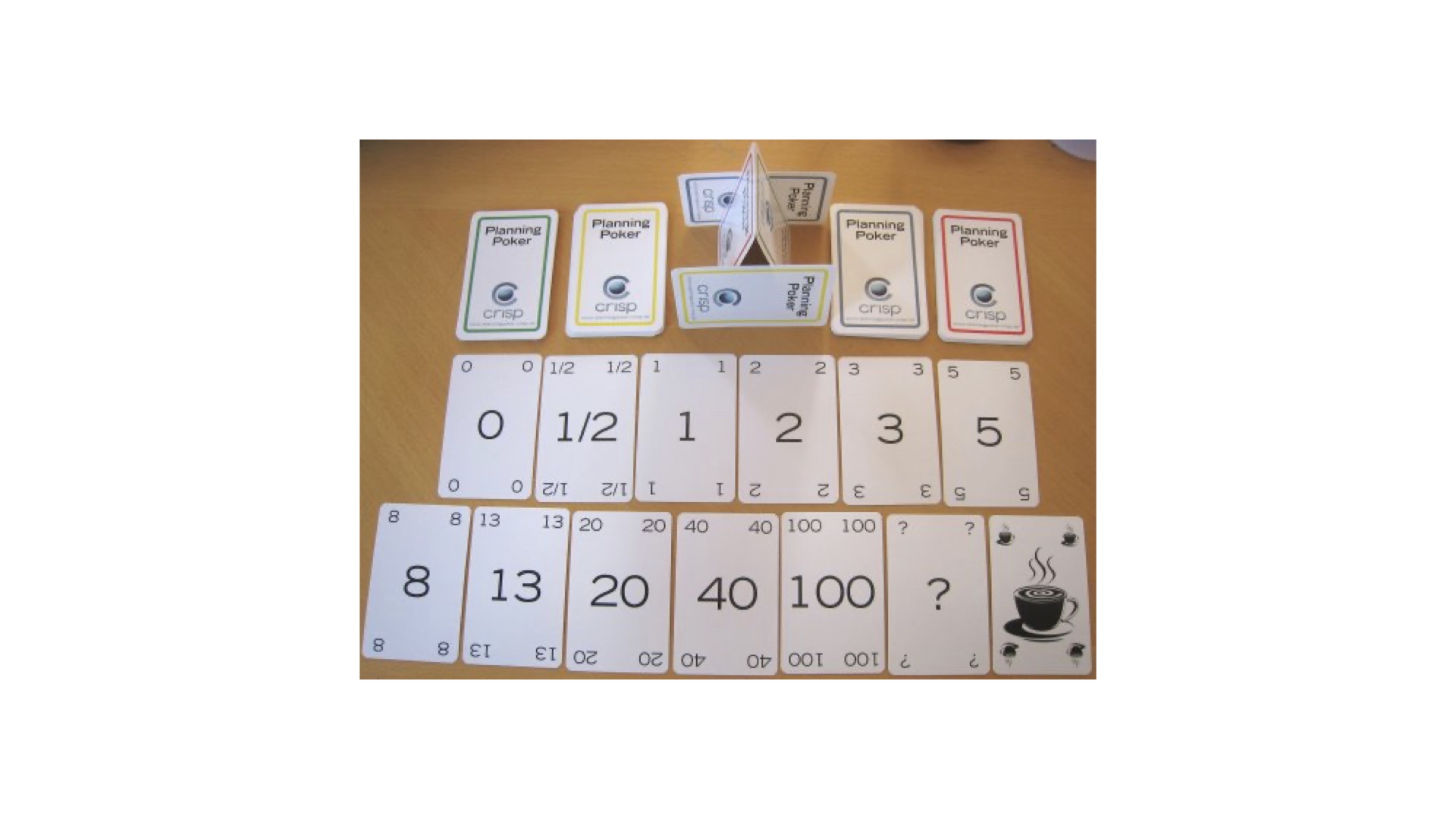

Finally, this is Planning Poker, from Scrum. The idea is that when you are planning what work to do, everyone plays cards. The higher the number card you play, the more complex you think the piece of work is.

The idea is that everyone in the team will eventually agree on the complexity of a piece of work.

The reason you’re doing this with cards is to stop peer-pressure and group-think: you don’t want the first person’s estimate to affect the last persons’. So you all play your cards at the same time, and then discuss why they’re different.

Again. Cards, Tables, face-to-face discussion. Gone.

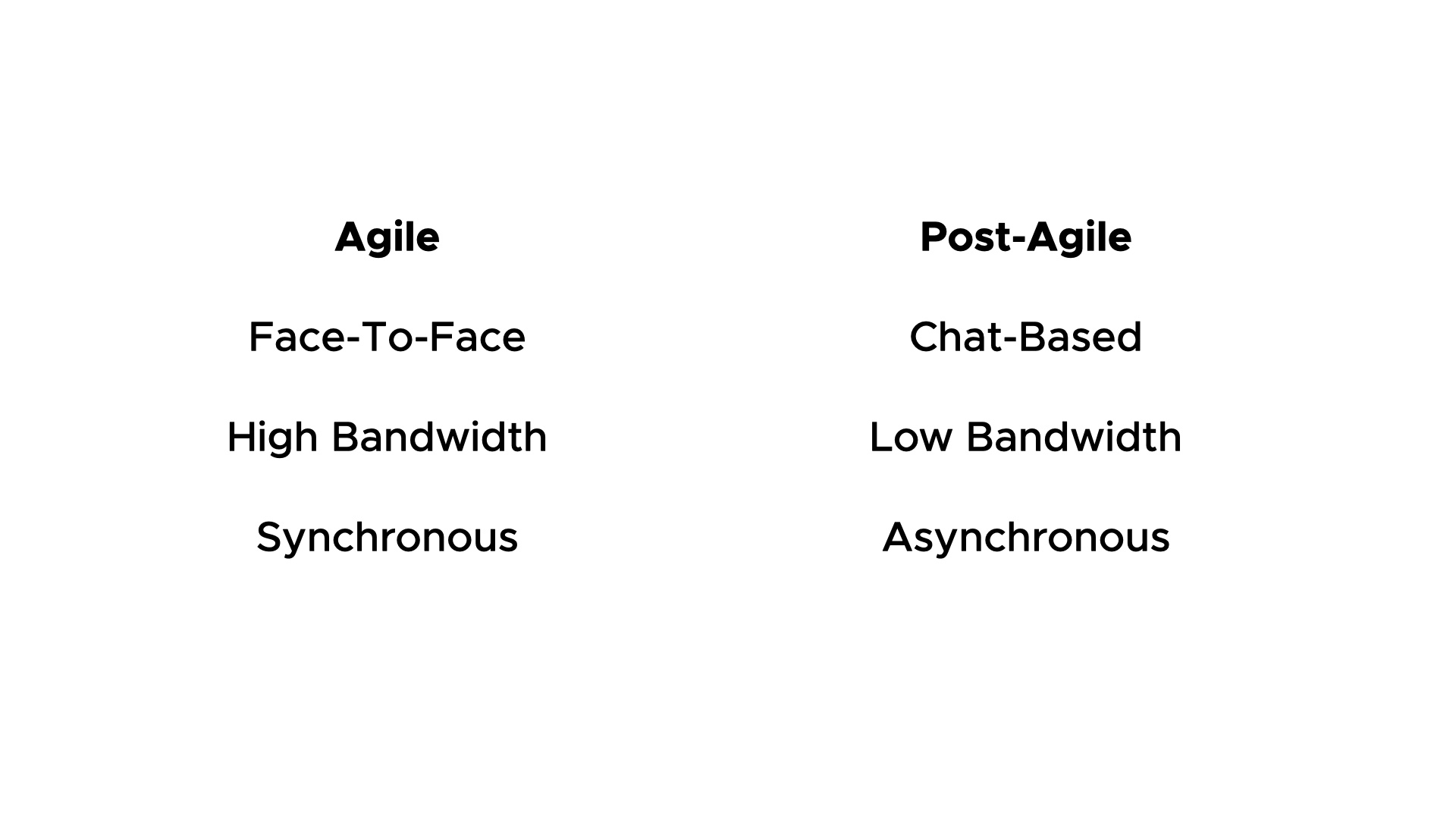

This is that first statement from the Agile Manifesto again: Individuals and Interactions over Processes and Tools.

So, it’s now apparent that now, and certainly for a while, you can’t do Individuals and Interactions without chat and phones and video-conference tools. We need those tools. It’s not a choice of this over that, as the Agile Manifesto had it. It’s literally, you can’t have the thing on the left, without the thing on the right.

It should be Individuals and Interactions via Processes and Tools.

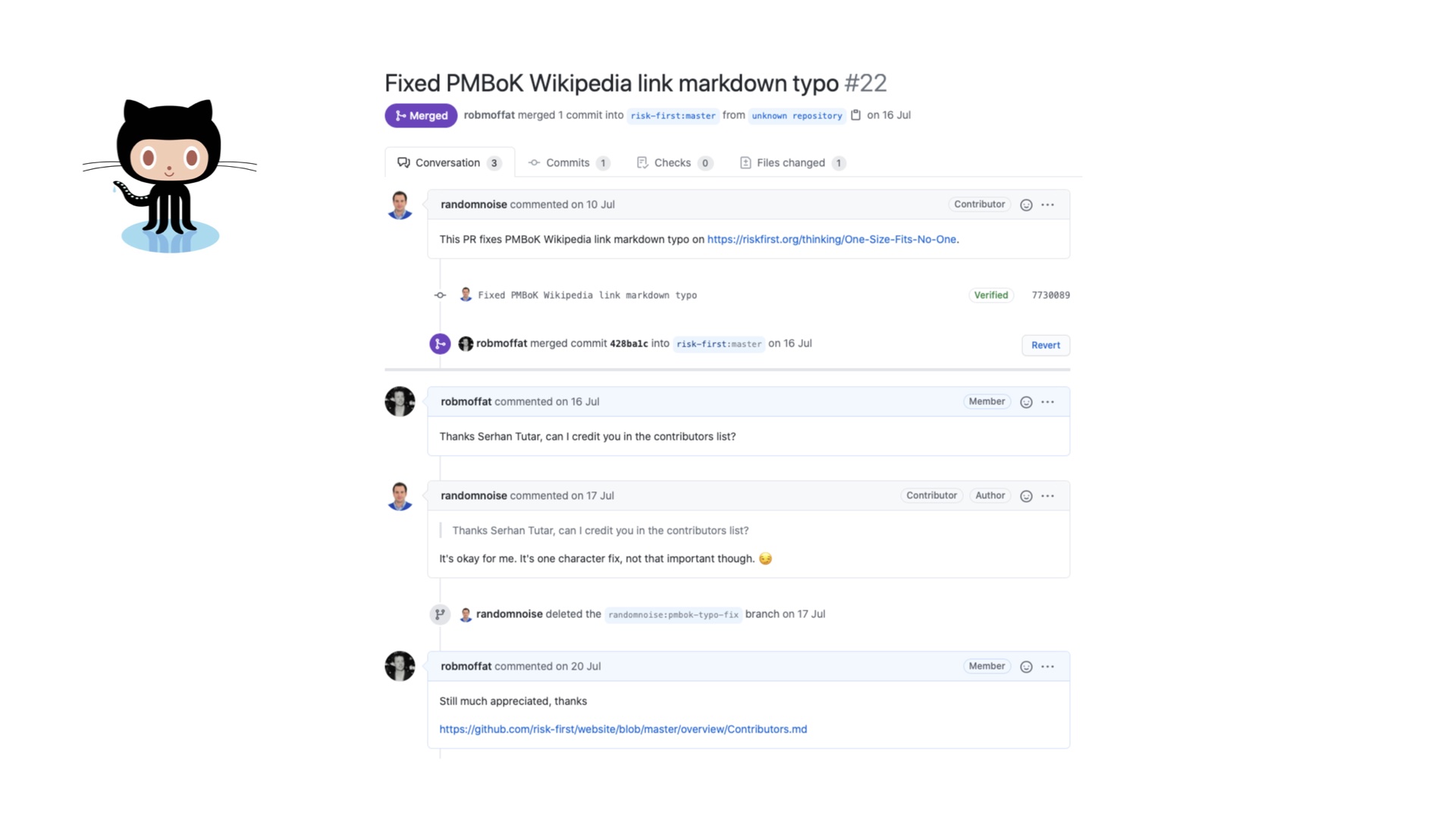

But luckily, there are teams that have been working like that for a while now. On GitHub, like a lot of other people, I contribute to software projects, and rather than coordinate with people using the Agile approaches I’ve discussed, we coordinate with chat.

Here’s an example where someone on the internet contributed a minor fix for an article I wrote on GitHub. They opened the issue, submitted a Pull Request, which I reviewed and merged.

GitHub works really well like this.

So, COVID is really forcing us to move away from those traditional Agile practices. A while ago, whether or not you prefer one approach over the other was personal style.

But now that’s kind of irrelevant - you have to make the change.

Let’s talk a bit about ChatOps now.

In previous presentations, I’ve thrown up the definition of ChatOps, and it’s got a lot of people scratching their heads, and maybe not really understanding the full impact of it.

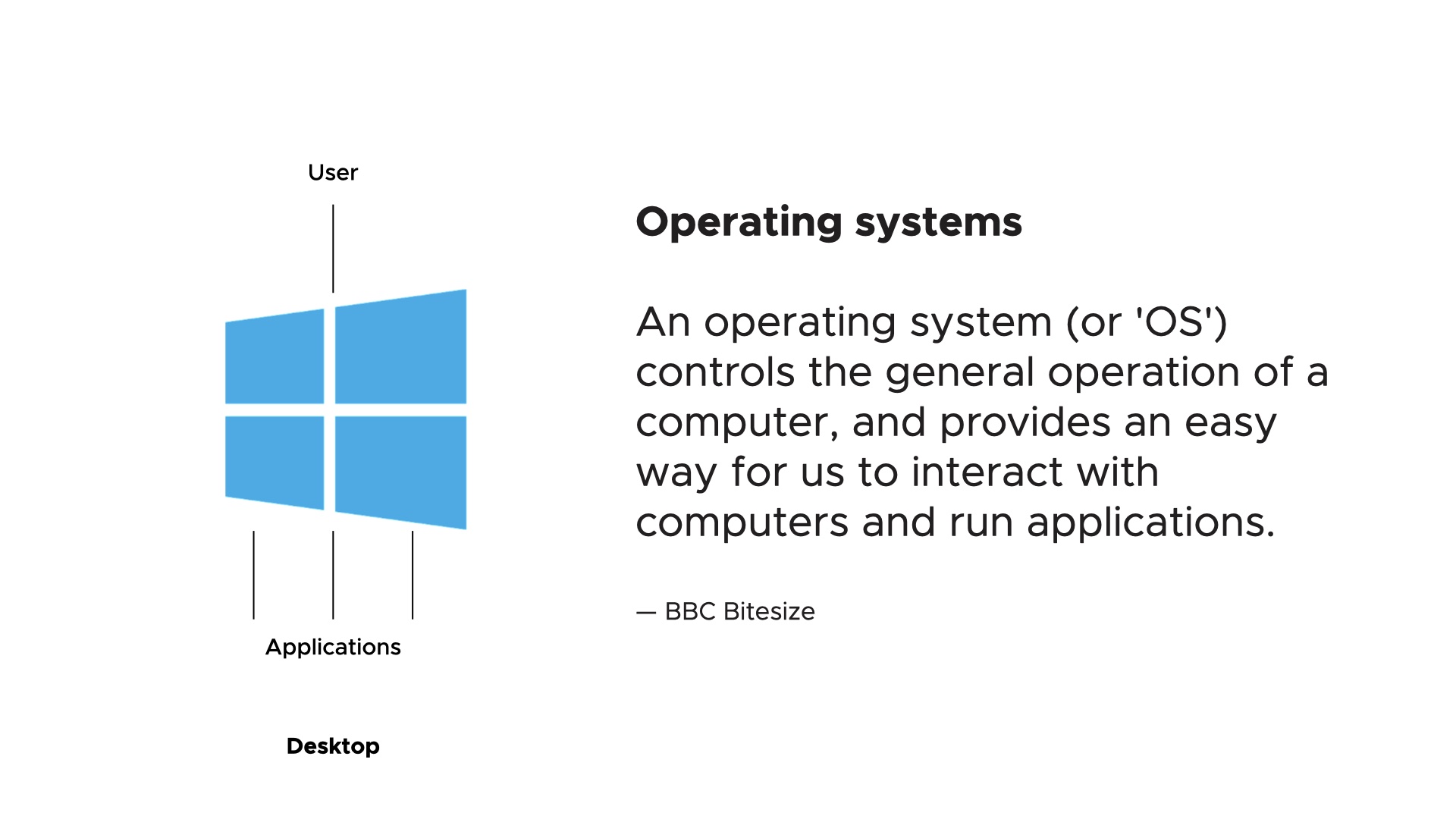

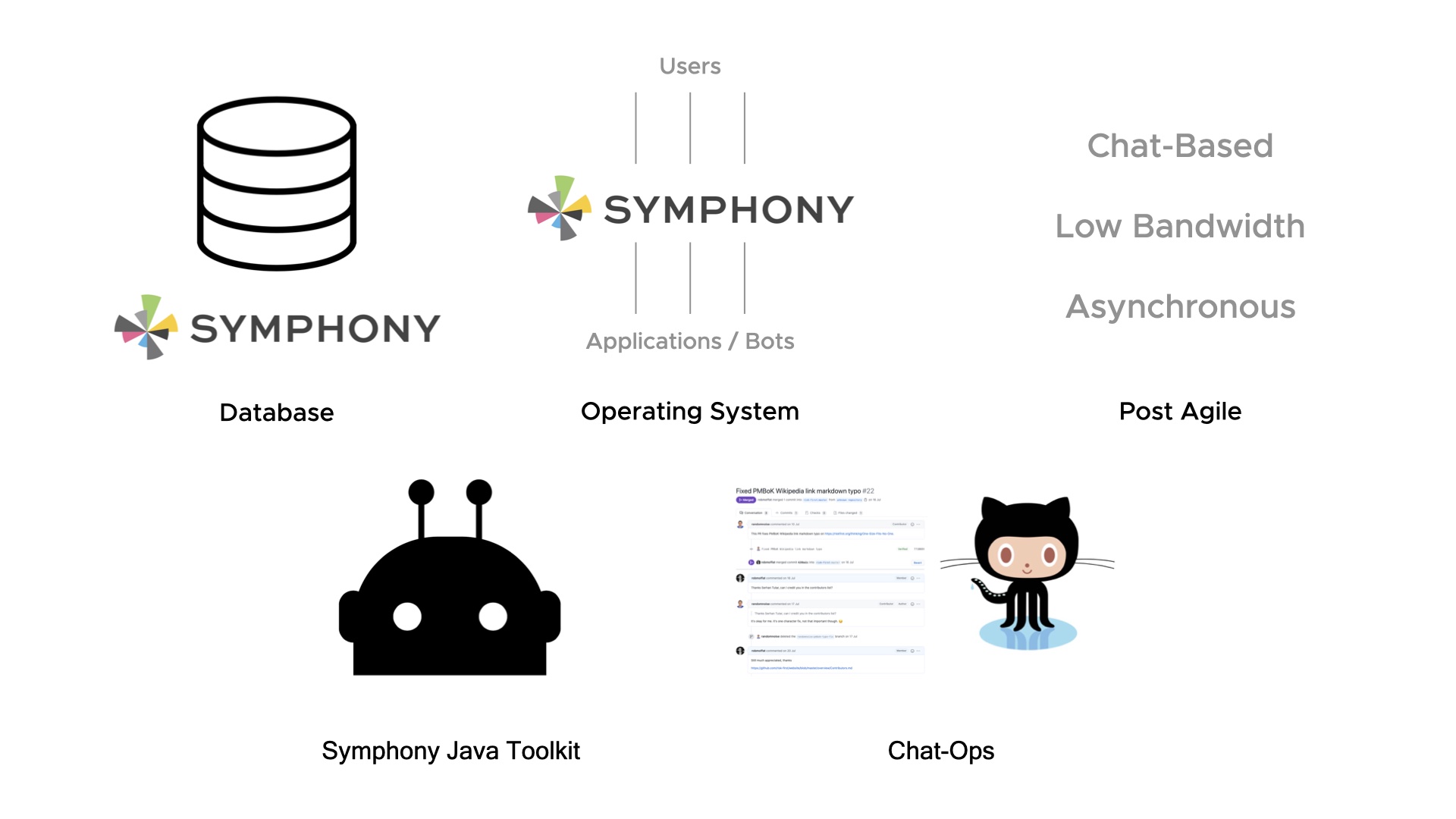

So, I’m going to come at it from a different direction here. First, let’s ask the question: What is an Operating System?

Well, according to BBC Bitesize, which is a part of the BBC for helping school children revise for their exams, “An operating system (or 'OS') controls the general operation of a computer, and provides an easy way for us to interact with computers and run applications.”

The reason I chose this definition is because it’s one of the only ones that mentions us. An OS provides us an easy way to interact with our computers. And, do the stuff we want our computers to do: printing, editing spreadsheets, and so on.

On the desktop, the dominant Operating System is Microsoft Windows. It is mediating the interactions between you, some software applications, and the hardware.

On Mobile, the dominant operating systems are iOS and Android. Microsoft did try to have a Windows version for Mobile, but that didn’t really work out. The types of things we do on our phones and tablets are different to the things we do on the desktop, so perhaps that’s one reason why we ended up with different operating systems there.

The underlying hardware is also different, so the Operating System is doing different things. And the applications, a lot of the time, are different too.

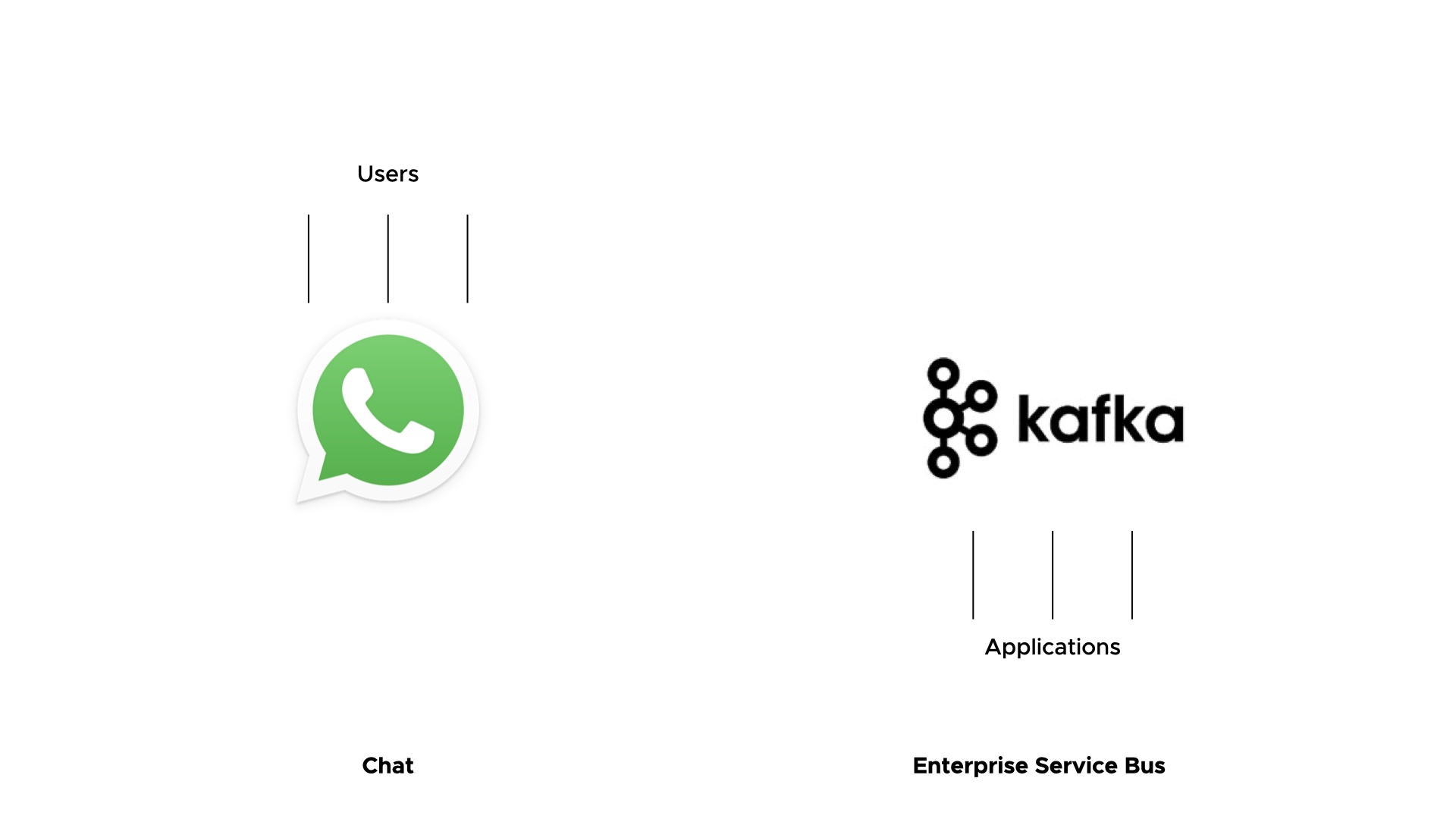

Now, here’s a couple of other things that could claim to be a bit like that definition of Operating System.

Things like Skype, or WhatsApp, here, mediate the interactions with lots of other people, rather than applications.

And something like Apache Kafka, which is an enterprise service bus, is mediating the interactions just between lots of applications.

So ChatOps essentially, is the chat platform as some kind of operating system: lots of users, lots of applications, all working together. Let’s look at an example.

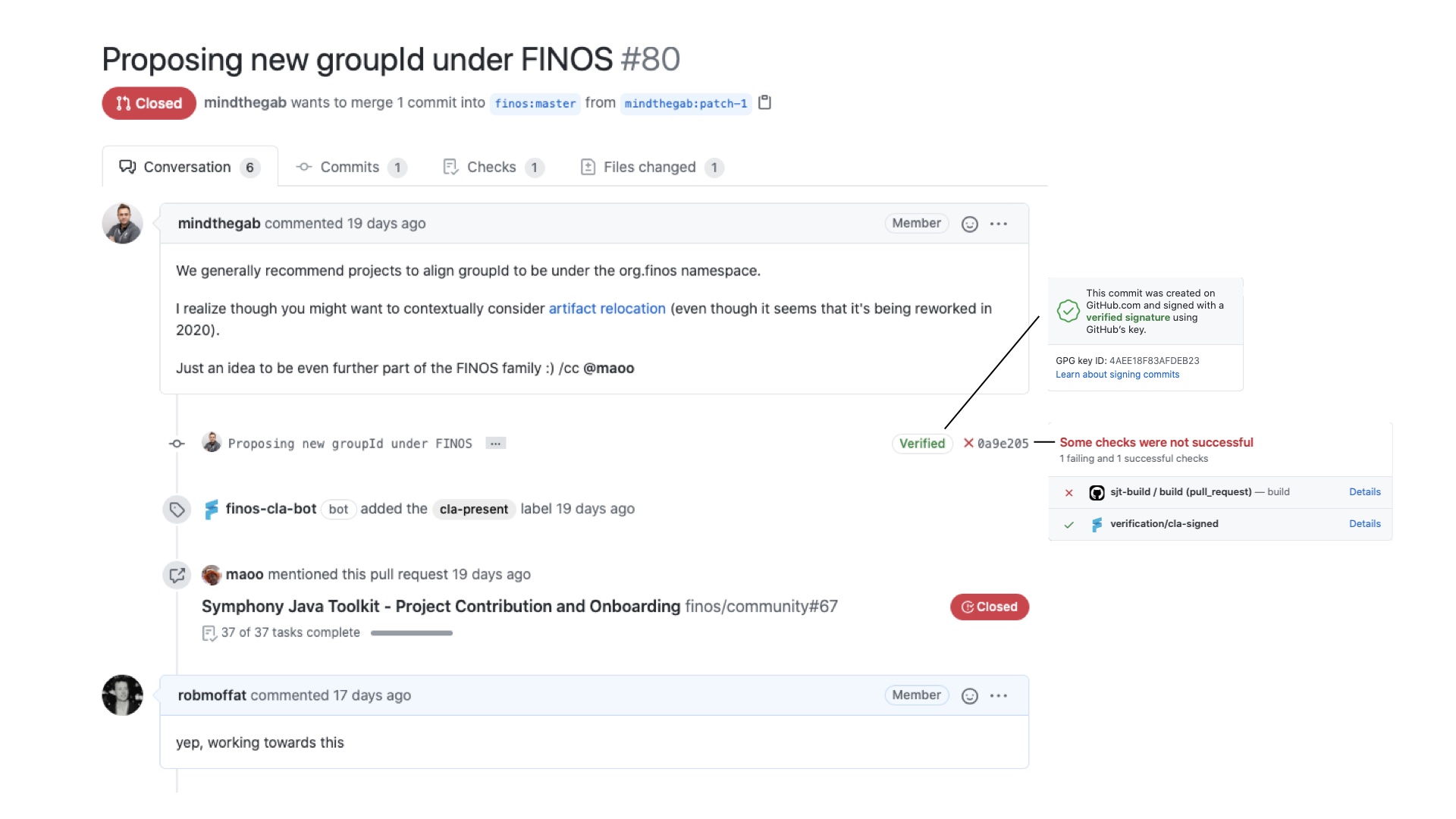

For this, I’m going to show an issue from our GitHub project, Symphony Java Toolkit.

So, in this issue, Gab raises an issue suggesting changing the namespace. He’s cc’ing Mao, with the “at”.

On the next line, you can see a “verified” badge there, which says that Gab’s commit was verified. Next to that you can see a red “X”, which shows that as a result of the commit: a build has run, and failed.

Additionally, you can see the “finos-cla-bot” has added a tag, “cla-present”.

Mao mentions this issue somewhere else, and I comment on it.

This is a workflow involving people, and applications. Although in this context, we call them bots for some reason.

GitHub have arguably achieved a type of Operating System, designed to allow people and applications to collaborate to build software.

Whereas Windows was an operating system about, well, Windows, and people, and a mouse, and on-screen buttons, GitHub is an Operating System about chats, repos, bots and users.

This slide says it all: “Teams is the new operating system, essentially, for a customer. It is where they will do everything that they need to do.”

This is Microsoft Saying this. Microsoft gets this. They want to re-create the glory days of Windows so much that they bought GitHub. They own it. And, they’re also throwing everything at Teams.

So where are we so far: Well, one, there’s a new kind of Operating System that hosts our applications. Two, COVID has forced us into a different way of working. And three, old Agile practices don’t hold any more.

So, if that’s the case, then we need to build our applications to suit this new working environment.

I have been developing Bots and Apps on Symphony for a number of years, both at HSBC and Deutsche Bank.

Since being at Deutsche Bank, we’ve put together the Symphony Java Toolkit. And, recently, we’ve donated this to FINOS to own and market doing forward. It is an open-source collection of libraries, available on GitHub that you can use to build Symphony bots.

But to frame this work, I want to take you through the evolution of our thinking with respect to building bots, and through that arrive at the reason why we’ve build this toolkit.

So, to start with, my view of bots was “Oh, it’s the command line all over again”. I can type commands to my bot, and have it respond. Text in, text out, just like DOS or Linux.

Although that’s limiting, it’s also liberating: I don’t have to worry about authenticating the user, I don’t have to worry about testing in different browsers, worry about networks, or firewalls, or accessibility, or keeping up to date with the latest fad Javascript libraries.

So, that seemed nice, but, at the same time, much more limited than building a web app, say.

We’ve also seen a lot of times, bots being used for things they shouldn’t be. It seems like every website has a bot these days. They’re victims of the Hype Cycle.

But there are use-cases that work better on a chat platform.

The first is, anything to do with notifications. That works much better here than on a web application, because generally, people will always have their chat application open.

It’s probably a better way to receive a notification than via email, if the notification is something short. The chat platform doesn’t replace a Wiki or a content management system, but it’s great to notify people of things. Also, it’s great for persistence: all your messages are recorded for all time, and searchable.

And obviously, a chat platform is way better than a browser app for for sharing things between groups of people, because all of those abstractions are provided for you around identity, rooms, groups, messages and so on.

So, there are good reasons for building bots.

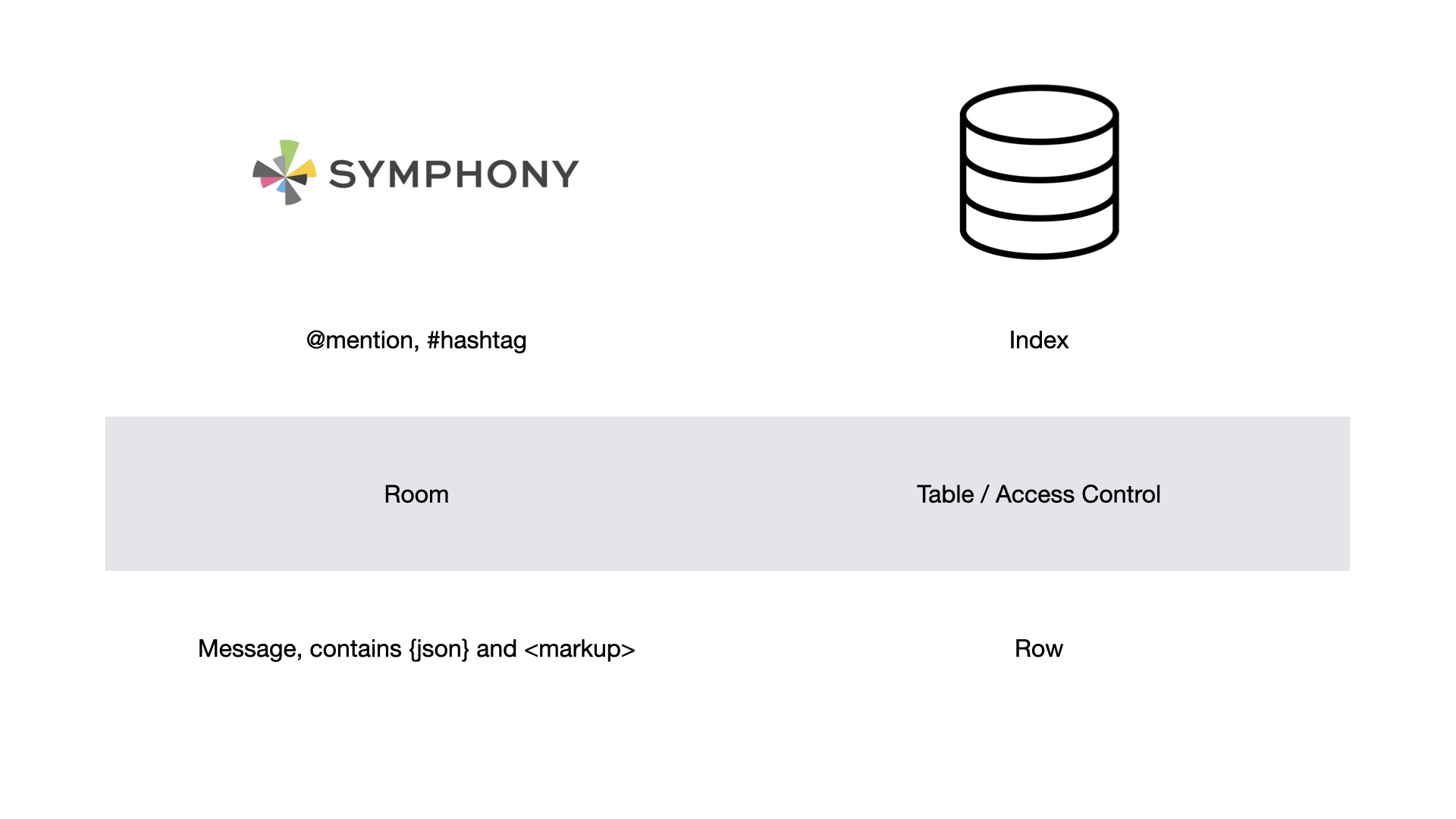

Next, I started to see that a Chat Platform was really a lot like a big append-only database, like Datomic, say. You can do indexing, through hash-tagging and mentions, and you can control access to different pieces of information via Private Chat Rooms, since different rooms can have different members and privacy settings and administrators.

Each message on Symphony (and this is true on Teams and Slack too) can have a JSON payload, as well as some markup formatting of the message. That means that chat is perfect for storing the details of a workflow, as we saw in the GitHub examples.

So, rather than do a tour of the functionality in the Symphony Java Toolkit, I’m just going to demonstrate something we built with it, and show you how it works.

A lot of the stuff I’m building at Deutsche Bank is behind our firewall, and so, I can’t show you any of that.

But just a week ago, the DB Symphony Practice participated in Symphony’s yearly London Hackathon.

Now, as you’d expect, this was done remotely. We were actually all sitting at home, chatting about what we were going to build (using Symphony, obviously). We were video-conferencing and screen sharing. But actually, this was a plus. As I’ve said earlier - my team are based in India, so if we’d had a physical Hackathon in London, well, it would have been a different story.

My team wouldn’t have been able to get involved.

But this just further underlines the point about the changing nature of development work that I made earlier.

So, we now had to choose something to build for the Symphony Hackathon, and, probably somewhat fortuitously, it ties together all of the things I’ve been talking about so far. I hope.

We’ve talked about: Symphony as being like an append-only database, which handles access control, and indexing.

We’ve talked about chat as being like a new kind of Operating System, linking people and bots and allowing them all to work together.

We’ve talked about the effect of COVID on Agile, and how a lot of the practices of Agile don’t work anymore.

And, the Hackathon gives us a great chance to test out how quickly we can build something with the Symphony Java Toolkit.

So, what did we build? OK, well remember we only had an eight-hour working day to build something, so, it’s not going to change the world.

But hopefully it will give you an idea of how the Symphony Java Toolkit works.

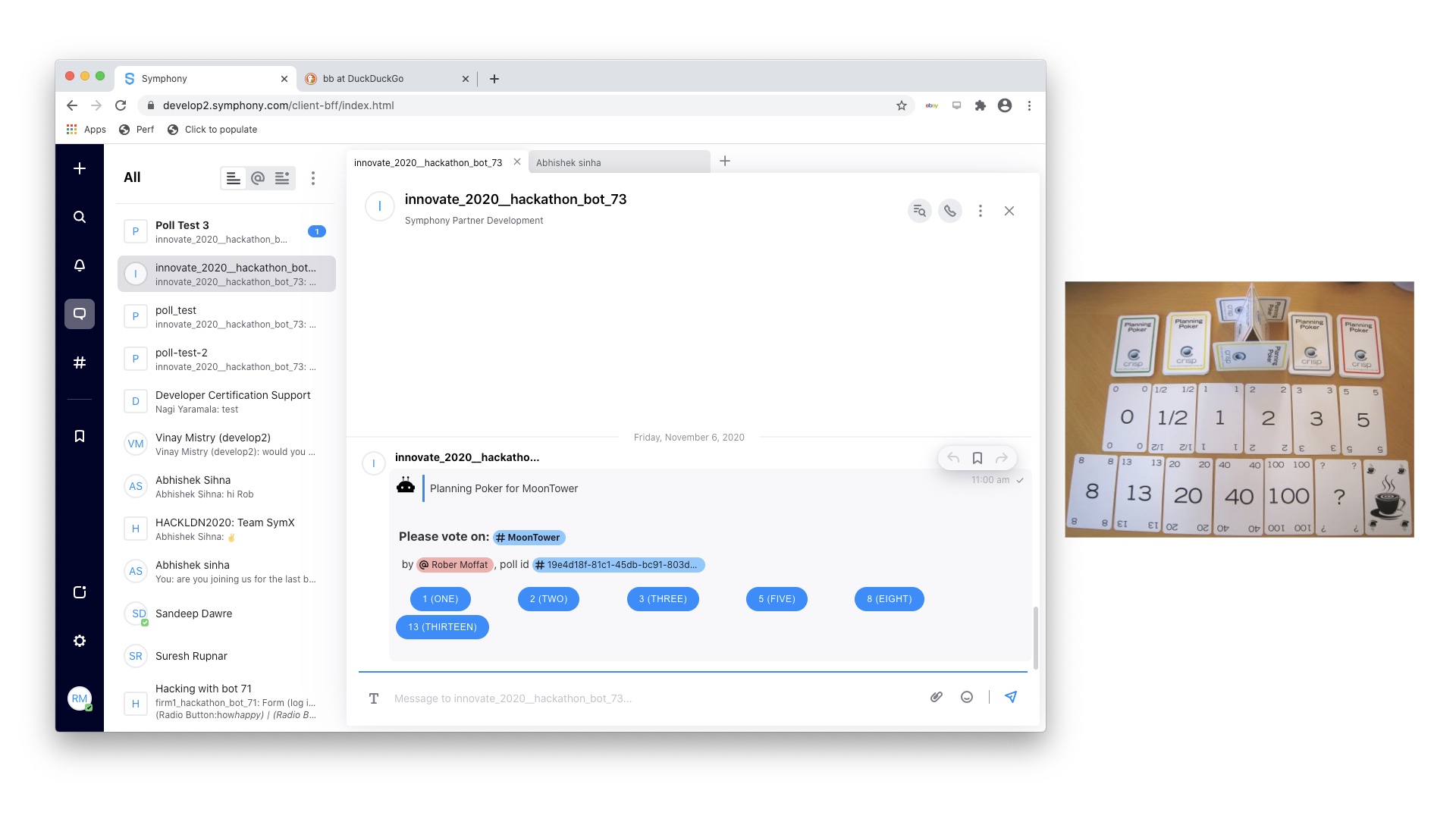

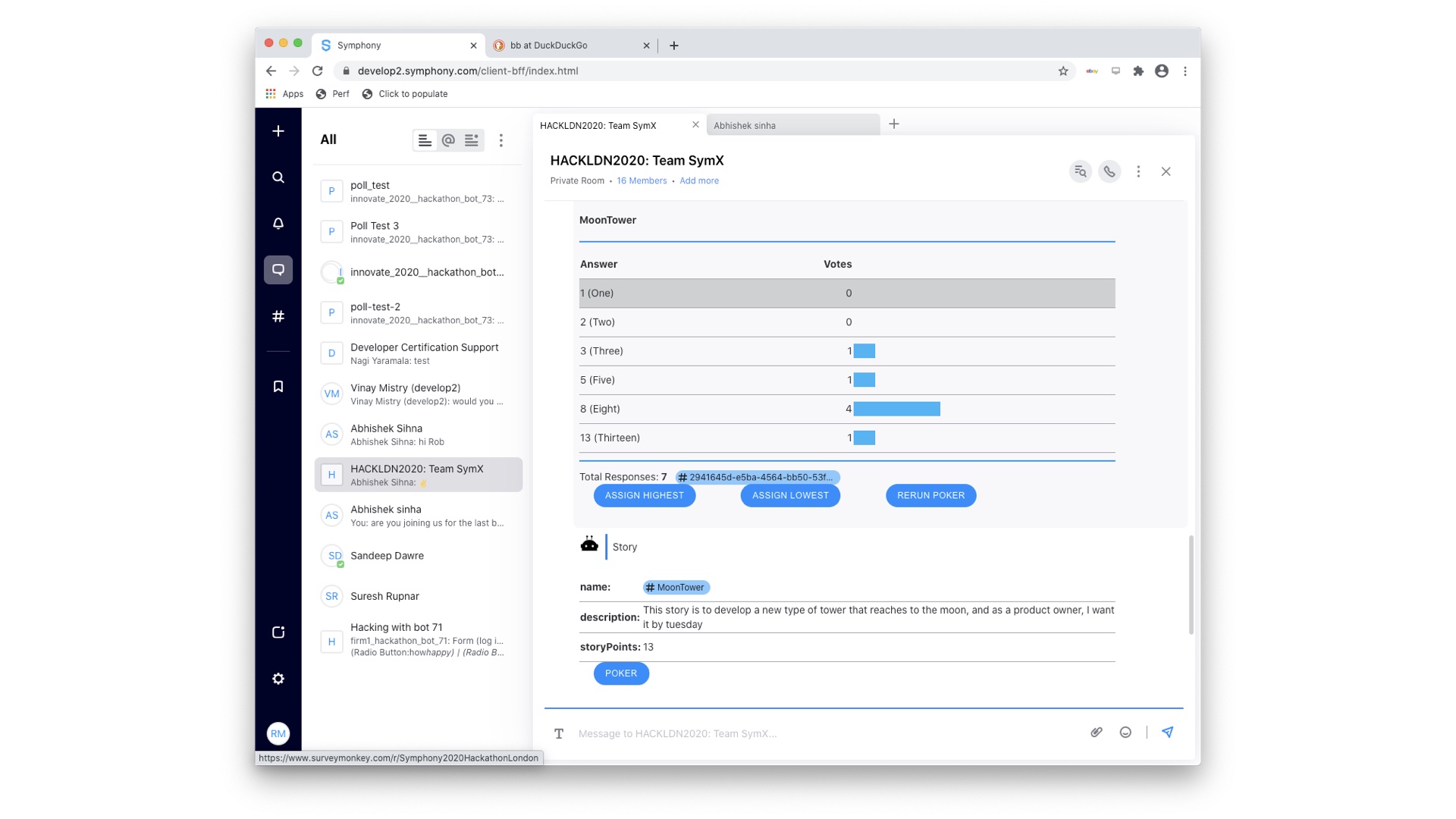

We built a Symphony Bot that allows you to play the Scrum planning Poker Game… via a Symphony Chat.

So, remember back to how I described this earlier: people get together, and play cards (face down), to try and indicate their complexity estimates for a task. Then, everyone reveals those estimates and shows you the results.

Now, I’d like to do you a live demo, but unfortunately, at the time of recording this, all my colleagues are very asleep, so instead I’m going to replay the demo we gave in the hackathon as a set of slides… and yeah that also reduces the chance of a technical disaster too, so sure, you can call that a cop-out, but I hope you get the idea of what’s going on anyway.

I’ll be using screenshots of Symphony to illustrate my points.

At the same time, I’ll talk about how the Symphony Java Toolkit allows us to build these things at hackathon speeds.

Just as a trigger warning going in, there will be some screenshots of Java code - I’ll be talking about them at a high level, but there will be no need to comprehend what the code is doing.

So, instead of getting our developers together in a meeting room, we’re going to get our team together in a Symphony room, to play the planning poker.

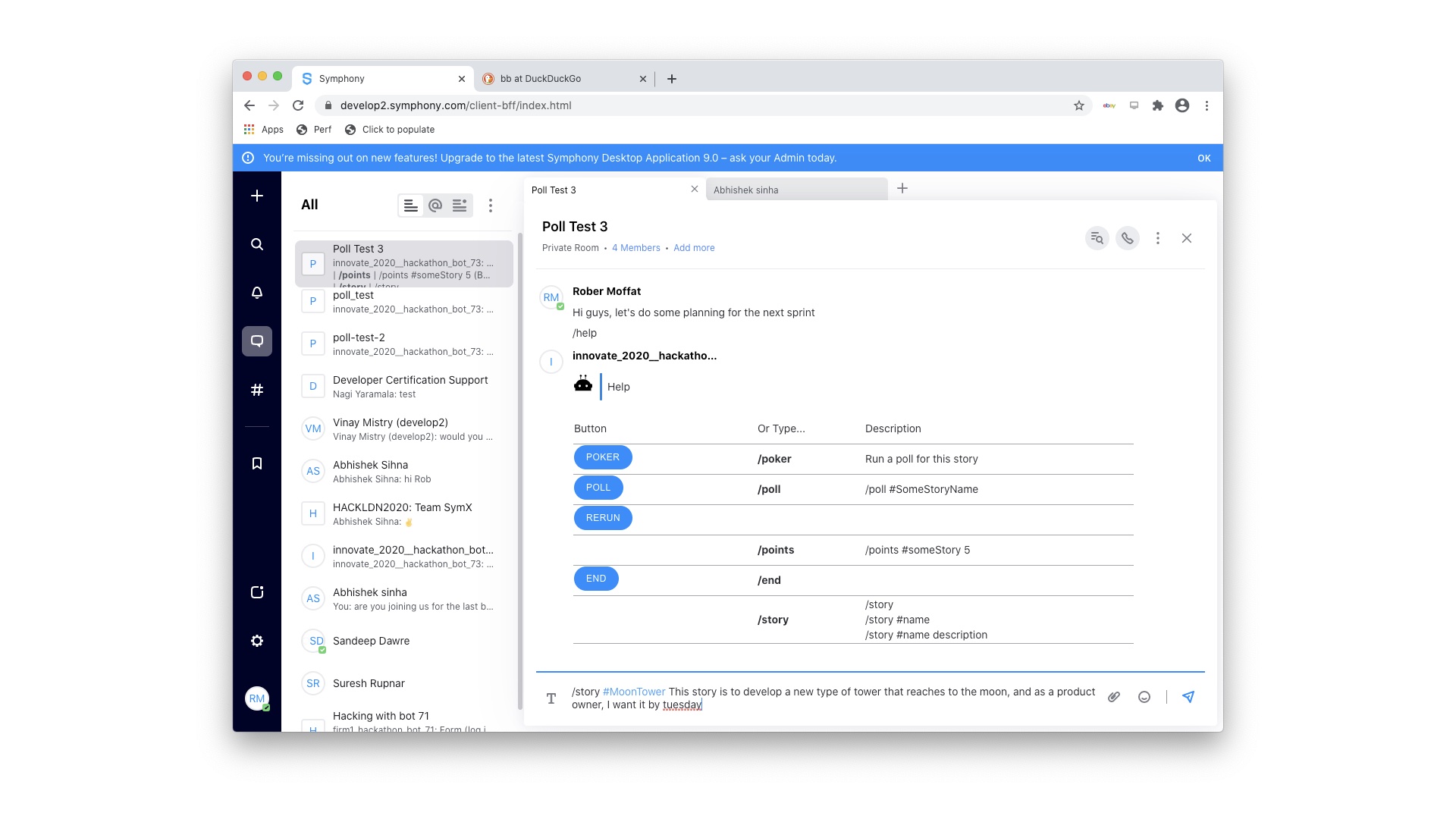

On this first screen, I’ve typed /help. Often, when you want to address a command to a bot, you put a slash in front of the word, so that people know it’s for the bot.

Everyone in the room gets to see this same help message.

And symphony allows you to embed form elements into a chat, so you can have buttons like these blue ones that people can press to tell the bot to do things. And we’re going to use those later.

So, first up, in Planning Poker, someone proposes a story to vote on. So, at the bottom, I’m typing in the details of the story. Now, to identify the story, we’re using a hash tag. So, people can refer to that story by using the #MoonTower hash tag. And, as I said before, hashtags are a kind of index. In Symphony I can also “watch” tags, and get notifications each time they’re used.

So, the rest of that line is the description of the story, for the other developers to think about. Then I hit enter, and this happens.

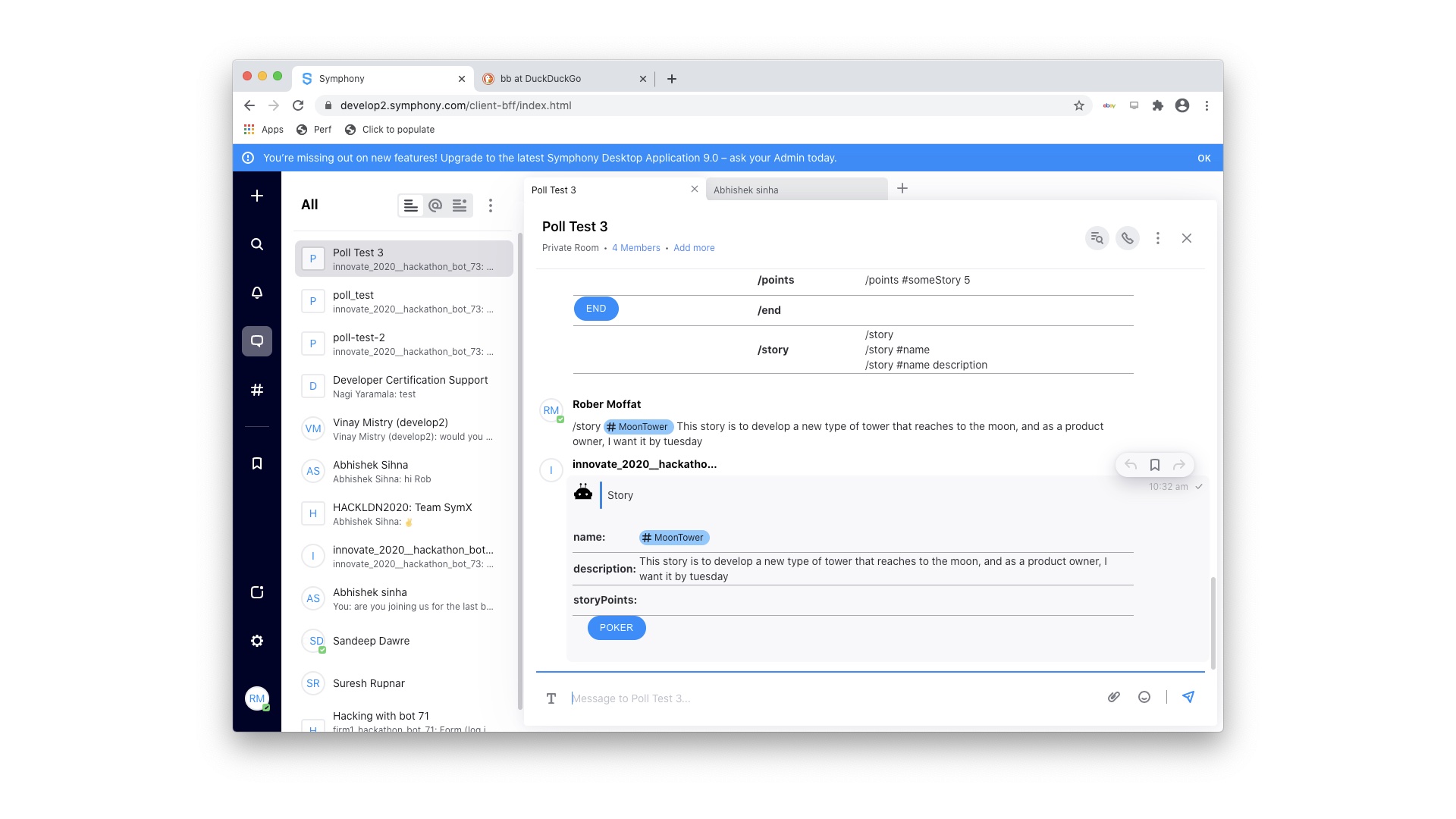

The bot replies back with this card containing the story. It’s got a name, a description and an empty story points field.

Now, remember back to our database metaphor - this is something like adding a new row to the story table in the database. And, as I said before, although there is markup on the screen here to display the story, there’s also a JSON representation of this story, that Symphony, and our bot, understand.

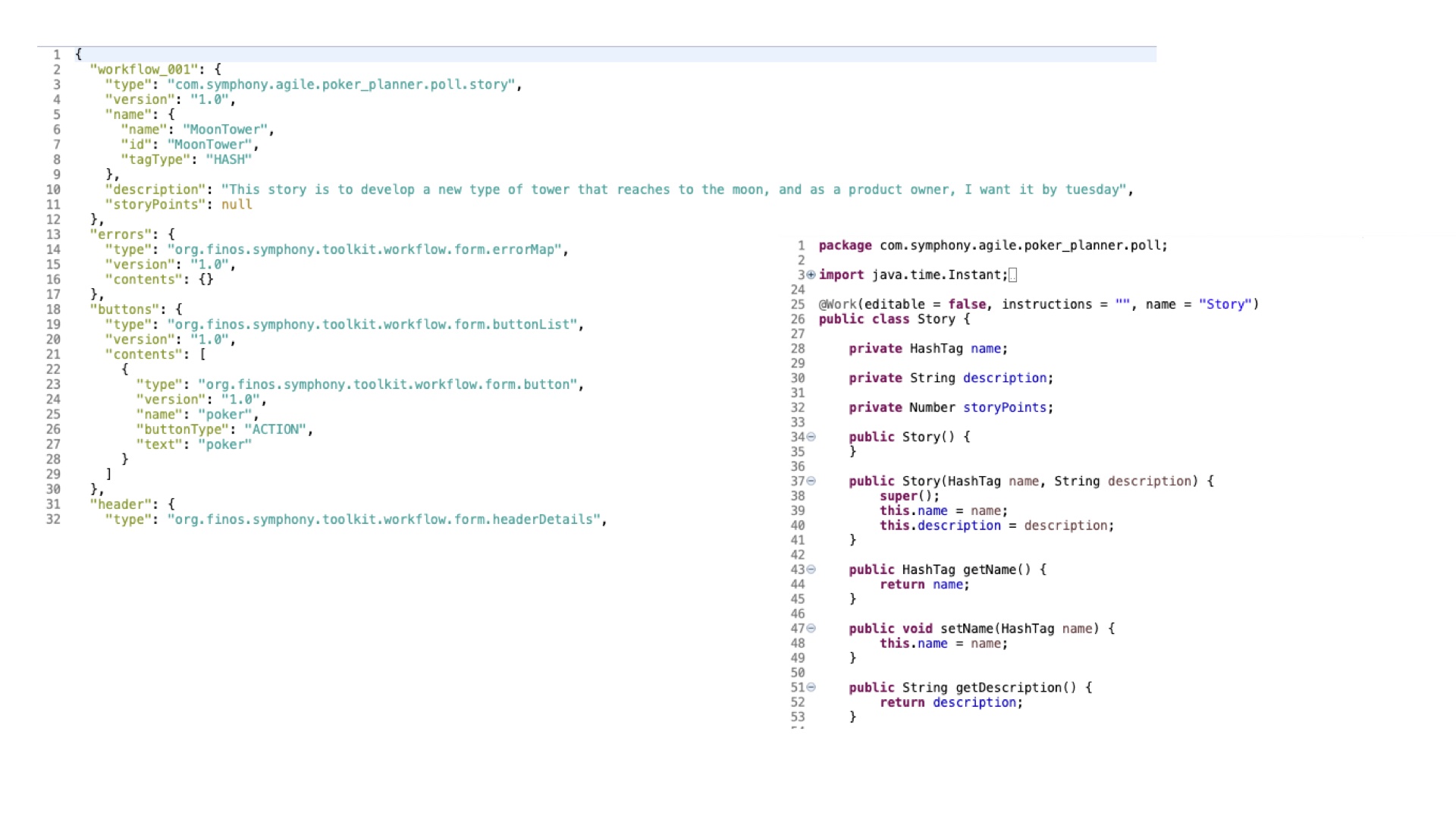

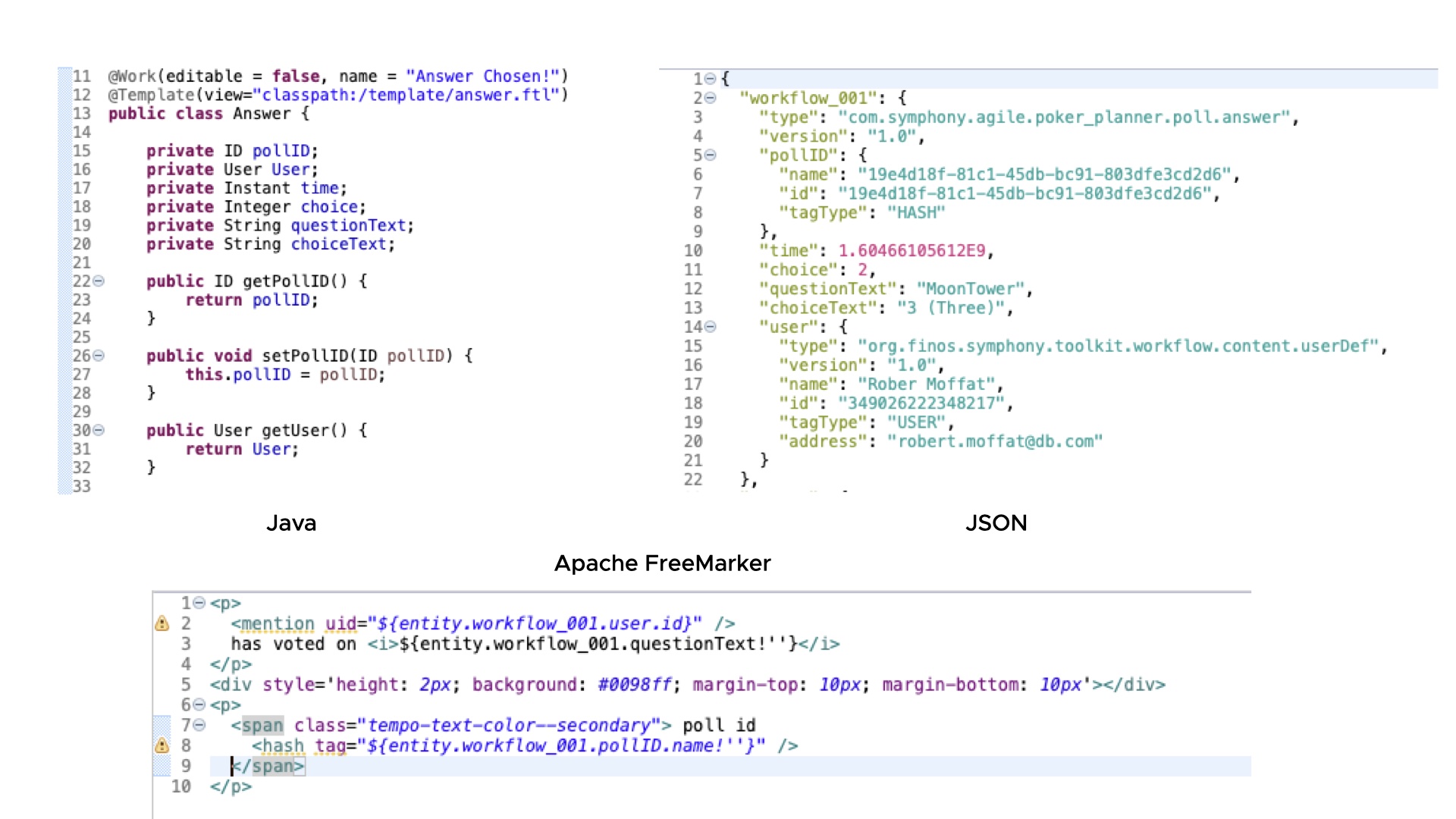

So this is on the left is what that underlying JSON looks like: that workflow_001 is the main bit. It’s got the name and the description, and the empty story points field.

And on the right, this is the Java representation of that story. You can see it has fields for the name as a hash tag, the description and the story points.

The Symphony Java Toolkit handles all of the serialisation and deserialisation for you, through the magic of Jackson data binding, so we didn’t have to think about any of that while we did the hackathon. We just wrote the thing on the right, and got the thing on the left for free.

The Symphony Java Toolkit also handled the presentation of the story on Symphony for us too. In kind of a basic way, although as we’ll see, this is customisable with templates.

So we haven’t set the story points yet.

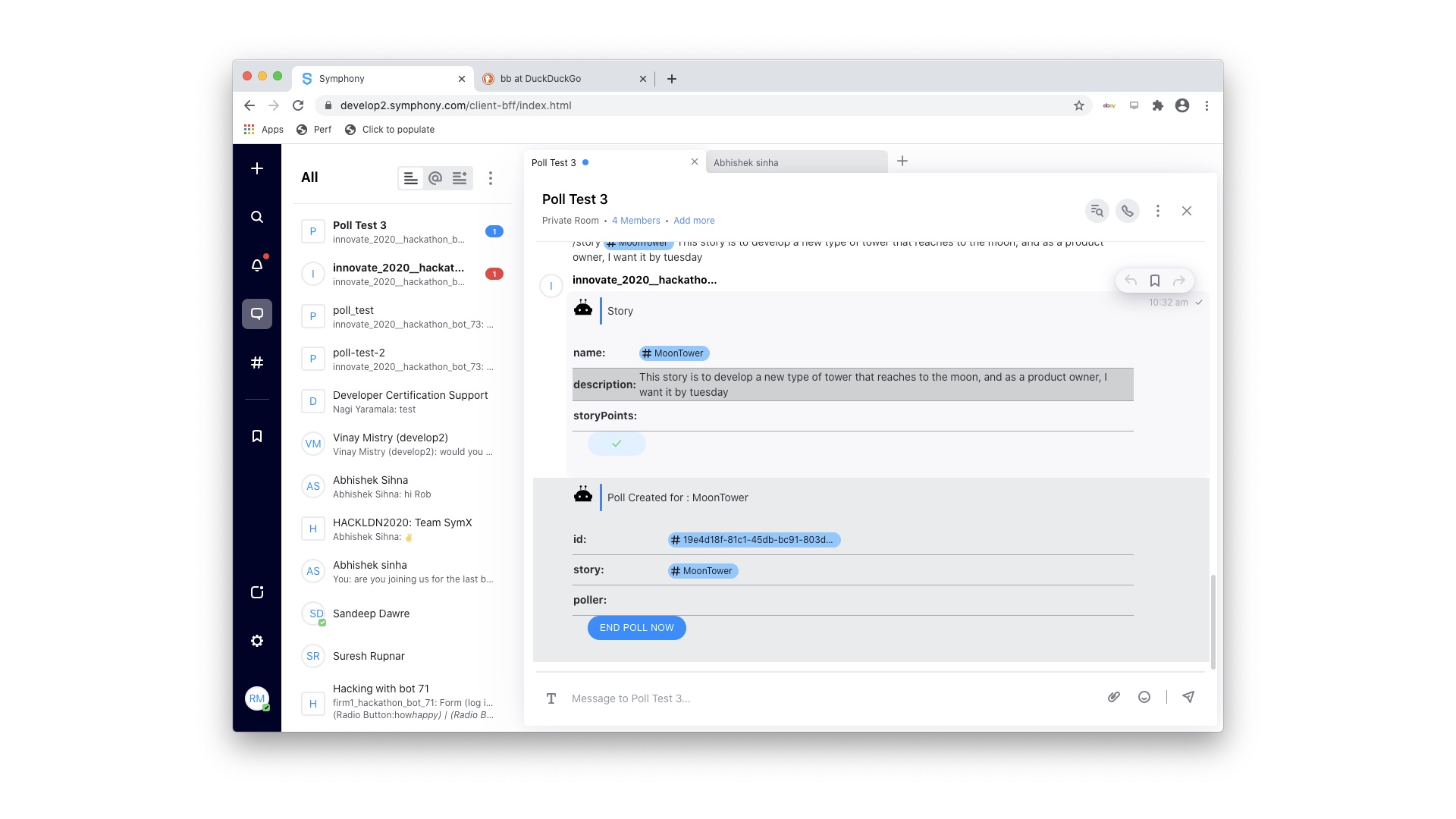

Next, if I click on that “Poker” button, which turned into a tick after I pressed it, our Symphony bot replies back: “Poll Created for MoonTower”.

And, as you can see on the top left there, I’ve been notified of a private message from the bot.

And, this is my private message here - asking me how many points I want to give to this poker story. So, this is the equivalent of playing that card in the real planning poker game.

And, Scrum uses these weird Fibonacci series numbers which I can’t quite get behind, but whatever. This is just a hackathon we’re not trying to reinvent the world here.

So, everyone in the original room gets a message like this, and they all reply back with their votes.

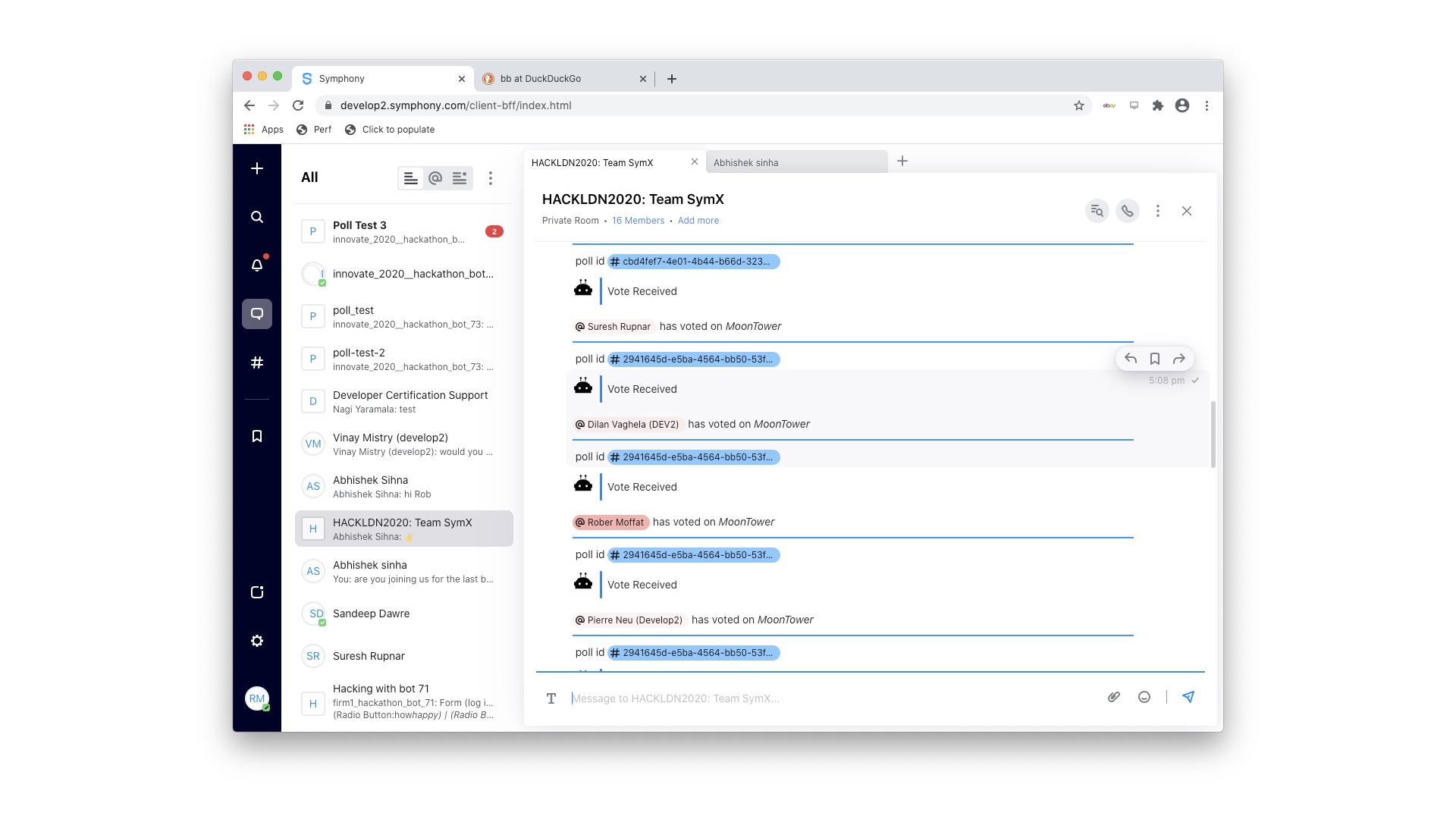

And, we did this live in the hackathon, and got all the judges to be in the room and start voting on the story too, so you can see them all voting here. You can’t tell how many points they gave, but you know they voted.

So, that was a really nice, interactive experience for everyone.

Behind the scenes, what’s happening? In the room, we are basically writing these votes as messages into the room. So, again, append only database - we are appending each Answer into the room.

Here we see the Java Bean code for the answer, and the JSON representation for it. We’ve got, the user, the pollId, the choice they made, when they made it, and so on.

Now, so that we didn’t show how many points the user gave, we customised the message view with a FreeMarker template. And, you can see that here at the bottom. It’s referenced in the Answer Java class, using an annotation.

And the Symphony Java Toolkit takes care of all of this for you. Super, super easy to set up. Also, The Symphony Java Toolkit basically generates and dumps out these FreeMarker templates if you don’t provide them. So you can take the default one that the toolkit creates, and customise it, and then reference it in your project.

So, you don’t really need to know how to code FreeMarker all that well, you can just play around with what’s there.

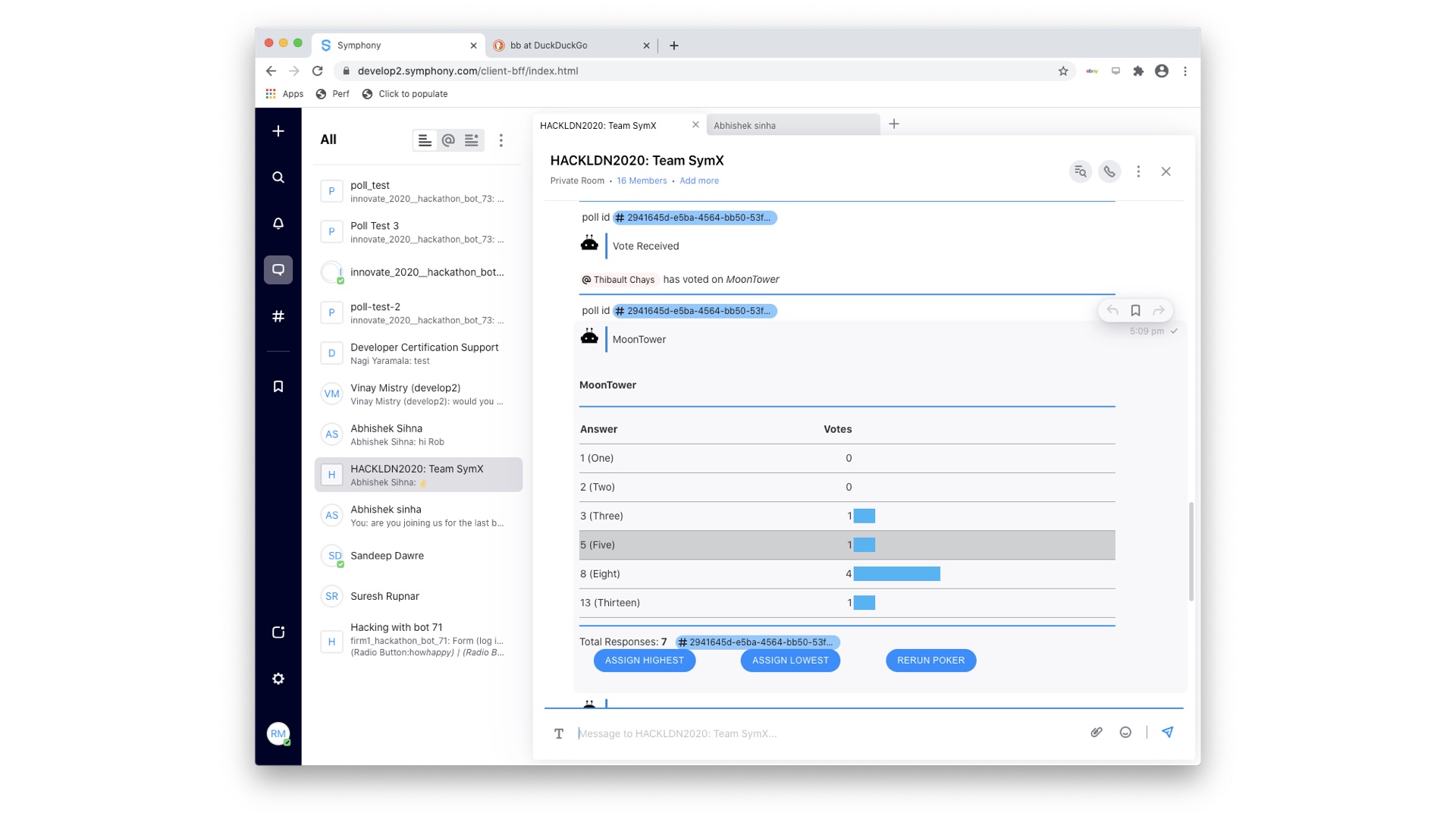

So, at some point, you decide everyone’s voted, which we left as manual in our hackathon, and you can close the poll by hitting the “End Poll” button.

And, the bot then looks back at all the Answers in the chat room, and tallies them up. It’s just like it’s doing a database query.

And again, using the FreeMarker templates, and the JSON, we produce this table of the results.

At this point, because all the results are different, in Scrum, you’d normally have a discussion about why they’re different, and then vote again.

And obviously, all of that can just happen in the chat room, with messages, or you could fire up a conference call in Symphony.

Once you get some kind of agreement, you can hit the “Assign” button, and set the results. We were really running out of time at this point, so we kind of fudged it: really, I think there should be a button to assign the most popular answer here too.

So I hit the button to assign.

And now, we’ve written a new message into the room, with the details of the story, and the number of story points.

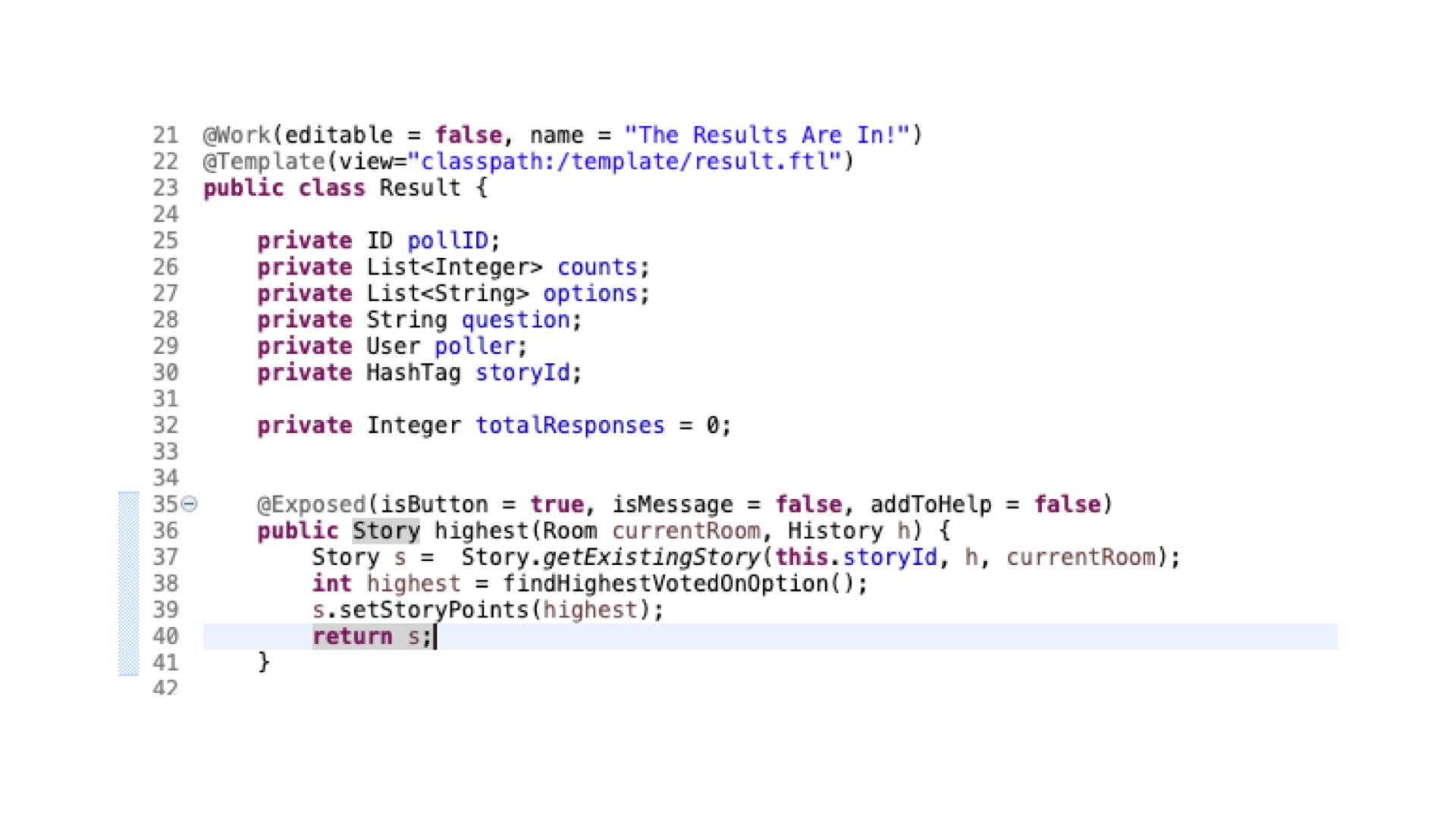

And, I’ll just show you one tiny bit of code to demonstrate how that function works.

This is our Result class in java. It’s got all the details as fields that it needs to display that bar chart of who voted for what: like the counts, and the names of the options and the question, and the Story hash-tag.

When you hit that “highest” button, what happens?

Well, it runs the “highest” method here, which gets passed some parameters. Symphony Java Toolkit will hand you pretty much whatever parameters you ask for, here, it’s very open, and extensible. So we can pass it the details of the room where all this is happening, for instance, and this History api too.

On line 37, we find the relevant story, and then on lines 38 we’re really trying to figure out what the highest result was, from the votes.

On line 39, we’re changing the Story object itself, and on line 40, we’re returning that new version of the story, which Symphony will put back in the chat room.

So, as far as our bot is concerned, we don’t really need to know much about messages, and chat rooms, and we can let the toolkit worry about JSON formats and things - it’s all taken care of.

This is a super simple way of building bots really, really quickly.

You write some simple Java bean class, and you can manipulate it in Symphony very easily.

And because it’s Java, we’re not stopping you talking to back end services… we could write some connector to fire these numbers back into JIRA or whatever tracking system we want. And, there are some bots to provide JIRA interop in Symphony.

So, this Hackathon bot was just a bit of fun: we’re going to show some people internally this, and see if they want us to carry on developing it. But personally, I’m not sure if Scrum’s Planning Poker is going to survive the transition to the post-agile COVID world.

But hopefully, I’ve used that to demonstrate some of the power of the Symphony Java Toolkit. There’s actually a lot more going on here that I haven’t covered. It does Symphony Apps, handles clustering for bots, handles micro service configuration, does FIX messages, can report on Maven Builds, provides heath endpoints and Spring Actuator metrics, it handles token lifecycle and so on.

And there are tutorials in there for all of these things.

We’re very proud to have been able to contribute this to FINOS, because we think that this is something lots of developers can benefit from. And, we’re currently talking to Symphony themselves. They’ve agreed to donate their bot toolkit development efforts to FINOS too, and work with us to combine our efforts. This is something for 2021.

So, watch this space, there’s certainly a lot going on in the world of Symphony bots, and we actually have lots more pieces of this in the pipeline, which maybe I’ll come back and talk about another time.

Thank you! Questions?

Made with Keynote Extractor.