1. All Work Is Risk Management

All Work Is Risk Management

Presentation about the origins and justification for Risk-First

So today I am going to defend this statement: “All Work is Risk Management”. And, this is one of the founding philosophies of Risk-First.

For the next 10, 15 minutes or so, I am going to try and persuade you that this is the case.

And while I’m making that case, maybe you can try and think up some counter-examples: bits of work that aren’t risk management, and then we can discuss them.

So, my approach to this is in three steps:

- first, I am going to make an appeal to authority

- then I’m going to talk about how the UK as a whole is doing risk management, t

- then I’ll bring it back to talk about the tickets on your backlog, and how they are actually just risk management in disguise.

A lot of people think Risk Management is really boring, or really technical. I want to get you away from that thinking. After all, if all work is risk management, then we’re doing it anyway, and it can’t be that technical.

Sure-you can make it really complicated with models and things, which is what I spent a lot of time building in banks. But actually, that is a special case.

I want to make the claim that you’re already doing Risk Management, and if you��’re good at your job, you’re probably quite good at Risk Management too.

So, I’ve worked in finance for many years. I’ve built systems for managing risk in banks, just like many of you have probably worked on systems for managing risk at your company.

So, me saying “All Work is Risk Management” is perhaps just a case of “seeing every problem as a nail”. This is a quote from Abraham Maslow, who was an early researcher in Organisational Behaviour.

I work in Risk! Am I just blind to everything else going on out there! If I made suits, would I say, “All Work is joining stuff together”.

Actually, that might work.

But no. It turns out I’m not the only person who’s said something like this:

The quote above is actually the first sentence from Chapter One of a fairly famous book on Software Development, written in 2000.

Does anyone know which one? Don’t worry I am about to tell you.

It's this one: Extreme Programming Explained by Kent Beck.

This is the first book on Agile I read.

And it seemed like a breath of fresh air compared with what I’d learnt at university about software development, which was all, Rational, Waterfalls, Iterative Development, Structured Programming, and so on.

Kent Beck had a bunch of ideas in “Extreme Programming”, that really deviated from the accepted “norms” of software development, like Pair Programming.

This is a picture of some guys Pair Programming.

Some people love it. A lot of developers grew to hate Extreme Programming because of this. They didn’t want to share a keyboard and mouse with someone, and work together.

But what is the point of Pair Programming?

What Kent is trying to avoid by recommending this is Key Person Risk. That is, having individuals on a team who are the only people who know about a thing.

And if they leave or go on holiday, your project is exposed.

That’s the idea, anyway: Pair Programming is a risk-management technique. Specifically, trying to address Key Person Risk.

Kent Beck also co-invented JUnit, which is a library for building Unit Tests. As a Java developer, I use this all the time.

If you’re used to Ruby, you’ll probably be familiar with MiniTest::Unit or Jest if you’re a Javascript programmer. They are basically just versions of JUnit for those different languages.

I actually can't imagine coding now without building tests as I go, and having tools to at least understand my coverage. It just seems so helpful now to have this.

Now, why do we write tests? Why are Unit tests such an integral part of Extreme Programming, and therefore Agile?

I would say, they are managing risk.

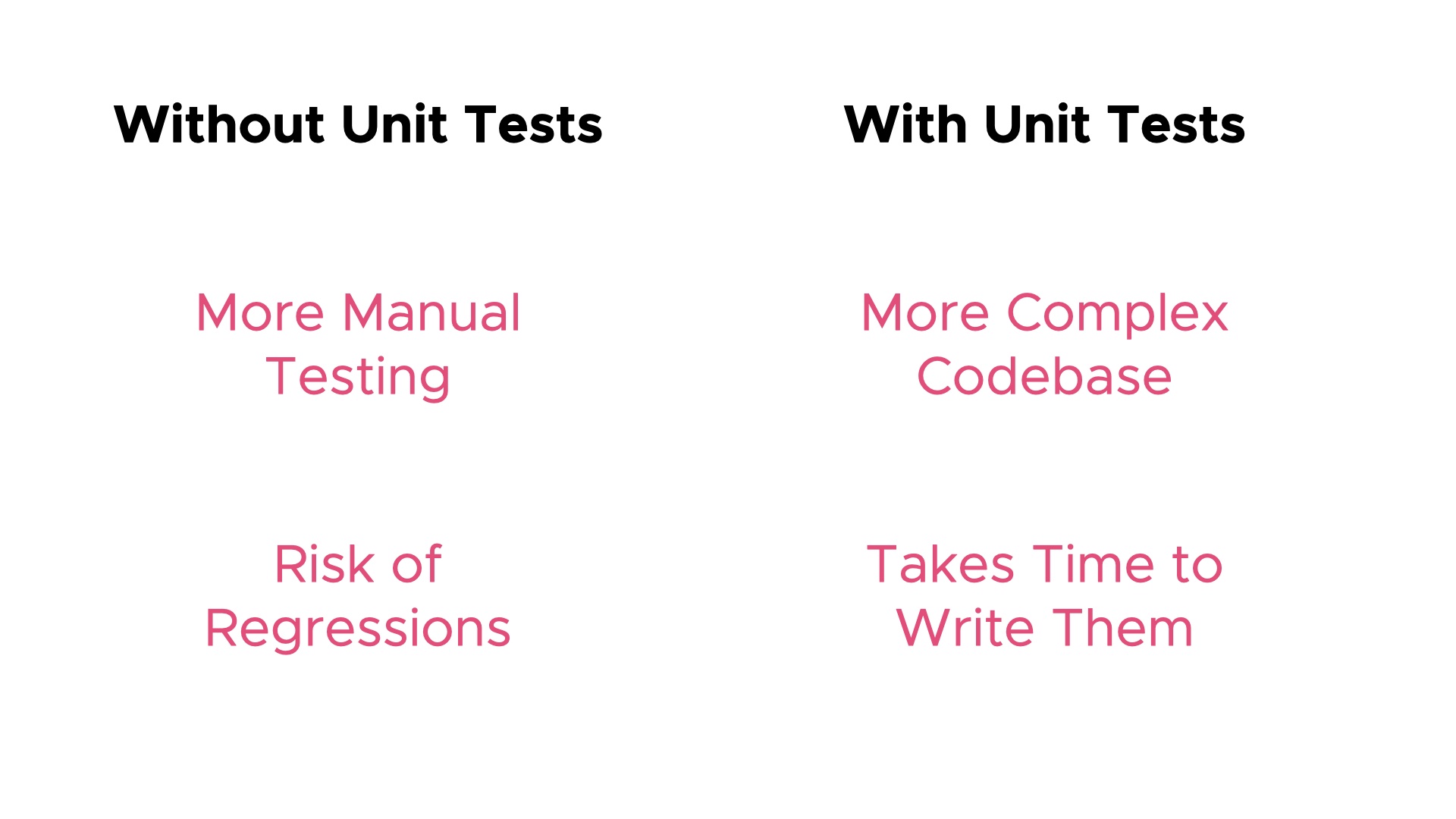

So, what risks is Unit Testing managing?

Well, it’s managing a couple of risks: Unit Tests are Automated, so they can be run all the time. This reduces the amount of Manual Testing you need to do. Too much manual testing is a risk, because well, it takes time and the feedback is slow, but also you have to rely on people to do it the same every time. And if people are bad at one thing, it’s doing the same repetitive task day-in-day-out exactly the same every time.

But also, there is the threat of regression: our code is going to change in the future. Are we going to break the functionality of our existing code when we change it? By having unit tests, we have some more certainty that when we do change it, we haven’t broken features and functionality that already exist.

So, the Risks we are managing with Unit Testing are on the left of this diagram. What’s the downside of Unit Testing? That’s on the right:

In order to address the risks on the left, I have to own some extra code in my codebase. So, that’s a complexity risk. The codebase is more complex.

And building those tests, and maintaining them, that’s going to take some of my schedule up, so there’s a risk to the schedule in writing tests.

Now, if you’re good at Unit Testing, this is a great deal. What I mean by “good deal” is that the benefit -the upside- outweighs the cost -the downside.

The trick is to write just enough tests to address the risks on the left. But if you go crazy, you end up turning it into an industry, which blows up those risks on the right.

So, Unit Testing is a trade off. Being good at Unit Testing means being good at controlling the risks on both sides of this slide.

And, so this slide gives you a clue as to what Risk-First is about: it’s about exploring and categorising the risks that affect software projects, and pointing out these trade-offs.

Ok, so let’s move on from Extreme Programming for a minute.

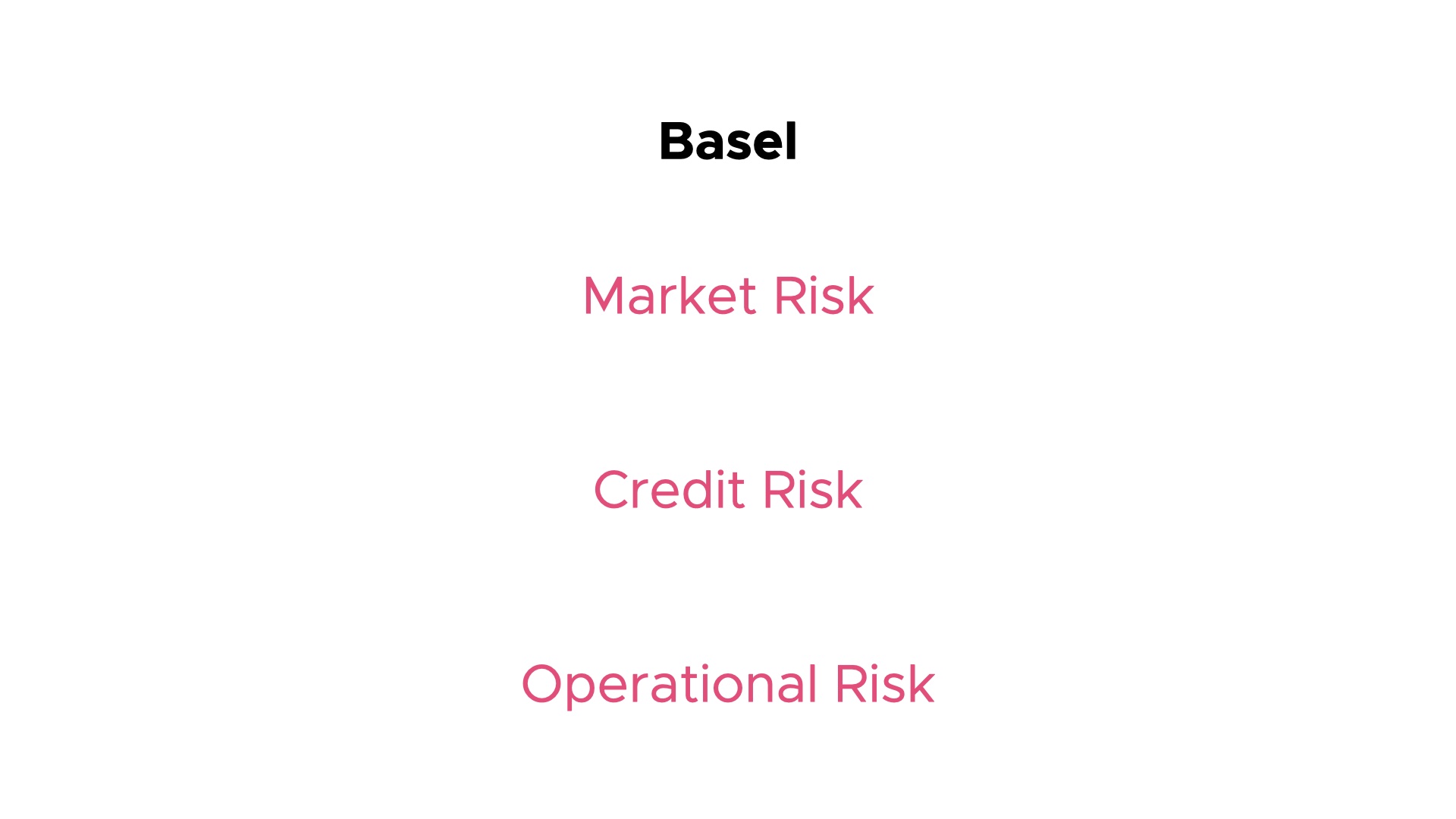

My background is in the finance industry. When I worked at RBS and Credit Suisse, I was working on finance regulations. One of the most famous ones is the Basel Accord. I worked on version 2 of the Basel regs, but we’re about to hit version 4 now.

So, amongst other things, it defined three types of banking risk, and demands that banks measure and report them.

Market risk is the risk that financial products you own, like say, foreign currency, will change in value. So, if you bought some dollars wanting to go on holiday, and the exchange rate changes, then the dollars might be worth less by the time you actually go.

And Credit Risk is the risk that people who owe you money, won’t pay it. And, I think we can all see that certain people or companies are going to be more reliable at paying their bills than others.

Finally, Operational Risks are things that affect the operation of your business. Things like, software systems going down, data being lost, numbers not adding up. Working in insurance, I expect you’ll be familiar with this term. This is all about the banks not working and losing money due to human mistakes or just bugs in the code.

A good way to think about Operational Risk is to think about the whole firm as a machine. Operational Risks are ways in which the machine can break. They can result in financial losses, or maybe reputational damage.

So what things like the Basel Accord did, was force banks to start seriously measuring and reporting in terms of - what are the risks to our business, and how are we managing them?

And they were able to do a “divide and conquer” approach: different departments dealt with the different risks.

So, banks do Risk Management seriously now. But also, this is done at a national level: even the UK government is talking about Risk Management!

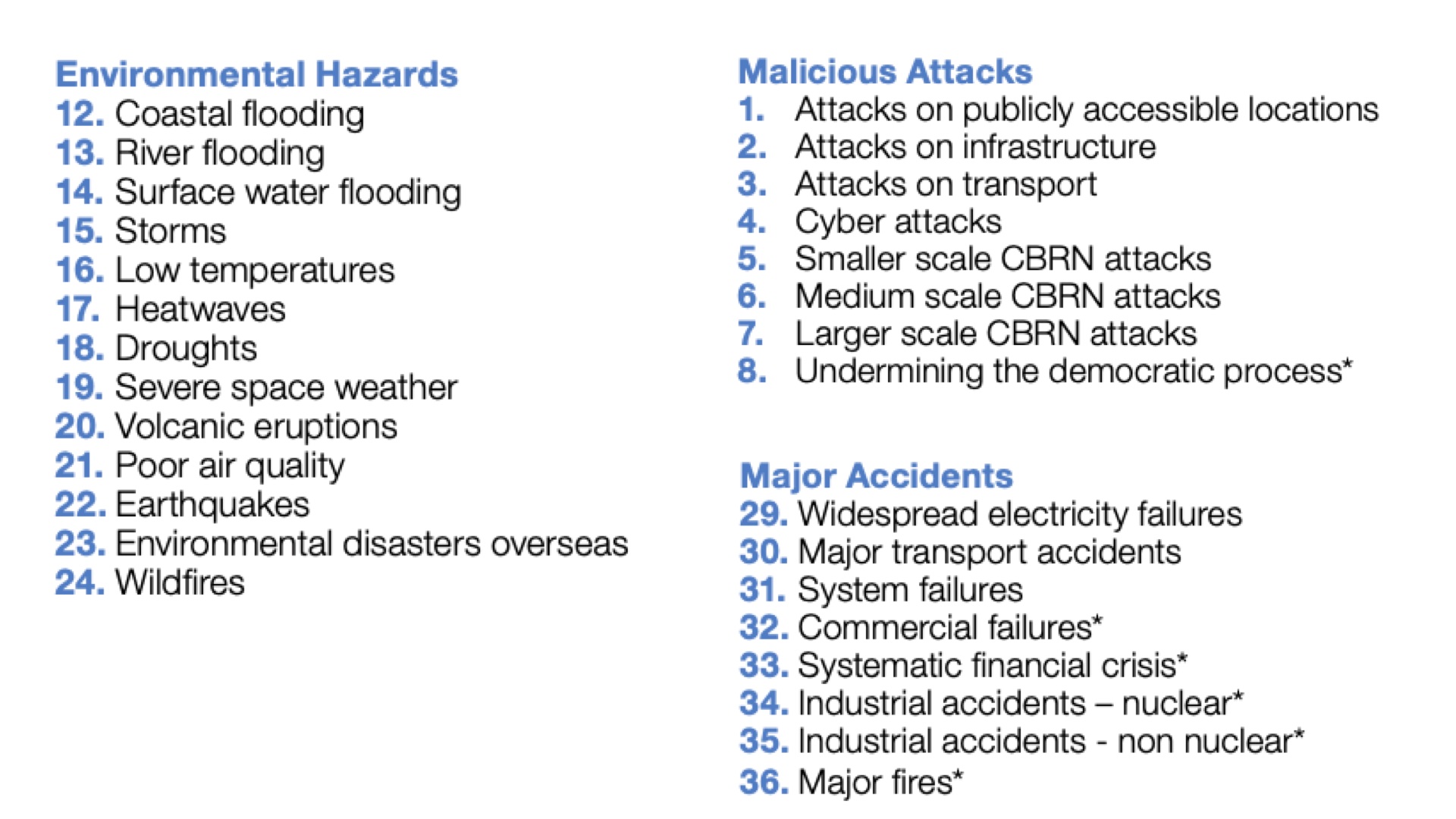

This is the cover of the 2020 UK National Risk Register. So, what things do you think the UK government worries about?

So, here are a few of the risks from the National Risk Register. I’m not going through all these, but it’s all the kind of disasters you’d expect.

Storms, Heatwaves, Cyber Attacks.

CBRN is Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear, by the way.

And they have a go at estimating both the likelihood of these risks, and the cost. Where the cost is not just in financial terms, but also in lives.

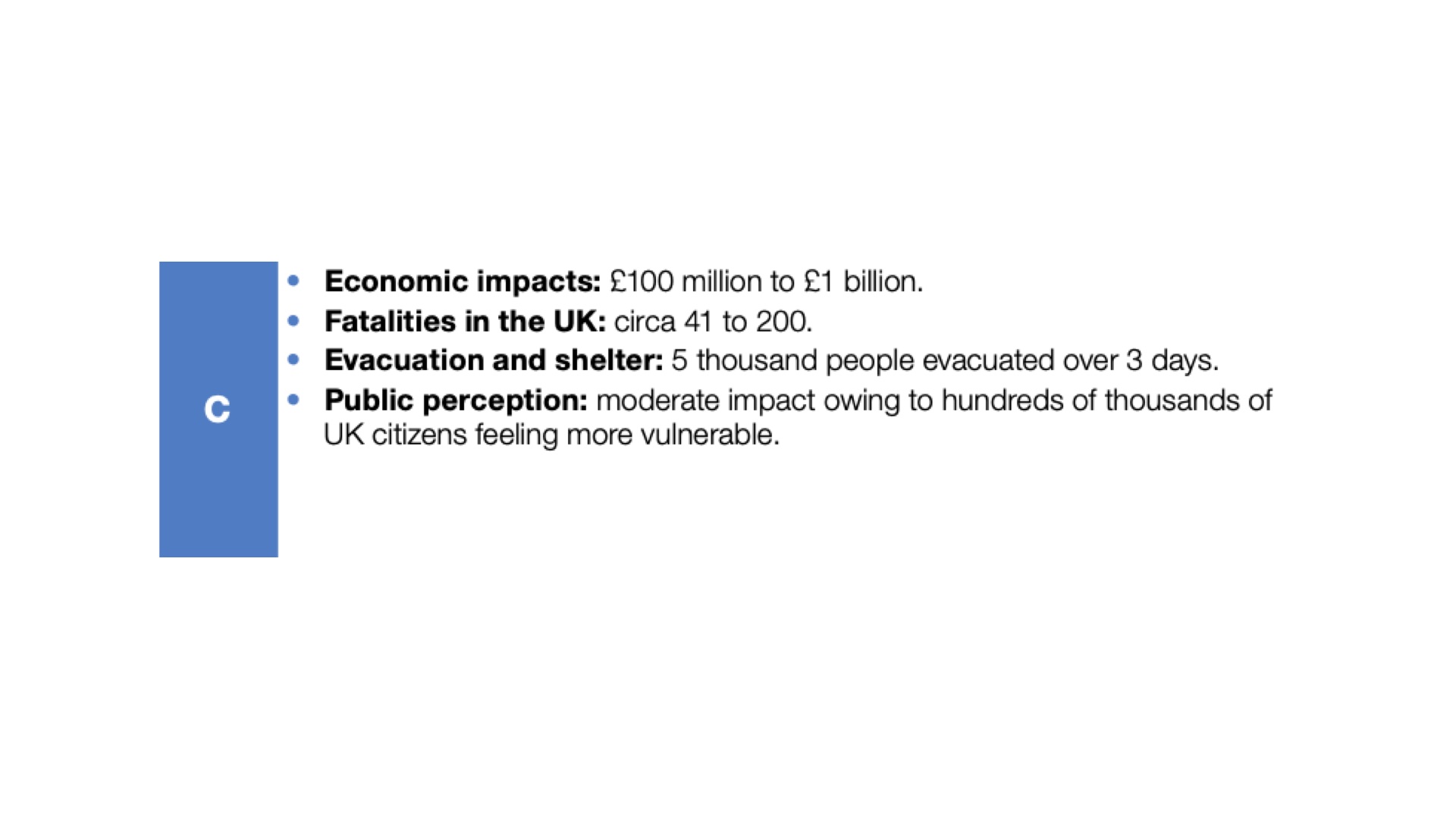

For example, Major Fires, number 36. In the report this is given a probability of 5-25 in 500 chance of happening each year.

And it’s categorised as impact level C, which.. you can see here means up to 200 fatalities and possibly up to 1 billion pounds cost.

So, just like the Banking Regulations are trying to address risks to banks, the UK government are applying Risk Management to the country as a whole.

The body of this report is trying to answer the question: what are we doing about these risks? What can we do to limit the damage they cause?

So, my thinking is: can’t we do the same thing for software projects? Just as the UK government and banking apply a divide-and-conquer approach to managing risks, can we do the same?

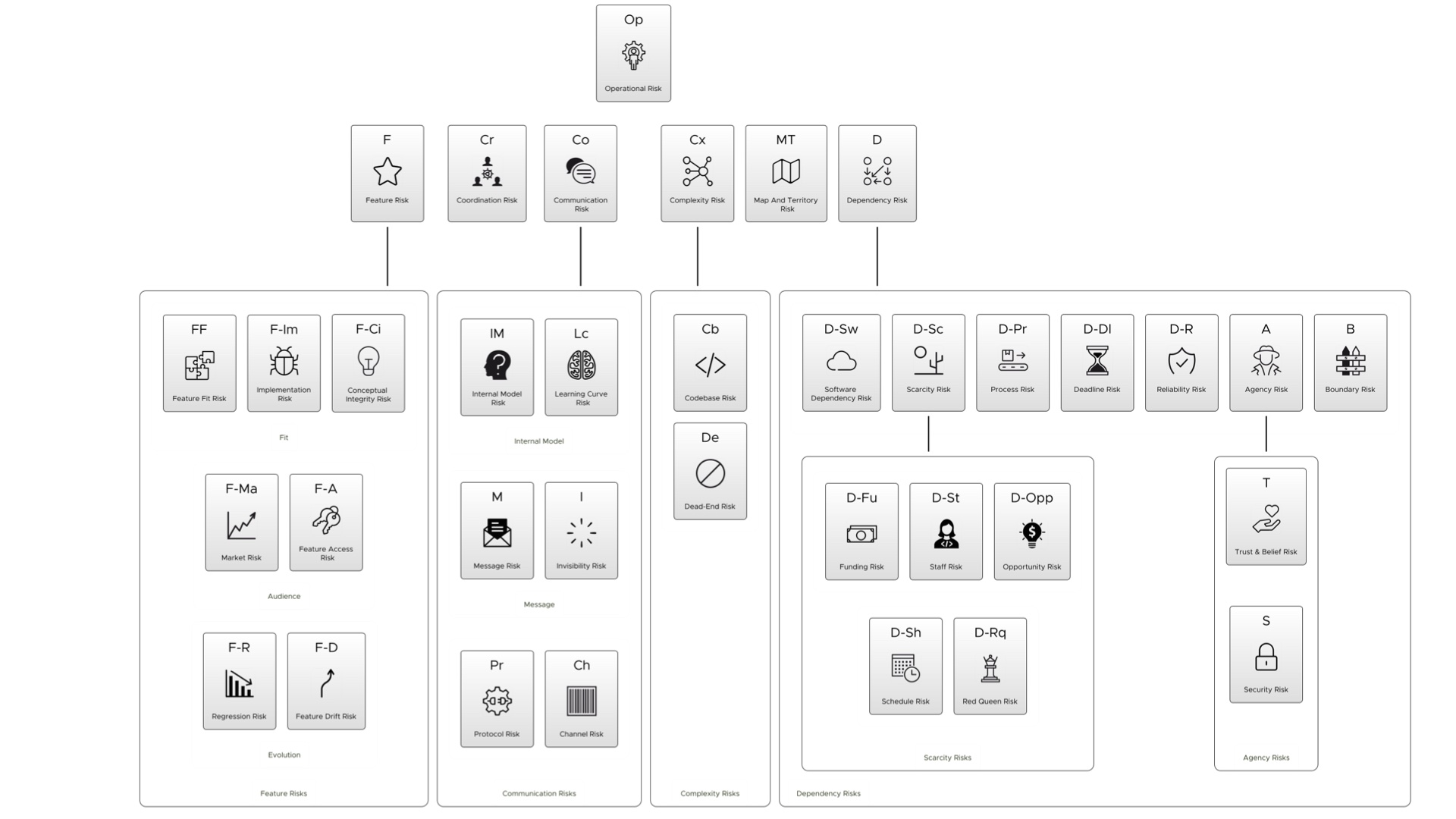

So, I set about breaking down the various risks we face on software projects. I’ve got a few of them on this slide here.

So, first up: communication risk. We see this risk between people and between systems- important messages go missing, or are misunderstood, things like that.

Complexity Risk: The more code we own, the more complex the systems we build, the more likely they are to go wrong, or contain bugs. That’s true of software systems, and processes involving people.

Coordination Risk: So, when you’ve got a lot of people working together, how do you coordinate them so that they don’t step on each other’s toes? Like, maybe two sets of people working on the same file at the same time. Or the same problem at the same time, but separately. We face this problem with our systems too, when we have multiple processes trying to write to the same file, say.

And Operational Risk: we’ve already talked about that with banks, but it’s a really important problem for all IT. Like, what if the servers go down and your website is down for a day? Or maybe a form on your website is broken and people can’t sign up? Even people being ill and off work might turn into Operational Risks. How do we catch these and fix them quickly?

There are more than just four of these, and we’ll see some more as we go.

In the book and on the website, there’s a chapter on each, and what you can do to address them.

So, big question: is that useful?

What I’m creating here is a “pattern language” to talk about the problems we face on Software Projects.

In a way, all of the risks in the UK Government Risk register are also patterns. Patterns are really the way we are able to talk about stuff.

The first time I was introduced to the idea of patterns was in this book, Design Patterns Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, which showed you a load of reusable patterns that you could employ to make your software more extensible.

This was a huge influence in the software world.

Things like “The Decorator Pattern” or the “Abstract Factory” come straight out of this book. Many of you will probably be familiar with those.

If you’ve not heard of design patterns, then here’s another pattern language. TVTropes is a website that talks about patterns in narrative.

Here’s a pattern called “Or Was It a Dream”. I think everyone is familiar with this tired old trope in TV programmes. Oh, it was a dream… or was it!

This is a really cool site though - it’s well worth a look. There are some completely obsessive people keeping this up-to-date.

Ok, so at this point, I’ve made the case that some of the practices in Extreme Programming are about managing risk. And, I’ve talked about the idea of Risk Management in Banking, the UK and in software development.

But, I’ve not really delivered on this original slide’s idea that “All Work is Risk Management”.

But, I’m ready to give it a go now. So…

Let’s say this piece of text above is a task in your backlog. Or, a JIRA item. Or a GitHub issue. Or whatever you use to track these things.

Let’s break it down in terms of risk.

“Debbie needs to visit the client to get them to choose the logo to use on the product, otherwise we can’t size the screen areas exactly.”

What are the risks here?

So, first, we can see there is a Dependency: doing one thing depends on something else. Sizing the screen can’t be done until we have the logo.

Second, there’s a Coordination Risk here. Who does Debbie need to see? How easy will it be to get them both together? Are they going to have a profitable meeting, and come to a conclusion. Or not.

Third, there’s a staff risk: Who the hell is Debbie? Why does it have to be her? What if she’s sick, or leaves the company or something. A Staff Risk is also a kind of dependency risk - but a dependency on someone, rather than say a piece of software or a server or something.

Finally, and perhaps this is implicit, but if you can’t size the screen areas, does that hold up the whole product? Are we going to have issues delivering to clients what they want, when they want it? In Risk-First terms, this is a Feature Risk: the risk of features that the clients want not being available, or the features that are available, not being valued by the clients.

So, I can break down an item of work, and look at the risks it is addressing, and how it addresses them.

Now the thing is, at some level we do consider all these risks when we are working on a project, but it tends to be more implicit.

So, here’s a GitHub project that I’m working on at the moment. It’s basically a Kanban-type board, although you might be more familiar with backlogs or scrums. Essentially, when we choose what to work on, we are doing Risk Management.

We either pick the tasks which will “knock out” the biggest risk, like maybe fixing security breaches or investigating crashes, or, we pick tasks that give us the most “bang for buck”. That is, like good unit testing, where you’re reducing the overall level of risk on the project.

So, just looking at this list above, I can see a few items to do with testing there: they’re improving the quality of this project - hopefully reducing those operational risks that we talked about.

There’s a few to do with making sure we have the right features - so that’s addressing Feature Risks: we want people who use this to find the functionality they need.

There’s a tutorial over here. Hopefully, that’s addressing a Communication Risk, making sure people understand the project and can use it.

Now, at this point, you might be thinking - how many of these risks are there? tvtropes has literally thousands of different tropes recorded. Is it the same for Software Projects?

Luckily, the answer is no. On the Risk-First website I just break it down into about 50, and some of those are just more specific versions of others. There are many different types of Dependency Risk - such as Agency Risk, and Reliability Risk.

I run through these on the website but we’re not going to go into detail today.

So, this classification is about the same sort of size as the UK national risk register.

Ok, so, a good question now is: does this help?

Does thinking about what we have to do in terms of risk make it easier to “do the right thing” in software development?

This is a big question that I am going to answer really over the entire rest of this talk.

So Nassim Taleb, who wrote the black swan said this. We’re good at risk management.

200,000 years ago those risks might have been: what if a wolf comes and eats our sheep? Ok, well a good risk-management strategy might be to have a shepherd. A shepherd is risk management.

What if we have a particularly long winter? Ok, well we should store grain in a silo, or pickle things, or store apples somewhere. Storing food is risk management. In fact, agriculture generally is risk management: it’s managing the risk of not just finding the food lying around when you need it.

The risks were different back then, but it was a case of preparing for whatever was going to bite you. Sometimes, literally.

There are lots of things our brains are bad at. We’re not good with probability, which, we’ll look at later. We’ve got this weird, random dopamine reward system which means we get addicted to gambling and social media. We’re not perfect.

But, we’re good enough at this: this is one of our skills. Without realising it, we put it to work when we build software. We’re always thinking: what if the user does this? What if this thing stops working? What about this single point of failure?

When we build good software, it’s because we’ve done good risk management.

So, is All Work Risk Management?

Is this correct? Maybe you’re not convinced. I don’t know - perhaps check out riskfirst.org if you need a bit more convincing.

Thanks for watching - hit like and subscribe if you want more

Made with Keynote Extractor.