Crystals And Code

In this article, we're going to look at how Information Systems (IS's) are like Crystals: strong, rigid efficient, but prone to defects and flaws.

IS's are super-useful for hardening and regularising processes so that they follow standards, run more quickly, cheaply and smoothly and take expensive, error-prone humans out-of-the-loop. The downside is that IS's are fragile in the face of change. Just like a crystal they display strength and rigidity over flexibility.

Here, we're going to explore the shared (and somewhat idealized) life-cycles of crystals and IS's, and draw some conclusions along the way.

Stage 1: Chaos

Before crystals can grow, the conditions have to be right. In turbulent, changing environments, large crystals can't grow (just think of a slush machine, continually churning the drink to keep it from turning into a block of ice).

Slush Machines

The same is true of an IS - it's only once things settle down that patterns of behaviour appear and we can start to build abstractions to automate and control them. The more consistent and predictable a process is, the easier it will be to create a successful IS for it.

Most IS's start small, and grow from there (eBay started with a single niche market, Facebook started with just students at Harvard). They have to demonstrate usefulness at every scale.

What properties of IS's are like the regularity we see in crystals? How about things like:

- Managed Data, with clear, consistent, interacting data-types. In distributed systems, there will be a policy on CAP. There is likely to be a high degree of data Normalization and a well-Factored design.

- ACID properties, such as Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability of transactions.

- SLAs: Response times, ownership, procedures, and other non-functional requirements that are clearly defined.

- Support Teams and Knowledge Bases: there are procedures in place for understanding and using IS's.

- Roadmaps and Plans: development and growth are ordered and directed as opposed to chaotic and random.

When we see quotes like:

"etcd is a strongly consistent, distributed key-value store that provides a reliable way to store data that needs to be accessed by a distributed system or cluster of machines. It gracefully handles leader elections during network partitions and can tolerate machine failure, even in the leader node. " -Etcd Home Page, Etcd

We're talking about an example of a well-thought-through, consistent, carefully-designed IS, because it has opinions about all of those properties... as opposed to the wider organisation they exist in, where none of these things really exist.

Stage 2: Growth

Did you know that jet-engine blades are actually single crystals of metal?

Turbine Blade, From Wikipedia

Engineers at Pratt and Whitney perfected this technique because without it, the blades are prone to snapping, along the lines of Crystallographic defects.

However, in less controlled environments, crystals grow with defects baked into them, caused by smaller crystals merging together, or changing conditions perturbing their creation.

Garnet inclusion within a diamond - Wikipedia

IS's usually don't grow in isolation either: as they grow in complexity and usefulness, their responsibilities and coverage begin to overlap with each other and it eventually becomes important that data is shared between them. The problem is that because the systems have started in isolation, they contain different local conceptual hierarchies. The users of those systems also think in terms of these conceptual hierarchies. For example, one system might have the concept of "Client", whilst another has the concept of "Legal Entity". Are they the same? Probably not.

In the growth stage, users will be forced to "live with" the incompatibility of the two (or more) systems, and the knowledge that the data in each of them is different, there may be gaps, and potentially contradictions.

Stage 3: Competition

Many of the crystals we extract from the earth are flawed with defects, because of the way they have grown. In the same way, with IS's we have to make hard decisions about how to deal with these flaws:

Option 1: Live With Them

We could simply "live with" the differences between IS's. This means accepting different, contradictory views of reality, and usually a lot of copy-pasting of data from one system to the next.

Sometimes, this means hiring people who's job it is simply to reconcile the differences manually between large, incompatible IS's.

Option 2: Refactor

In Software Development, within a single code-base if we come across competing abstractions we can decide to refactor. An example of which might be identifying the competing abstractions used in different areas of a code-base, and merging the functionality of both, keeping just one "winner".

If you have type-checking and a decent suite of automated tests then refactoring can be pretty cheap. But how about refactoring an entire organisation?

This is not so easy. Making any mutative change on a large organisation can be unwieldy:

| Code Base | Whole Organisation |

|---|---|

| Type Checking / Compilation | Dry-Runs |

| Automated Test Cases | Small-Scale Roll-Outs |

| Test Environments | Only One Organisation |

| A Few Developers | Potentially thousands of users and clients |

The larger the scope of the change you're making the more risky refactoring becomes.

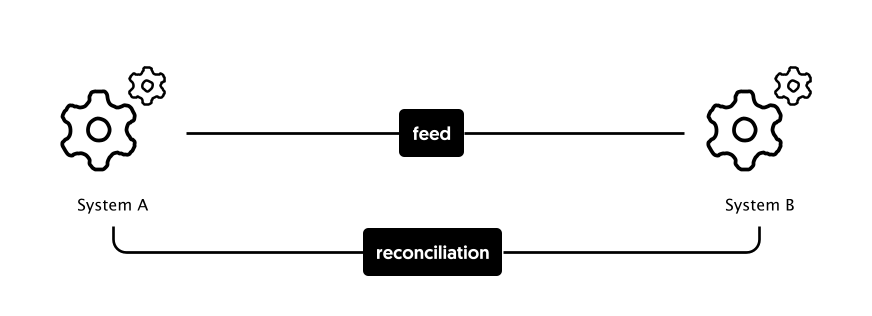

Option 3: Feeds & Golden Sources

Option 3 applies where you can't refactor to a single system. Instead, you can try and resolve the discontinuities by papering over them with automated feeds.

One of the IS's is designated the "Golden Source", or master. Any change that occurs in the world is recorded in that system. Those changes are fed to the other systems on some regular basis, perhaps using a message bus, or some kind of regular file-transfer.

There are four basic problems with this approach:

-

There is still no "Conceptual Integrity" between the two systems. The concept of "Legal Entity" and "Client" might have to be bent in each system in order for the data to flow. This might be resolved by having a "Legal Entity" record for each client, even though perhaps several clients belong to the same Legal Entity.

-

The information required by the two systems might differ. For example, one system might contain the client's addresses. The other might require information about legal agreements. If one system ends up feeding the other, then somehow, fields needed by the "downstream" system will need to be added to the "upstream" one, or, you have some situation where some fields are maintained in the downstream system, and some in the upstream system.

-

Reconciliation becomes a thing. Since you are effectively creating copies of the same information in multiple systems, you now need to check that all of the different copies are the same. This usually involves creating a fourth system, that checks the results and arbitrates on the other two.

So, you've gone from two incompatible systems to four points of failure: the two original systems, the feed, and the thing that checks the feed.

Stage 4: Destruction

Crystals can only exist when the conditions are right: everything has a life-span. Diamonds aren't forever, and IS's even less so, since the competitive landscape on which they exist is violently evolving all the time. How does an IS deal with change? There are two basic ways:

Growing The Crystal

Perhaps you can "grow" the IS (defects and all) in the direction required by the new functionality. This is great if the new functionality is somewhat adjacent to something it already does, but does nothing to fix any defects that are already established.

Seeding A New Crystal

This means setting up a new team somewhere who are allowed to "iterate rapidly" building something new without the weight of history and existing defects slowing them down. As in Stage 2, eventually, if this team are successful, there will be new defects to resolve, between the new and the old systems.

Defects in the crystalline structure are effectively another way to envisage Technical Debt.

Diamonds Aren't Forever

What are the take-aways from this article?

-

Order Is Expensive. Maintaining order within an IS is a battle against the Second Law Of Thermodynamics. i.e. Without perpetual vigilance everything turns to crap.

-

We're stuck with flawed IS's. Because of the way we build organisations, there will always be flaws along IS boundaries. The faster the rate of change, the worse this will be. Trying to construct a "flawless" organisation is going to prevent you from handling change in the future.

-

We need to manage the flaws. There are a few ways of dealing with the flaws - refactoring, living with them and feeds. But it's perhaps best not to strive for perfection because...

-

Destruction is just around the corner. Change is coming, and your IS will break when it does. So ill-matched, flawed IS's are here to stay. They're a natural consequence of the fact that we live in a world where consistency is expensive, and change is constant.

In the next article, we're going to look more closely at the towers of abstraction we use to build our crystal castles.